New York Times bestselling author Michael Grunwald joins host Steve Ellis to discuss his forthcoming book “We Are Eating the Earth: the Race to Fix Our Food System and Save Our Climate,” coming out July 1st. This episode reveals how agricultural lobbying has created a web of costly policies that benefit agribusiness while exacerbating climate problems. From the biofuels boondoggle that eats up a Texas-sized chunk of farmland to the “faith-based conservation” programs burning through billions in taxpayer dollars, discover why so many “green” agriculture solutions are climate disasters in disguise.

Transcript

Announcer:

Welcome to Budget Watchdog All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget spending and tax issues facing the nation. Cut through the partisan rhetoric and talking points for the facts about what’s being talked about, bandied about and pushed to Washington, brought to you by taxpayers for common sense. And now the host of Budget Watchdog AF TCS President Steve Ellis.

Steve Ellis:

Welcome to All American Taxpayers Seeking Common Sense. You’ve made it to the right place for 30 years. TCS that’s taxpayers for common sense has served as an independent nonpartisan budget watchdog group based in Washington DC We believe in fiscal policy for America that is based on facts. We believe in transparency and accountability because no matter where you are in the political spectrum, no one wants to see their tax dollars wasted. It’s June, 2025 and dear podcast listeners, we’re discussing a critically important fiscal issue that connects our food system, climate policy, and taxpayer dollars. Today we’re examining how agriculture lobbying interests have influenced policy decisions that ultimately cost taxpayers billions while potentially making our climate problems worse. Here with me today is New York Times bestselling author and journalist Michael Grunwald to discuss his forthcoming book. We Are Eating the Earth, the Race to Fix Our Food System and Save Our Climate, which comes out on July 1st. Mike, thanks for joining me today.

Michael Grunwald:

It’s great to be with you, Steve.

Steve Ellis:

We also have my colleague Josh Sewell on the pod because if we’re talking to ag policy, he has to be part of the conversation. Welcome back, Josh.

Josh Sewell:

I’m always happy to be here, especially talking to someone else who loves the Farm Bill.

Steve Ellis:

So I just finished literally about 30 minutes ago reading your book. It’s an excellent book and kind of a scary book. It presents a really stark thesis that humanity is cleared a landmass equal to the size of Asia and Europe to grow food, and our food system generates a third of our carbon emissions for our budget watchdog listeners who care about taxpayer dollars, what’s the connection between food policy and fiscal responsibility?

Michael Grunwald:

Well, look, globally, the world spends about 600 billion a year subsidizing agriculture and $300 billion of that is just direct handouts, and what we’re getting for it is the eating of the earth. I mean, look, we’re also getting a lot of food. It feeds the world and that’s important, but if you step back from all of this, one thing I’m saying is like, hey, two of every five acres on this planet are now cropped or grazed, right? We get all upset about urban sprawl. That’s one of every a hundred acres on this planet. As agriculture eats the earth as it uses 70% our fresh water, it’s the largest driver of deforestation, wetland destruction, water pollution. If we’re going to keep giving them money, it’s fair for us to ask for them to do their far part to protect our planet and our climate.

Josh Sewell:

If agriculture’s such a big driver of climate change or a contributor to climate change, even as someone who works in ag policy, I don’t hear a lot about climate change outside of some of our circles and agriculture’s role in it. So is the electric grid or transportation just sexier? Why is the reason we’re not looking at ag?

Michael Grunwald:

It’s a great question. I mean, look, I was mostly an energy and climate reporter. I wrote about all kinds of policy, but I’d done a lot of climate work and about six years ago it sort of occurred to me like, Hey, this stuff is a third of the climate problem and an even bigger percentage of these other problems, and it’s 3% of climate finance and 0% of the climate conversation. Why is that? I don’t know. But when I started writing about energy and climate 20 years ago, it was kind of in a similar position to where food is today where there were really no solutions on the table. The only one was biofuels, which as I’m sure we’ll discuss, is kind of a fake solution that actually makes these problems worse. There was no wind, no solar, so a lot can change really quickly, but certainly where the food problem is energy, we at least know what we need to do even if we’re not doing it fast enough, but we’re actually starting to do it while with food we don’t even know what to do. The problem is getting a lot worse and like I say in the book, we don’t know much and a lot of the things we think we know just aren’t so

Steve Ellis:

Well. Speaking of things that I guess we now know just aren’t so, although people seem to refuse to admit this, your book starts at least the first several chapters about the battles over biofuels and biomass and your narrative centers around Tim Searcher, a lawyer who becomes a food and land expert fighting against what you call bad science and bad politics. Without giving too much away about the book, what can you tell us about searcher’s battles and how the agriculture lobbying interests have influenced these costly policy decisions specifically, and our listeners are a smart crowd about indirect land use change or I luck?

