When the Trump administration first pushed to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska to oil exploration, it predicted that drilling would generate a windfall for the federal Treasury: $1.8 billion, by a White House estimate.

But two years later, with the expected sale of the first oil and gas leases just months away, a New York Times analysis of prior lease sales suggests that the new activity may yield as little as $45 million over the next decade. Even the latest federal government estimate is half the figure the White House predicted.

The lofty original projection was just one element of a campaign within the administration to present in the best possible light the idea of opening the refuge’s coastal plain after decades of being stymied by Democrats and environmentalists, according to internal government communications and other documents reviewed by The Times.

Opponents of exploration have said the 19-million-acre refuge, one of the largest expanses of pristine land in the United States, could be forever damaged in pursuit of oil that would bring little benefit to American taxpayers.

The administration, bent on proving them wrong, turned to the federal bureaucracy to help make its case, the records show.

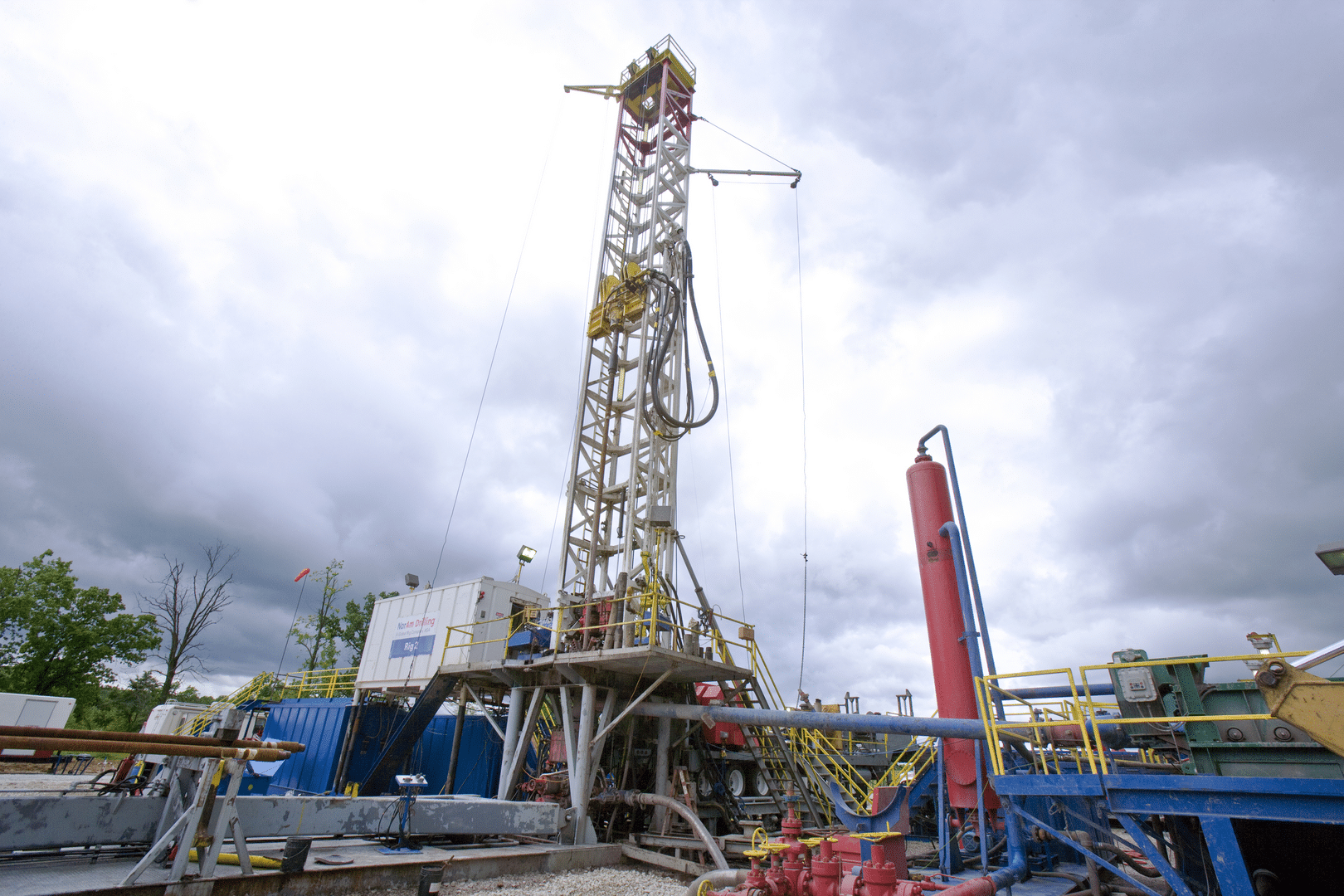

Even before plans to allow the lease sales were completed and approved by Congress in late 2017, the Interior Department pressed for new — and possibly rosier — assessments of the prospects for oil discoveries that would entail field research in the environmentally fragile refuge, according to the documents.

In revising a draft plan for the new assessments, officials played down evidence that the refuge might not have much oil, deleting references to disappointing wells nearby.

They also pushed scientists to provide studies and other information so quickly that some expressed concern over the speed of the process, according to the documents, which were obtained through public records requests by Trustees for Alaska, an environmental law firm that has opposed oil exploration in the refuge.

An Interior Department spokeswoman said the agency “absolutely” respected the work of its scientists and staff, and had not interfered with it in any way. She said negative information about nearby wells was not pertinent to prospects in the refuge.

The debate over drilling in the refuge goes back decades and could have significant ramifications for environmental groups, lawmakers in Washington and Alaska, and the oil companies who may bid.

Republicans made major advances toward drilling during the first two years of the Trump administration, when they controlled both Congress and the White House. But Democrats, since winning a majority in the House last November, have tried to slow or halt the drive toward lease sales.

