Federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) manage hundreds of millions of acres of public land that are vital for resource development, biodiversity, recreation, and water resources. Around 62% of BLM lands and 49% of USFS lands are available for lease to private ranchers for livestock grazing for a fee under the federal grazing program.[1] However, this program has long been criticized for drastically undervaluing public resources and shortchanging taxpayers.

Federal Grazing Fee Falls Behind Market Rate

The current grazing fee formula was established by the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978 (PRIA) and continued by a 1986 executive order issued by President Reagan. The fee is calculated based on an animal unit month (AUM), the amount of forage a cow and her calf consume in one month. The total amount charged, due at the start of the month, is the product of the annual fee and the number of animals that will be grazing on the leased parcel. Each year, the fee is set using a formula that adjusts a base value by three factors: private land grazing lease rates, beef cattle prices, and livestock production costs. The fee cannot fall below $1.35 per AUM, the statutory minimum under the PRIA.

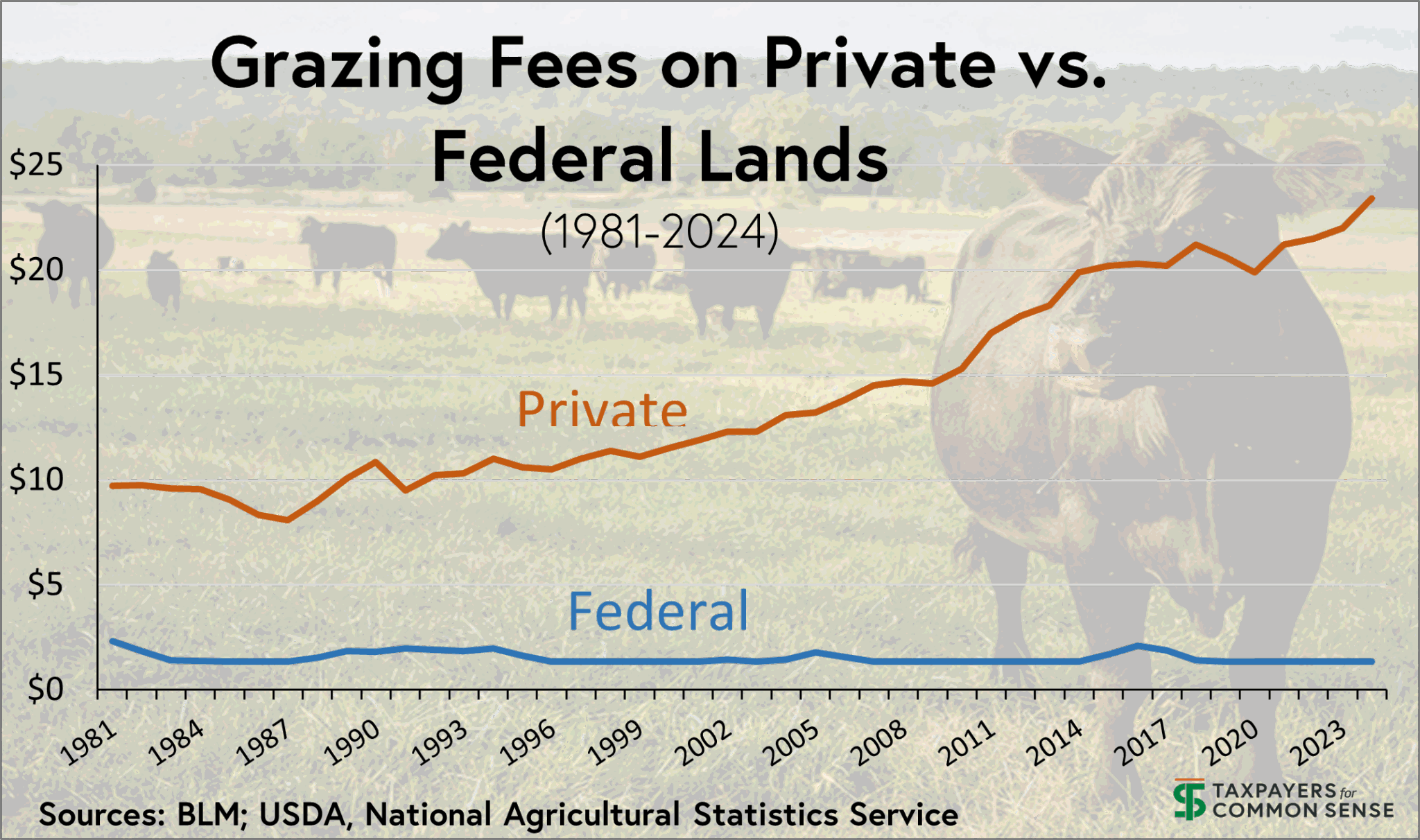

Since 1981, when BLM and USFS standardized their grazing fees, the rate has ranged from the legal minimum of $1.35 per AUM (about 55% of the years) to a high of $2.31 per AUM in 1981. The average fee over the decades is just $1.53 per AUM. In 2019, the fee was reduced from $1.41 to $1.35 per AUM and has remained at that level since.

The gap between federal grazing fees and market rates for private land grazing has widened considerably. A 2015 analysis found that federal grazing fees were just 7% of the cost of grazing on comparable private and state lands.[2] In 2024, the average monthly grazing fee for private leases in 17 western states was $23.40 per AUM.[3] Even adjusting the federal fee for inflation since 1981, it would only be $7.74 per AUM—still far below private and state rates.[4]

Fiscal Impacts on Taxpayers

The artificially low grazing fee creates a substantial subsidy for livestock operators at taxpayers’ expense. Ranchers using federal lands pay a fraction of what they would on private lands, while the costs of administering the federal grazing program far exceed the revenues collected. For example, in FY2017 BLM spent $32.4 million administering the program but only collected $18.3 million in grazing fees.[5] The failure to re-cooperate administrative costs, on top of additional funding appropriated by Congress for grazing management, leaves taxpayers effectively subsidizing the program to the tune of $100 million annually.[6]