Michael Grunwald:

Sure, yeah. I mean, Tim’s a character. I remember when I was starting to work on the book, I had one editor advise me, you don’t want it to be too much about the Holocaust and not enough about Anne Frank, which is a horrible thing to say, but Tim’s my frank I guess, and he is this guy who’s been banging his spoon on his highchair about land use now for about nearly 20 years. He was, as you say, a wetlands lawyer. Steve and I, we knew him way back when his obsession was the Army Corps of Engineers and it became our obsession as well, and he’s always been this brilliant, relentless, not always warm and fuzzy type of guy who does his homework, gets the facts and is just incredibly smart and often quite willing to tell you. So Tim, he stumbled into biofuels because he was a wetlands lawyer and his fear was that if we had too many biofuels that basically we would have more corn and that would end up draining a lot of wetlands and using a lot more pesticides.

What he ended up realizing to not to give away too many punchlines is that the climate analysis of biofuels and really of climate issues in general ignores land use. If you grow fuel instead of food, the basic problem is that somewhere else you’re going to have to grow more food and it’s probably not going to be in a parking lot. It’s going to be in a forest or a wetland that stores carbon and actually also absorbs carbon from the atmosphere and you’re going to lose that, and that has a major climate cost and the climate analysis of the day were just treating land as if it were free, as if there were no cost. And Tim ended up basically showing that biofuels were eating the earth, that they were using a lot of land and not replacing a lot of fossil fuels. The larger punchline is that biofuels overall, and they are terrible. They’re horrible for the climate. The more we have, the worse it’s going to be for the climate and for deforestation and biodiversity, but biofuels are eating about a Texas worth of the earth while agriculture in general is eating about 75 texas’s worth of the earth. So Tim ultimately realized that, hey, it’s biofuel. If it takes off, it really can destroy the planet, but agriculture is already destroying the planet,

Steve Ellis:

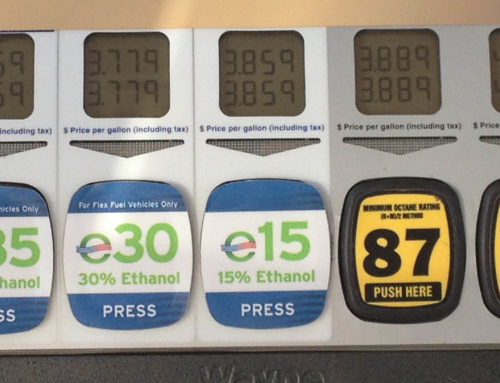

Right? Although at least agriculture has the benefit of feeding people, whereas biofuels, it’s inefficient. So we were certainly in a lot of those rooms and engaged in many of those battles over biofuels and biomass and RFS. The renewable fuel standard was the subsidy because one of the main subsidies, because it mandated a market for ethanol, and about that time there were other tax credits combined into the volumetric ethanol excise tax credit or vtech. You also wrote about how the world has embraced solutions that sound sustainable but could make it even harder to grow more food with less land. We’ve talked about biofuels in the show before, but what are some of the examples of these false climate solutions in agriculture and what do they cost the American taxpayer?

Michael Grunwald:

Well, look like you said, I mean biofuels is the classic one because really, I mean whether it’s vtech or whatever, it’s sort of like water flowing around rocks, right? They’re going to get their money and they’re going to get their markets. Right now it’s because of the rise of electric vehicles, the biofuels industry, which is essentially the corn and soybean industry, they’re worried that they’re going to lose their gravy train. So now they’re looking at sustainable aviation fuel and in Trump’s big beautiful bill which has cuts a trillion dollars worth of clean energy subsidies, it adds 45 billion for biofuels and it’s mostly for aviation and for good measure, they added language that says basically, since corn and soy don’t pencil out as a sustainable aviation fuel, they basically told the government to put their pencils down. They said, you cannot take land use into account because land use messes up the numbers and shows that it’s a climate disaster.

