As wildfires rage in the West, Hurricane Sally dumps rain across the Southeastern U.S., and drought grows in much of the country, disaster preparation – and relief spending – is once again in the spotlight. While the coronavirus is an extraordinary event that has led to an extraordinary response, we sadly know natural disasters will occur and climate change means they are going to be more intense. The country needs to better prepare, mitigate, adapt, and pre-spond to future disasters. That means tough public policy choices to disincentivize bad private decisions. Response funding should reduce future impacts from similar disasters.

To be clear, there is a legitimate federal role in responding when events exceed any single state’s ability to deal with natural disasters and emergencies. But that also means that states need to help themselves – and federal taxpayers – out by mitigating risk through better planning and building decisions.

One response area that has improved in recent years is budgeting for disaster. The Budget Control Act of 2011 ushered in an important reform. For years lawmakers low-balled the Disaster Relief Fund budget – the account used to immediately respond to disaster – knowing that emergency funding would come quickly after disaster struck. The BCA swept away this bit of budgeting fiction by requiring the DRF to be funded annually at the amount of the average of disaster spending over the previous ten years (high and low years thrown out leaving eight). Not exact, but a good proxy and excess funding in any given year would be there for future years. Starting in Fiscal Year 2020 wildfire funding got a similar treatment with an additional more than $2 billion available if costs exceeded the $1 billion provided for it annually. Previously, the Forest Service would raid other accounts intended for wildfire mitigation.

