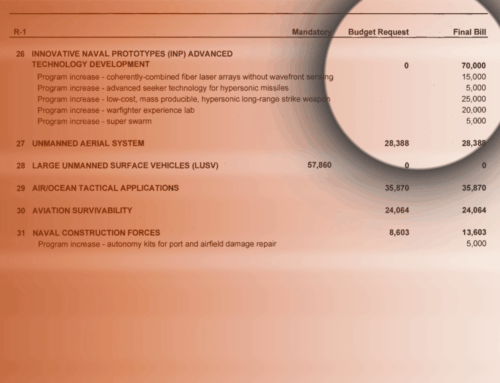

The House did something noteworthy last week. It passed three full-year FY2026 spending bills that look very little like the administration’s budget request.

These bills are not law yet. The Senate still has to act. But this is no longer just a committee marker. The House passed the measures with overwhelming bipartisan margins, which tells us something useful about where Congress appears willing to assert itself.

The package covers three of the twelve annual appropriations bills. One funds Interior and Environment, including most of the Department of the Interior, public lands agencies, EPA, and the National Park Service. Another funds Energy and Water, covering the Department of Energy, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Reclamation, and federal water and power infrastructure. The third funds Commerce, Justice, and Science, from economic data and weather forecasting to law enforcement, courts, and basic scientific research.

Across all three bills, House appropriators rejected the administration’s proposed deep cuts and substituted a more conventional spending plan. The differences are not subtle.

The Interior and Environment bill provides $38.6 billion in discretionary budget authority, about $9.5 billion—or roughly 33 percent—above the administration’s request. That level is below FY2024 enacted funding of about $41.3 billion and FY2025 enacted funding of about $43.4 billion, both of which were carried forward under a full-year continuing resolution. The Energy and Water bill provides $58.0 billion, more than $3.5 billion above the administration’s request and roughly in line with FY2024 and FY2025 enacted levels. Commerce, Justice, and Science comes in at $81.3 billion, roughly $17 billion—or about 26 percent—above what the White House proposed, but below FY2024 enacted funding of $83.5 billion and FY2025 enacted funding of $82.5 billion.

Those toplines are reinforced by specific programmatic choices. EPA would face a 4 percent cut, or about $320 million, rather than the more than $4 billion reduction proposed by the administration. The National Park Service would see a moderate reduction from current levels, not the 37 percent cut included in the White House request.

Congress didn’t just protect funding. It also redirected it. Trade agencies received notable increases, including an 18 percent boost for the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and a 23 percent increase for the Commerce Department office responsible for export controls aimed at China and other countries. The Justice Department Inspector General was funded at $139 million, roughly 43 percent above the administration’s request—an unmistakable signal about oversight priorities.

Taken together, this is not a spending spree. It is a refusal to implement the administration’s budget as written. That distinction matters in the current context. Over the past year, appropriations have increasingly been treated as provisional. Funds approved by Congress have been delayed or slow-walked through impoundments. Obligations have been pushed past the point where programs can operate as intended. Rescissions have been proposed long after spending decisions were made, sometimes structured to expire if Congress does not act, effectively daring lawmakers to intervene or accept cuts by default.

Seen in that light, these bills look less like generosity and more like self-defense. When appropriators specify funding levels program by program and reject sweeping reductions, they limit how much room exists for quiet rewrites later.

The hardest tests are still ahead. Defense and Labor-HHS-Education—nearly 70 percent of discretionary spending—remain unresolved. And even if Congress finishes the job, it will still have to enforce it. Appropriations only matter if Congress is willing to respond when they are ignored.

For now, this package is best read as a signal. Congress is reminding the executive branch—and itself—that writing the check is not a suggestion. Whether that reminder sticks will be one of the real tests of 2026.