So again, that’s one example You mentioned biomass power is another one where there’s this kind of crazy idea that you can burn trees and somehow it’ll have no effect on the climate as opposed to just leaving the trees alone. I would also mention this global push for low yield regenerative farming because there’s this idea that it’s sustainable. There’s this idea that because it uses less chemicals or it’s nicer to the soil, maybe the animals have names instead of numbers that somehow this is like a big climate win. And there is not only billions of dollars coming in from the US government, but there’s talk globally of trying to pour trillions of dollars into really a international transition from this kind of extractive industrial agriculture to this kind of carbon farming regenerative agriculture that’s going to solve global warming. It’s going to take all the carbon that’s up in the sky and move it to the soil, and that is mostly bogus.

Certainly the carbon farming element is really, the science is terrible, but even the general regenerative push when there is some good stuff about regenerative farming, but this idea that we should be pouring billions of dollars into it because it’s going to be basically a kinder and gentler way to do agriculture. Again, if it produces less food per acre, it’s going to need more acres to produce food and it’s going to eat more of the earth. And you saw Biden put about 23 billion into what he called climate smart agriculture, and there was some good stuff in there, but most of it was for this kind of regenerative carbon trying to sequester carbon in the soil, which there’s really very little evidence for. And Trump is actually, he’s canceled some of it, but some of it he’s keeping going because nobody likes taking money away from farmers.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, we saw that one of our big concerns with the climate smart agriculture, that specific program, but even the whole push towards carbon sequestration through farmland is so much of it seems to be, and I think even there’s close to, I thought I saw this term in your book, Faith-Based

Michael Grunwald:

Conservation,

Josh Sewell:

And that’s something that I personally have been talking about for a long time with the folks that we work on, is that we want some science, we want some data to prove this. And what I think is fascinating about agriculture, which is why everyone should like ag policy, is that it is so diverse where you grow food and how you grow food and just what’s going on there. But I’m afraid that in the climate smart is almost becoming similar to biofuels where we just assume it’s good and now it’s become a way to make a lot of money. Do you see that carbon market moving forward?

Michael Grunwald:

That’s exactly what’s happening. And you can see how there’s this push on the left from Michael Pollan types and Al Gore and on the right from Bobby Kennedy and Joe Rogan, but then also from agribusinesses from Archer Daniels Midland and PepsiCo and Big food, the General Mills and Mars and the World Bank, and everybody wants to do this stuff. And you see these movies, carbon Cowboys, kiss the ground common ground, and you hear Woody Harrelson like, oh dude, you’re just going to the answer’s beneath our feet, man. It’s like all that carbon up in the sky is going to end up underground, kiss the ground, but there’s no science. And in fact, the science has really gone quite the other way. It’s shown. Not only is this stuff really difficult to measure, not only if you do store a little carbon underground, is it very difficult to know whether you’re going to be able to keep it underground, and more importantly whether if you’ve stored that carbon underground, whether you’ve basically moved it kind of shell game where you have more carbon over here but less over there.

And of course we’re paying the people who have more carbon, but the people who have less carbon don’t have to pay. But even beyond that, it seems to be there’s really scientifically, chemically, there’s no way to store a lot more carbon in your soils unless you put a lot more nitrogen in your soils and nitrogen has all kinds of its own climate problems. So this really is, it’s one of these things where people have glommed onto it because it’s a way to get agriculture. What you hear again and again is it’s like it can be part of the solution instead of part of the problem. But what that means is instead of basically telling farmers, your cows can’t burp so much methane, your fertilizer can’t emit so much nitrous oxide, it’s saying, Hey, here’s another way we can pay you. And that is very attractive politically to the right, left to everybody.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah. We noticed that when Secretary Vilsack in the Biden administration first started the Climate Smart Partnership, he tapped the Commodity Credit Corporation, which is the line of credit that USDA has renews every year, dates back to the fifties, which is also what he tapped in the Obama administration to fund blender pumps for ethanol that was forbidden, expressly forbidden by Congress. He used that. And it’s also what Secretary Perdue and the first Trump administration tapped to pay off farmers because they were being affected by the trade war and losing market share and soybean sales to Brazil.

Michael Grunwald:

Well, there’s definitely a sense that it’s like heads, farmers win tails, taxpayers lose, right? This does work out. I will say there was some good stuff in the climate smart Ag grants, and I’ll point out one, which to me is sort of like I don’t believe that government should never spend any money in agriculture, and particularly on the research side, what I think this climate ag stuff really should have been was more a kind of experimental program. And to their credit, they did at least talk about putting in a lot of money for measuring and verification and seeing if this stuff actually works. I think a lot of the money went towards stuff that we already know doesn’t work, but for instance, there was just one 7 million grant that went to a program to reduce methane from rice fields. And now it turns out that is a huge problem.