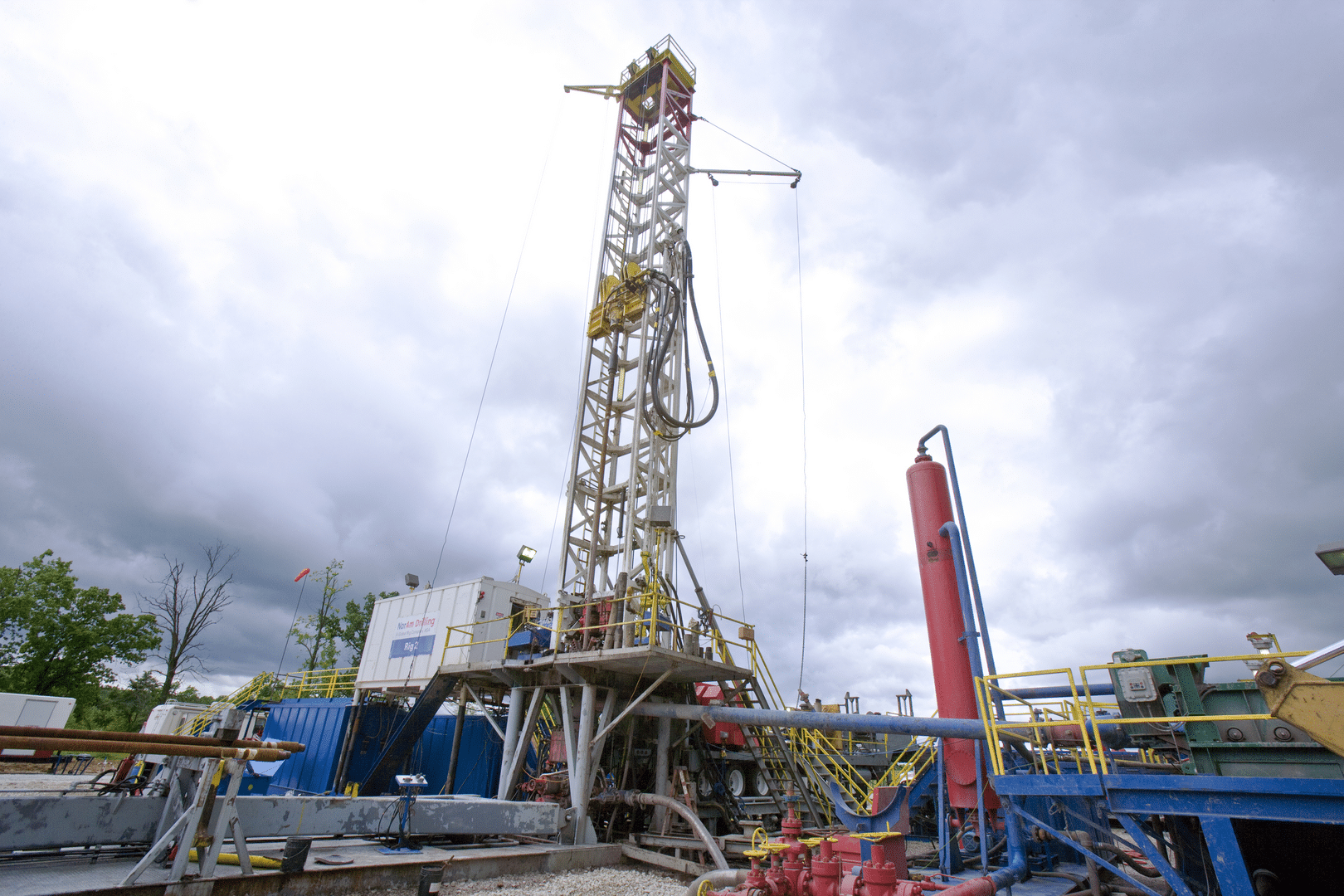

While the President rails against the state for California wildfires, he should look in the mirror. The fact is the majority of forest land in California (and other western states) is federal. And not surprisingly the majority of acres burned is federal. But funding for projects that mitigate such as invasive species programs and watershed restoration have been raided for years. In addition, federal aid should work in concert with state and local programs to mitigate fire risk at the local level including better zoning and fireproofing measures and assistance to people to relocate.

On the other side of the spectrum is the existing ag safety net, which seems to expand without strings attached. Of the many federal subsidies for the agriculture sector, the federal crop insurance program is the most expensive and was established to prevent the instability and unpredictability of relying on annual ad-hoc assistance from Congress when disaster strikes. Okay, we have our criticisms and it could be better structured, but okay. But then the small number of irresponsible farmers that chose to not buy federally subsidized crop insurance were rewarded when Congress appropriated $5.4 billion in ad-hoc assistance for ag losses from natural disasters in 2017, 2018, and 2019. This despite the vast majority of acreage in the areas affected by the disasters being covered by crop insurance. It would be ridiculous for casinos to reward gamblers for making a bad bet. We cannot reward farmers and ranchers for making a bad bet by not purchasing crop insurance, especially for a program that historically pays out. Not to worry, for farm businesses that did have crop insurance, USDA delivered “top up” payments in addition. And there are increased calls for assistance to farmers and ranchers affected by the derecho in Iowa, where 90 percent of their corn and soybean acres are insured.

Amid all this, there isn’t enough mitigation funding to prevent the predictable when communities are encouraged to farm or build where they shouldn’t. We know that for every dollar spent, mitigation saves six dollars or more on disaster response. And yet, this short-sightedness on a federal level is as true for picturesque fire traps in California canyons as it is for flood plains in Florida. Federal policies need to disincentivize behaviors that essentially create manmade disasters and stop over-insulating people and communities from the risks they face. Especially with climate change intensifying and extending weather events – the 2020 hurricane season already has only one name left on the list before it turns to the Greek alphabet, even though we’re only halfway through the season.

Congress currently finds itself in the unenviable position of needing to separate legitimate unmet needs from cynical subsidy seekers in any future emergency disaster spending bill. We’re sympathetic, to a point. Because, we’ll say it again, Congress needs to roll up its sleeves and do the hard work. Make the tough decisions, think ahead, budget properly, and mitigate risk so that we’re not always responding to a predictably bad outcome. Anything less is fiscally irresponsible and, as the headlines have shown in bold face this summer, immeasurably devastating to the people living out the consequences.