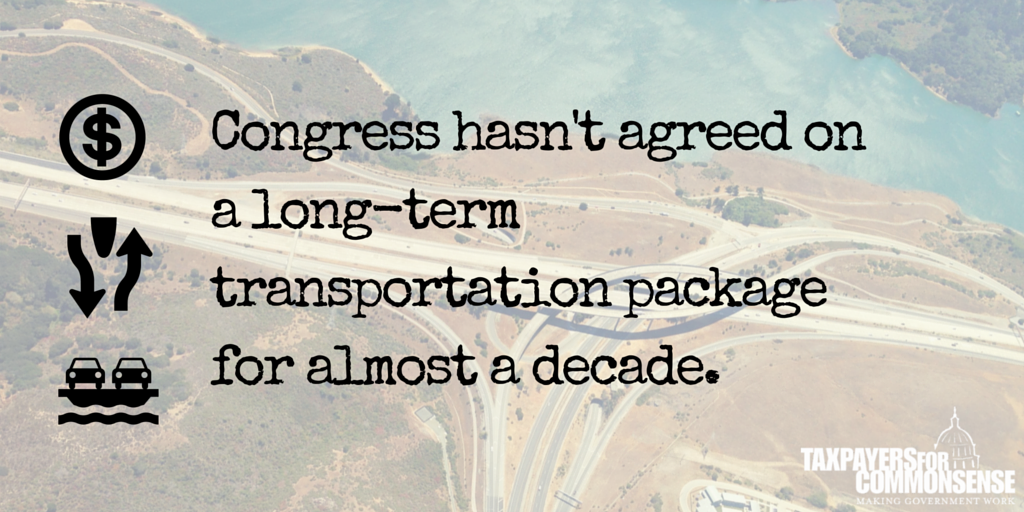

This week, the House of Representatives passed a long-term transportation spending bill that would provide $325 billion on transportation projects over the next six years. The Senate passed its own transportation bill (Developing a Reliable and Innovative Vision for the Economy or DRIVE Act) in the summer, and the two still need to be reconciled. With the exception of a 2-year extension in 2012, Congress has not been able to agree on a long-term transportation package for almost a decade; it has passed – count ‘em – 33 short-term extensions. Getting a long-term deal over the finish line will be the first test for newly minted House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI).

This week, the House of Representatives passed a long-term transportation spending bill that would provide $325 billion on transportation projects over the next six years. The Senate passed its own transportation bill (Developing a Reliable and Innovative Vision for the Economy or DRIVE Act) in the summer, and the two still need to be reconciled. With the exception of a 2-year extension in 2012, Congress has not been able to agree on a long-term transportation package for almost a decade; it has passed – count ‘em – 33 short-term extensions. Getting a long-term deal over the finish line will be the first test for newly minted House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI).

Unlike the DRIVE Act, the House’s transportation bill includes offsets to cover all six years, albeit at lower funding levels. The Senate bill only included offsets for the first three years, leaving a future Congress to figure out how to pay for the current one’s spending priorities. Both bills had funding shortfalls because Congress’s spending eyes are bigger than the taxes they are willing to stomach. The 18.4-cents-per-gallon federal gas tax was set more than 20 years ago and inflation, more fuel efficient cars and less driving overall have dramatically reduced its purchasing power. In short, it generates only about $34 billion per year to cover $50 billion in average transportation spending that Congress seeks. The Congressional Budget Office projects the cumulative shortfall will grow to about $148 billion by 2025.

The House got creative in finding offsets for the bill. Some of the offsets the Senate had used were taken for short term extension of the transportation program, some were used elsewhere, and others the House just didn’t like. Then they hit upon the idea of raiding the Federal Reserve surplus account, which is generated by fees charged to banks that are part of the Federal Reserve System. Ka-ching! Liquidating that account generates nearly $60 billion over ten years. After the offset dust settled, the House bill has funding for all six years, or five if they decide to go with the Senate’s higher spending level. Of course that is ten years’ worth of offsets for five or six years of spending.

The Senate’s DRIVE act guaranteed spending without offsets. In fact, less than ten percent of the offsets in that bill would occur during the first three-year spending spree and less than one-third of the new revenue would appear in the six year life of the bill. This is a pattern in Congress, as exemplified by the recent budget deal, which also relies on a decade’s worth of savings to pay for two years’ worth of spending.

Even if Congress does manage to find a way to agree on a long-term transportation bill, they are once again sidestepping the problems that make transportation spending so difficult. The gas tax as a source of revenue is going to be worse off, relative to desired spending levels, when the next bill expires. Also, Congress has avoided the problematic budgetary treatment of the Highway Trust Fund (HTF), which is relatively unique in that the spending is classified as both mandatory and discretionary, making it immune to most budget control and spending cap formulas that apply to other spending programs. Last year the Congressional Budget Office reported that this split budgetary treatment increases uncertainty, making it more difficult to understand the budgetary implications of federal transportation legislation, which leads to poor spending choices. As we have said before, besides insufficient revenues relative to spending, one of the biggest failings of transportation spending is the lack of prioritization.

Congress may be able to claim a major victory by the end of this year by enacting a long-term transportation bill. But it will be a pyrrhic victory if they don’t address the underlying failures and challenges in funding the transportation program. They will be asking the President elected in 2020 and the 117th Congress to do what they were unwilling to do.

Photo credit: jypsygen via flickr