Our rice fields emit more methane. It’s a bigger greenhouse gas than it turns out. It’s more than the entire aviation industry and basic science is that the bacteria that emit the methane, they thrive without oxygen. So on flooded rice fields, and it turns out the way to dramatically reduce methane is to have the fields flooded less often. So there are these programs called alternate wetting and drying and furrow irrigation, but basically it’s like less water on your rice field and it works miracles, and they did satellite sensing to document it, and it was basically cutting the methane in half. And not only that, it sort of created this market, so they were able to sell carbon credits into the carbon markets. So unlike the soil carbon stuff, which who knows what’s really there, this was really measurable. There were corporations who wanted to buy the credits to reduce their own carbon footprint, and this stuff is now sustainable without government intervention. So now they’re on 150,000 acres of rice fields in the us, they’re expanding to Brazil. This is the kind of way that you can use the government to start something, a little research, a little development, and then the private sector take it over and it turns out to be good for the farmers, good for the environment, good for the planet. So I just point out that it’s not like this stuff is inherently dumb, but a lot of this stuff has been done

Steve Ellis:

Well. Certainly we’ve always said that government has a role in sort of basic research, and then once it gets developed, then it should be shifted off. Unfortunately, for instance, we were doing all our earmark analysis. There was one earmark that always showed up wood utilization. It’s like humans have been using wood for our entire existence, and so we’re still trying to figure up other things to use wood for, I guess burning whole trees for biomass.

Michael Grunwald:

Well, this is funny, the USDA actually, they have a list of kind of climate smart practices, and this is also getting into the weeds, but they have these conservation programs like EQUIP is one of the big ones where does it Environmental quality improvement program or something like that?

Steve Ellis:

Exactly. No, you

Michael Grunwald:

Hit it. And so they have all these programs that they’ve always been shoveling money to, and a lot of them have absolutely nothing to do with the environment. There’s all this money for fences or for irrigation projects. It’s like as if farmers are irrigating for the sake of the environment. And so basically what they did is they went back, they started the Climate Smart program in 2022, and then the Inflation Reduction Act poured 20 billion basically into conservation programs and told them to do climate smart stuff. So basically what they did was they reclassified all the stuff that EQUIP was already doing as climate smart. They sort of added that to the list of their climate smart practices and look, they put in a lot of money for cover crops, which I think are good. Not really climate smart, but good for the soil, good for the environment, reduce nitrates in our water systems, that’s fine. But most of the other things like brush clearing and all this different water infrastructure and stuff basically for feedlots to put to deal with the manure, which presumably feedlots need to do anyway, but they reclassified all of that as awesome climate stuff because last year the climate was sexy This year, I guess screwing the climate is sexy, so there’ll be more money for that.

Steve Ellis:

Well, I think a bunch of those things got cut because they had climate attached to them. Yeah, exactly. Like you said, they were smart for a little bit and then didn’t work out for ’em in the long run.

Michael Grunwald:

There was a lot of DEI stuff too, which actually was I thought did detract some from the climate mission, their effort to kind of spread it around to underserved and marginalized farmers and minority farmers. Maybe a valid thing to do, but I don’t think very good climate policy.

Josh Sewell:

And I think that brings up, when you’re talking about climate solutions and making progress some of this stuff, it feels like it feels good. We all love farmers and even critics like myself, we do in fact love farmers. I also really love efficient farm businesses, and I try to talk to, I really embrace that corporations are people too, and I’m like, all farmers are corporations now, basically almost all of them, they’re all businesses. And so I’m just kind of curious, since you’ve been doing this for a long time, how much do you think, what is the solution? Do we just need to help farmers farm better and what does that mean? How is government helping or is government a hindrance in

Michael Grunwald:

Doing? I mean, I think government can really play a role, but I think you also have to be realistic in that the ag industry just has outsized extraordinary clout. And this probably isn’t going to end with the government saying, screw you farmers. We’re not giving you any money anymore. We’re going to regulate you really hard and we’re going to make your lives miserable. That just doesn’t seem to be the way it goes. I will point out that in Denmark, and I know it’s Denmark, but Denmark just passed pretty much the Mike Grunwald approved agricultural reform bill, and it was essentially because they’ve done so much on energy and climate that suddenly agriculture looked like this. It was a huge percentage of their emissions. So it was clearly their turn in the barrel and they were like, oh God, we got to do something. Because the enviros there were kind of saying, let’s just shut down their pork and dairy industry, which would’ve been terrible for the global climate because Denmark has a very efficient pork and dairy industry.