An environmental-impact statement on the plan to sell leases is still in progress. The department spokeswoman said it should be completed next month; then, after a monthlong comment period, the sale process could begin. But environmental groups have vowed to take the administration to court, if necessary, to stop it.

And on Tuesday, Joe Balash, the Interior deputy secretary who as head of the Bureau of Land Management was overseeing the leasing program, resigned, effective Aug. 30. He said he was taking a new job, yet to be announced. The Interior Department has made less progress in its efforts to learn about oil prospects in the refuge, which could affect lease prices.

A proposal for seismic studies — which could help locate oil reserves but could also harm polar bears and other wildlife — was shelved in February, though it could be revived this winter. Another plan, for aerial surveys, went nowhere.

Government studies in the 1990s estimated as much as 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil in the 1.5 million acres of the refuge’s coastal plain, the area that could be opened to drilling.

But data from the only exploratory well ever drilled there — the so-called KIC-1 well from the mid-1980s — has been kept confidential. The Times reported this year that a decades-old legal battle provided clues that the results of that test well were disappointing. And with no new studies imminent, potential lease buyers will have no fresh information to help them decide how much to bid.

Still, the Trump administration predicted in its first proposed budget, in May 2017, that lease sales in the refuge would generate $1.8 billion over a decade. And for months afterward, as the White House and Republicans in Congress worked on legislation to permit the lease sales, they used the potential payout as political leverage.

But revenue estimates ever since have been substantially lower.

In fall 2017, the Congressional Budget Office projected $1.1 billion over a decade — a figure promoted by Senator Lisa Murkowski, the Republican from Alaska, when she worked with the White House to include oil exploration in the refuge as a revenue generator in the president’s tax overhaul.

Ms. Murkowski and others have pointed out that if oil is eventually produced in the refuge, the federal government will gain more revenue from per-barrel royalties. But few people expect drilling, if it occurs, to begin before 2030.

The Congressional Budget Office now estimates that the lease sales would bring in $900 million in federal revenue over the next decade, a figure it said was based on federal lease sales not only in onshore and offshore Alaska, but also in the Lower 48 states. But even that amount may be overly optimistic.

