US president Joe Biden signed a stack of climate-related executive orders on Jan. 27, rewriting federal policies on everything from national security and ocean conservation to relief for coal-reliant communities and environmental justice.

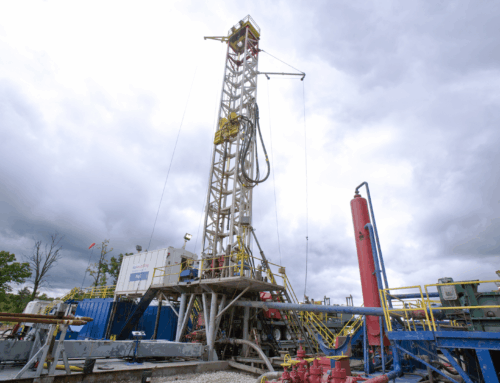

One of the most important of Biden’s orders places an indefinite moratorium on issuing new leases for oil and gas drilling on federal land and water, and launches “a rigorous review of all existing leasing and permitting practices.” While the directive will do nothing to change emissions in the short term, it’s a chance to fix the fact that federal oil and gas leasing is a notorious ripoff for US taxpayers and an unnecessary giveaway to oil companies.

“It’s very cheap to drill on public lands, and that needs to be fixed,” said Jenny Rowland-Shea, a senior public land policy analyst at the Center for American Progress. “We’re letting oil companies sit on those leases for pennies.” The federal leasing process, she said, “breeds speculation and waste.”

About one-quarter of total US emissions come from the production and use of fossil fuels from federal land, according to federal data (pdf), although more than half of those emissions come from coal leases, which the order leaves untouched. The order also does nothing to alter the status of the roughly 26 million acres of federal land that are under existing fossil leases, which account for about 22% of US oil production and 12% of natural gas.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic wiped out most oil companies’ appetite for spending on exploration, the Trump administration held a fire sale for drilling leases. Between 2017 and 2019, it sold off leases to more than 5 million acres and pushed to open vast stretches of the US coast to offshore production. The number of acres sold for the minimum federal bid of $2 per acre increased from 19% in 2017 to 25% in 2020.

A high volume of low-cost bids is a problem for two reasons. First, the price of leases on public land is far below the price for state- or privately-owned land. Second, it indicates that oil companies know the lease isn’t likely to yield much for themselves or for taxpayers. A 2020 review from the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office (pdf) found that between 2003 and 2009, revenue from the 72% of leases sold competitively, many for $100 or more per acre, was three times higher than revenue from non-competitive, minimum-bid leases. In other words, 26% of competitive leases produced oil or gas during their 10-year term. Only 2% of minimum-bid leases did.

Why bid at all for junk leases? Prices are so low, and oil companies’ financial imperative to ramp up drilling so great, that it has traditionally made sense to just snap leases up by the armful, said Andrew Logan, senior director for oil and gas at the sustainable investment advocacy group Ceres. “The industry is on a production treadmill,” he said. “They need to constantly drill new acreage to pay off existing debt and expenses.”

What’s more, the royalty rate companies must pay for what they do produce is low. For production on federal land, it hasn’t budged above 12.5% in more than a century, compared to the 16% to 19% that is common for state-owned land in the American West. According to Taxpayers for Common Sense, a DC watchdog group, low royalty rates caused the government to miss out on $12.4 billion in revenue from onshore leases between 2010 and 2019. Additionally, about half of the onshore acres oil companies have leased are not in production, meaning the land can’t be used for anything else—including clean energy production, recreation, or conservation—while oil companies keep it unused in their back pocket.

All of this amounts to a massive boon for oil companies, on top of $20 billion the industry already receives in annual direct subsidies from the US government. That puts the leasing program in the crosshairs of another part of Biden’s orders: to “eliminate fossil fuel subsidies as consistent with applicable law.” It’s likely that someday the administration will re-open some acres for oil and gas leasing (the order is pointedly not a ban on drilling) but those leases will likely become more expensive. Lease terms could even be recalculated to reflect the societal cost of carbon damage, a price tag Biden re-established a task force to study last week. The administration could also re-allocate acres with poor fossil-fuel potential for renewably energy uses or simply conserve them for wildlife, another priority outlined in the orders.

It will take years for Biden’s latest orders to translate into significant reductions of the country’s greenhouse footprint. To achieve deep, permanent emission cuts, the administration will need to push through new regulations on vehicles and power plants and work with Congress on clean-energy spending legislation, among other initiatives. But the orders do provide a blueprint for the administration’s climate priorities, and the new guidelines on federal leasing will ultimately dictate its carbon footprint. “This is really important for the trajectory for US oil production 10 or 20 years down the line,” Logan said. “It’s a resetting of our long-term direction on energy.”

Until then, Logan said, a more pressing concern for the industry is Biden’s call to replace the government’s fleet of cars and trucks with electric vehicles. The industry can endure losing some access to federal drilling rights as long as there’s strong demand for oil and gas. But it can’t afford to lose customers at a time when demand for fossil fuels is weakening, especially because it needs to continue raising the capital to drill in other parts of the country and world.

“What the industry fears most is that demand will peak and decline,” Logan said. “And if there’s any indication that the party is coming to end, that’s a huge concern to lenders and investors.”