So instead, what they really did was how can we do it better? And they poured money into research, into experiments of different climate smart technologies that’ll help their dairy cows burp less methane and will help them be even more efficient in their pig production and their crops. They’ll be able to have drought tolerant and gene edited and flood tolerant, you name it, doing all the things. But at the same time, the ag industry is going to have to return some of its land to nature. There’s going to be tax on agricultural emissions. There’s going to be a national effort to promote plant forward eating because meat and particularly beef is so much work for the climate than chicken and pork and then which is in turn worse than beans or lentils. So they’re going to do all the things. And I do think that shows that government can help.

I think you have to be realistic, and it’s going to probably have to be a kind of grand bargain where it’s like, look, we give you a lot of money. We’re going to keep giving you a lot of money, but hey, you’ve got to do your part. We want you to make food. We want help you make even more food, but you’ve got to do it with less of a mess. And I think we can talk about the details, but I think that’s the general theme of what we’re looking for because perfect isn’t on the menu, but better is better than worse.

Steve Ellis:

Well, I saw that in your book that search insure was in the midst of all of that, and there was one comment about reducing the pig impact on the climate. It was like, why don’t you just kill all your pigs and then you’ll have no emissions from pigs? And it was like, oh my God, Tim’s in my ear. I could hear that.

Michael Grunwald:

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. And this is a problem with, I think my book is fun. I tried to make it fun characters like Tim, there’s a narrative action, but at the heart of it, a lot of it has to do with these kind of boring concepts about incentives and accounting. And if the incentives account for land, if the incentives account for real emissions that include not just looking at the emissions from your little farm, but your effect on global emissions, that’s going to make a big difference. But right now, I talk about how I went to Brazil and I saw these ranches where they took these degraded ranches that had one cow for every four acres and transformed them into these incredibly productive ranches that had two cows per acre. So eight times as efficient, eight times as productive. But from a carbon market perspective, if those ranchers wanted to get paid, the best thing they could probably do, and this goes for government too, is they could just degrade their land, right?

Because as it is, they have more cows, so they have more methane emissions, they’re using fertilizer in their pastures so they have more nitrous oxide emissions. Nobody’s saying like, Hey, because using you’re eight times as productive, you’re using one eighth as much of the Amazon and you’re preventing all this deforestation and all these emissions. Right now we’re not accounting for that, and that’s a carbon market problem. It’s also a government problem. And that’s the sort of thing that I’m sitting here banging my spoon on my eye chair, read my book, fix this stuff. But so far there hasn’t been a lot of discussion of it.

Steve Ellis:

Well, I think it gets to one of the fundamental differences between agriculture and its impact on climate and say transportation and its impact on climate. I can ride a bike and get to a place instead of driving a car or I can walk or I can take a bus, and then I’m shifting it from 35 different, I think in one point. And there was 35 different people in their cars or 35 people in one bus. And so that’s different is that with agriculture, we still got to eat. And I mean you mentioned about feeding the world at the top of the podcast, but we’re not even feeding the world. I mean, there’s a lot of hunger and there’s a lot of inefficiencies in a lot of these areas. And you do hit on that quite a bit in there about how us agriculture and some other countries are so much more efficient than some of these other countries. And then how do we help them become more efficient? So then one, they use the land more effectively, they’re more nourished. And so one of these, that’s a challenge I think that agriculture has that’s very different than the other climate solutions.

Michael Grunwald:

No, that’s Or climate issues. Absolutely right. I mean, look, efficiency has become this kind of dirty word. It’s like kind of evil corporations dredging dollars out of the dirt, but it’s so important. Productivity is high yields. That is, again, if we can make more food per acre, we’ll need fewer acres to make food. And that’s important. And yes, sometimes that’s things people don’t like. That’s fertilizers and pesticides. But you saw what happened in Sri Lanka where they banned agrochemicals and their yields crashed and the government fell and there were food riots and everything went to hell. I mean, fertilizers helped stuff grow. Pesticides kill pests that stop crops from growing. This stuff is really important. And I think you got at this in the beginning of your question, there’s this kind of fantasy that we’re going to have kind of carbon neutral agriculture, agriculture. That’s the solution instead of the problem.