Grazing can also lead to environmental damage, such as harm to native species’ habitats and the spread of invasive weeds, requiring costly remediation. A 2024 analysis found that more than 56 million acres of BLM land failed to meet land health standards, with grazing identified as the primary culprit.[7] Furthermore, half of all federal grazing fee receipts are earmarked for “range improvements,” leaving taxpayers on the hook for remediating land damaged by heavily subsidized grazing on public lands for pennies on the dollar.

Conclusion

The federal grazing program undervalues public lands and resources, charging fees that are drastically below market rates. This system benefits a small segment of the livestock industry while costing taxpayers millions each year.

The low fees also fail to account for the fiscal liabilities tied to remediating land degraded by grazing. To protect taxpayers and ensure public lands are managed responsibly, a comprehensive reevaluation of the grazing fee formula is long overdue. Fair market rates and the true costs of administering the program must be factored into any reforms to ensure public lands serve the broader public interest.

[1] Congressional Research Service (CRS), “Statistics on Livestock Grazing on Federal Lands: FY2002 to FY2016,” August 2017. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44932/3

[2] Center for Biological Diversity, “Costs and Consequences: the Real Price of Livestock Grazing on America’s Public Lands,” January 2015. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/grazing/pdfs/CostsAndConsequences_01-2015.pdf

[3] USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, Grazing Fees: Animal Unit Fee, 17 States, January 2025. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Grazing_Fees/gf_am.php

[4] Inflation adjustment calculated by Taxpayers for Common Sense (TCS) using Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) provided by U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[5] CRS, “Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues,” March 2019. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RS21232

[6] TCS calculations based on USFS and BLM appropriations. However, information is limited, as USFS appropriations grazing management have since been removed from appropriations tables and other USFS program appropriations may support grazing but not separately identifiable.

[7] Western Watersheds Project, “Livestock Leading Cause for Failing Minimum Landscape Health Standards,” May 2024. https://www.westernwatersheds.org/2024/05/much-of-u-s-rangeland-in-poor-ecological-condition/

- Photo by Cullen Jones - Unsplash