Since 1999, state and federal lease sales elsewhere on Alaska’s North Slope have yielded an average of $54.80 an acre, adjusted for inflation. Even if all 1.5 million acres of the refuge’s coastal plain were leased, at that price the federal government would receive about $45 million over a decade, The Times’s analysis of lease sales data shows. (Total revenue would be close to $90 million, but under the terms of the leasing program the State of Alaska would get half.)

Estimates by a watchdog organization and opponents of drilling also fall well below the administration’s. In a new estimate provided to The Times, the watchdog group, Taxpayers for Common Sense, detailed what it said was a likely scenario for the sales: bids on only about half the acreage, at a price of a little more than $53 an acre, which is the average for state and federal lease sales on the North Slope over the last five years. That would raise $20.8 million over a decade.

“It is hard to view these Congressional Budget Office estimates as based on reality,” said Ryan Alexander, the group’s president.

Separate from the budget estimates, the documents reviewed by The Times — thousands of pages in all — capture the worries of scientists and other specialists about the speed at which the administration has pushed to open the refuge and the potential effects of moving so quickly.

In 2017, a manager wrote in an email that a political appointee overseeing the research process had voiced concerns about the United States Geological Survey, an Interior agency, not “being given carte blanc” to do fieldwork in the refuge that summer as part of the push to update assessments of the oil potential there. Another email said the same appointee had asked why a research team’s helicopter wasn’t allowed to roam freely in the refuge.

The plan to conduct that fieldwork had been submitted to another Interior agency, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, without the required notice for such activity in the environmentally sensitive refuge.

Later, Fish and Wildlife officials were asked to change agency regulations to eliminate any time restrictions on scientific exploration in the refuge.

A Fish and Wildlife planner wrote in an email that the result would be to open the refuge “to an unending window to allow exploration plans.” (Changing the regulations eventually became unnecessary with the passage of the 2017 tax law, which put the Bureau of Land Management in charge of the lease program.)

She also noted that another document falsely implied that the federal government had been engaging with Native Alaskans on issues related to the refuge. “In fact we haven’t done anything,” she wrote. “We are already WAY behind the 8 ball in fulfilling our responsibility to communicate meaningfully with Tribes.”

In August 2017, as the process wore on, Fish and Wildlife staff members noted that Interior officials seemed to be growing impatient. “Looks like the Dept. is anxious to get something going with exploration/assessment,” a manager in Alaska wrote.

As scientists laid the groundwork for the administration’s new policy, some also noted the potential for a disappointing outcome.

The proposal for fieldwork in summer 2017 had come from David Houseknecht, an official with the geological survey, who noted that studies in the late 1990s had found little evidence of oil-bearing rock formations in the area.

In a speech later in 2017 to members of Alaska’s Resource Development Council, Mr. Houseknecht said the two-decades-old studies had not been updated. “We have not assessed or reassessed the ANWR area for 20 years because there’s no new data,” he said, using the acronym for the refuge. And the old data, he said, “are of such poor quality.”

When the Interior Department drew up plans in 2017 to update assessments of the potential oil reserves in the refuge, officials stripped out disappointing findings about test wells drilled just outside the area. The details were included in a draft but removed from the final plan, a comparison of the documents showed.

In response, the Interior spokeswoman noted that only one well had been drilled in the coastal plain, and that only one seismic survey had ever been done. “Other wells and geophysical studies do not apply to the coastal plain,” she said.

Even with all of the discussion about the refuge, major oil companies have been relatively quiet about whether they intend to bid. Some people in government and in the industry attribute this to a lack of interest based on the companies’ own data-gathering over the years. Others say the companies are probably just trying not to tip their plans to competitors.

The question will not be answered, of course, until bidding begins.

“Will it be a stupendous billion-dollar bid? Probably not,” said Larry Persily, a former federal gas official responsible for Alaska, who noted that there was no shortage of oil or gas reserves now. “Maybe it would be good to have the lease sale and find out if there is any interest,” he added. “And we can move on.”