But the fact is agriculture always makes a mess. It always has. 10,000 years ago when we started farming before the industrial revolution, before all these giant tractors and toxic chemicals, we had already transformed a South America worth of land into farmland, and that had a huge impact on the climate as well as the bugs and bunnies that depend on all that natural land. So I think it’s important for agriculture to make less of a mess. That should be the focus, but we shouldn’t pretend that we’re going to be able to eat and somehow we’re going to feed 8 billion people with no impact on the land. The idea is just like, let’s try to use less of the land. And that is sometimes going to require more people hate factory farms, but factories are really good at manufacturing lots of affordable stuff, and that’s what we need our farms to do.

Steve Ellis:

Well, and we’ve always said is that agriculture on climate, it’s part of the problem. It’s part of the solution, but it’s also a victim as well. And you touch on that in there where one farmer saying, we can discuss how much it’s manmade or not, but these changes are real and we’re getting the five year floods and everything else and all that sort of impact.

Michael Grunwald:

That’s right. That’s right. I mean, look, I know when I talk about this stuff and people have complained that I’m all mathematical, I’m all logical, it’s all rational, and it’s true. I’m like, we need 50% more food by 2050 and we need to use 80% fewer emissions and the numbers this many quadrillion calories. But really this is a moral issue. I mean, we’re talking about feeding the world, we’re talking about doing it without chopping down the Amazon and the Congo Rainforest. We’re talking about people living in the floodplains in Bangladesh and indigenous people in the rainforest in Brazil, and small holder farmers in Africa. That is really important. And our current government’s posture, which is just basically we’re going to do whatever the farm bureau wants and the corn growers and they like biofuels, it’s going to increase the market for their corn. And yeah, it’s going to make grain and vegetable oil more expensive, but whatever.

It’s what they want, and we’re going to just throw out all this crop insurance and yeah, they’re probably going to end up farming these marginal floodplains that should really be restored to nature, and we’re going to pay them over and over again just like we do with regular flood insurance. These things have a real impact on the global food system, on taxpayer dollars and on the climate. So yeah, I know as Josh knows, this is wonky stuff and agriculture is this kind of blizzard of somebody called it. It’s like reading hieroglyphics with all these acronyms and that you have to memorize and the jargon, but we do vote on these issues three times a day, even if you’re not a farmer and 99% of us. So I do think it’s pretty important.

Steve Ellis:

Well, certainly we like numbers. We’re budget wonk, so numbers are welcome and facts and figures are all welcome on our podcast.

Michael Grunwald:

I’m among friends. I love it.

Steve Ellis:

Yes, yes, exactly, exactly. But so much of ag policy does seem to be, I mean, let’s face it, agriculture is basically the first industry for every country. And so they’ve been around a long time and everybody, and you talk about this somewhat in the book too, is, and even somebody kind of being that had an industrial farm and that was mad about their people having pastoral farm on the trucks that go by and everything else in America, we think of American Gothic and God made a farmer and have this romanticized view, but it’s just so much of our policy is driven by politics over science or even math,

Michael Grunwald:

Right? There’s this idea that the heartland is this kind of font of virtue. But I think it’s fair to say that you can be a budget wonk and I can write a book about some of the problems with agriculture and people can be doctors and lawyers and healers and influencers or whatever, because somebody’s growing our food. And so we do owe farmers a debt and they do a really awesome job of transforming sunlight and soil and rain into nutrition for all of us, and we should appreciate it, but also they get paid for it. We subsidize it. It’s okay to ask them to take responsibility for their actions too. And I know a lot of them like to talk about how they’re great stewards of the land and some of them really are, but I think we have to acknowledge that collectively they’re stewarding a mess. And that public policy has done a really bad job since most of its focus has just been shoveling money to the agricultural industry. And you can call it what are all the different programs, whether it’s crop insurance or direct loans or counter cyclical loans, or you name the equip or the CRP or the you name. All of these different farm programs, ultimately they shovel money to farmers. And that’s okay, we can keep doing that, but there’s also, there’s got to be some reciprocation on the other side, and that’s what I’m rooting for.

Steve Ellis:

You want the federal money strings should be attached. I mean, if you don’t want the strings, then don’t take the money. Even as Josh has frequently pointed out, is that because snap, the main nutrition program is part of the farm bill, a huge part of the farm bill, but there you have this discussion about work requirements, there’s payment limits, things along those lines. There’s no payment limits on farm subsidies, there’s no income thresholds or anything like that. So it’s really this sort of exalted sphere.

Josh Sewell:

People don’t believe me when I say I’m an optimist, but I am. I don’t think you can work on agriculture and not be an optimist, just like you can’t be a budget watchdog and not be an optimist. Eventually we’re going to turn some of these things around. But in agriculture, there is some of the solution does come from farmers, and I think it’s a real opportunity when farmers can be engaged and certain farm groups can be engaged. And I’m just curious your thought on this is that at this moment right now, this is now the third farm bill where that iron triangle of nutrition advocates, farm subsidy advocates and conservation advocates who have been lockstep together are no longer in lockstep, especially because of the nutrition programs. And the reconciliation bill is going right now, it could be 215 to 300 billion in cuts to nutrition programs and 50 to 70 billion in increases to farm subsidies. It’s the opposite. They’re taking from nutrition to pay for this, and that doesn’t happen. That’s never happened, at least in recent farm bills. And so that coalition, I think that Farm Bill Coalition’s done, that’s not coming back. And so it’s time for a new coalition. And so I’m just curious, what are some, not necessarily specific groups, but what are some ideas that we can move forward and say, this is what we should create that new Farm Bill coalition around efficiency science.

Michael Grunwald:

That’s really interesting. It’s funny, and again, I know this is a policy pod and I’ve always been a policy reporter, but I think you can ignore the politics. And one thing I do say, because it’s not like I have genius ideas of how we’re going to fix ag politics. What I do say is, if you’re a Democrat, what the hell are you doing? Because the policies are terrible. There’s bipartisan agreement on terrible subsidy policies, terrible biofuels policies, terrible regulatory policies that are basically just whatever the farmers and agribusinesses want, but at least the Republicans are getting something out of it. They’re getting votes. Farm country is now deep red. What are the Democrats doing? And even Democrats from non-farm states, I tell that funny story in the book about how this is when searching is when he was first starting to try to lobby against corn ethanol, and he’s in John Corzine’s office, the former Democratic senator from New Jersey, not a big corn state, and he’s making the case to his aide like, this is crazy.

You’re just subsidizing Midwestern agribusinesses. Your constituents are paying at the pump. And the aide says, look, the boss just doesn’t want to piss off the corn growers in Iowa. And Tim is like, wait a minute. Your boss was like the head of Goldman Sachs. He thinks he’s going to be president someday. And he says, Tim, they all think they’re going to be president someday. And so I do think there’s been this sense that sucking up to farmers is basically good politics everywhere, and I don’t have a great answer for that. But look on the policy side, like you said, research science, yeah, efficiency, but that you don’t have to push them, that you don’t have to push farmers that hard to be interested in efficiency. But I think there’s got to be these, I write about dozens of really promising potential agricultural and food solutions in the book. So that includes things like the alternative proteins, the fake meat, whether it’s plant-based or cultivated meat, food waste solutions, whether they’re behavioral or technological, lots of things that can be invested in basically to experiment with ways you can kind of chip away at these problems. And very little of that is happening. And of course under Trump who’s really targeted research money and seems to be quite a fan of just shoveling more money to farmers, especially to offset the damage of his tariffs, you don’t see it going in a great direction.

Steve Ellis:

They say that every senator looks in a mirror and sees a future president. Exactly. And I can remember in the 2008 campaign, Senator McCain, when he was in Iowa, he’d say, I have a glass of ethanol with my breakfast every morning.

Michael Grunwald:

Yeah, in 2004. In 2004 he was, or 2000 I guess he ran and he was against ethanol. He didn’t even compete in Iowa. And then by 2008 he was singing a different tune and Michael Bloomberg did the same thing. He had always been crusading against ethanol, and then he ran for president and he was like, huh, this stuff actually, it suddenly makes a lot more sense. Imagine that

Steve Ellis:

You mentioned the, I certainly found it interesting less on the taxpayer subsidy side, but about beyond beef and impossible and all of that. But then also then later you’re getting into this various tech innovation. It’s like, alright, so here’s this enormous salmon aquaculture, but then fail and then vertical farming and then fail. And then you had me going for a few pages that emia had a chance, but then fail and biofuel.

Michael Grunwald:

Yeah, I know it’s hard. I guess what I’m saying, all of this stuff is hard, and I try to be an optimist too, and look, there hasn’t been a lot of progress in this part of the world yet. But again, when I started writing about energy, there had been no progress on moving away from fossil fuels. And now just around the world, pretty much almost every new power plant is a clean energy power plant. So things change, but I think change is impossible if there isn’t even a discussion. Now, I’m not saying that because if we have a discussion then things are going to change, but they definitely won’t if we don’t. So really what I’m trying to do here is to at least say like, Hey, this stuff is a big fricking deal and nobody’s talking about it outside this very limited little world. I’m trying to kind of open the shutters and say, scream out the window and say like, Hey, let’s talk.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, I think that’s a good point too is so one of our colleagues, Sheila, who’s from Nebraska and still lives out there, she talks about how her families, they are farmers and her neighbors are farmers and they talk about how the weather is a lot harder now and how it’s harder to do stuff, but they don’t use the C word. They won’t say climate change. But having those conversations I think is actually something that we want to do too, is to find those solutions. And I think another thing moving forward is trying to get farmers off the hamster wheel. They are definitely planting to the programs because if you don’t, you’re not going to survive at times. And so we am not as quite the analogy you used earlier, but sometimes I like to say somebody’s the best way to help a drowning person is to stop holding them underwater. And that’s kind of what we have to do, I think with our federal incentives. But I completely agree that farmers don’t like regulation. I get it, but it’s a two-way street. This is a partnership when you’re getting money and I think there’s enough of ’em out there who want to do something different as long as it is that conversation that we’re not a top-down solution coming from Washington or from Miami or some other urban area.

Michael Grunwald:

If you follow farm policy, I guess if you follow budget policy writ large, it’s easy to just be depressed and throw your hands up in the air and say like, nothing ever changes. And look, I mean this is, humans are not so awesome at making sacrifices for the greater good when there’s not perceived to be an immediate crisis. We’re not all going to die tomorrow. We’re not really fighting World War ii. Again, climate is a different kind of problem. The environment is a different kind of problem. That said, we are the only species that can figure out what the definition of insanity is.

And so we don’t have to keep doing the same thing over and over if it isn’t working. And it’s always possible that we won’t, and we’re pretty good at inventing stuff and we’re pretty good at problem solving when we actually try to solve ’em. Part of what I’m saying is these are problems we have not actually tried to solve. And the people working on these issues in Washington, present company accepted, are often not trying to solve them. They have different goals, whether it’s to boost farm incomes or to get farm votes or to neutralize the farm vote, pick your poison. But I think these are problems that are solvable, or at least we know there are a lot of people working on them that could use some help from the government. And that’s what helped with energy not only solar and wind and nuclear, but even fracking, right?

Which was stuff that you had these initial government investments in research and then some in deployment and even some government risk taking that helps get this stuff to scale. And I think we’re going to need that for feed additives that can help cows burp less methane and bio fertilizers that can edit the genes of microbes so that they can fix nitrogen from the air, feed it to crops instead of using chemical fertilizer or bio pesticides that use the mRNA technology behind the COVID vaccines to constipate potato beetles to death. There’s all kinds of ways that government can help. There’s all kinds of cool things happening, but right now, what government seems content to do is just to keep shoveling money to farmers. And the bigger the farmer, the more money they get, the more conventional their approach, the surer they are, that they’re going to get the money.

Steve Ellis:

You certainly start the book and end the book saying that you’re trying to avoid Debbie Downer, and it is an entertaining book. It takes you a lot of different places. But yeah, it is pretty heavy at times. But you kind of begin and end with saying that and with some optimism,

Michael Grunwald:

I don’t pretend that it’s not going to be hard, but with a lot of things, if it were easy, somebody would’ve already fixed it,

Steve Ellis:

Right? I think at one point you’d said that we didn’t move from using horse-drawn carriages until we got a better technology cars and we didn’t move from cars to different technology. So there was sort of a thought of that how not until we’re actually our backs are against the wall or new technology comes, that it actually changes everything,

Michael Grunwald:

Right? Well, I do think that’s, I am optimistic about technology. I have a device in my pocket that I can chat with anybody anywhere on the planet and look up any fact known to mankind and use it as a flashlight. And I don’t think a few years ago people thought that was possible. So that is something that we’re really good at. That said, it is going to require some change and we are going to have to support the change makers.

Steve Ellis:

Well, Mike, congrats on the book and podcast listeners, you can catch up, Mike it now. It seems that New York Times, he’s going to be a contributing writer to the New York Times as well. So Mike, Josh, thanks for joining me again on the Budget Watchdog AF podcast.

Michael Grunwald:

Thanks so much for having me, guys.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah, always happy to be here. Well, there you have it. This is the frequency. Mark it on your dial, subscribe and share and know this taxpayers for common sense has your back America. We read the bills, monitor the earmarks, and highlight those wasteful programs that poorly spend our money and shift long-term risk to taxpayers. We’ll be back with a new episode soon. I hope you’ll meet us right here to learn more.