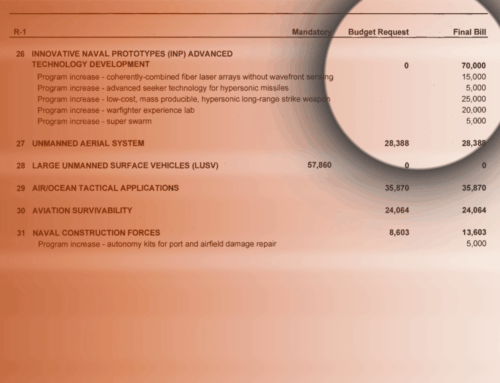

In Washington, every budget season comes with a second act. After the White House submits the Pentagon’s official request—which totaled nearly $1 trillion for FY2026—Congress receives a pile of “unfunded priority lists” (UPLs). These wish lists, required by Congress and filed by service chiefs and combatant commanders, are nominally designed to highlight Pentagon “priorities” that were left out of the Pentagon’s formal trillion-dollar request (how big a priority is it really). In reality, they serve as a convenient justification for lawmakers looking to ladle billions more dollars into the Pentagon’s already-bloated budget.

The accelerating price tag of these wish lists is particularly concerning. For fiscal year 2026, the lists totaled $53 billion, nearly triple the $18.4 billion requested just two years earlier. The Indo-Pacific Command asked for $11.9 billion, a 241 percent increase since 2024. The Air Force added $11.7 billion in unfunded wants, a 376 percent surge. The Space Force UPL ballooned from a rounding error into a near-$6 billion side-budget, a 1,152 percent increase in two years. These are not marginal gaps. They are requests for shadow appropriations comparable to the annual defense budgets of Britain or France.

What makes matters worse is that even senior Pentagon leaders have long questioned these lists. Former defense secretaries and comptrollers have warned that they distort rather than clarify priorities. Items on the lists are not weighed against other needs, nor are they subjected to the same justification process as the core budget. Some commanders have even pleaded with Congress not to raid official requests to pay for “unfunded” extras. Congress often ignores them.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has just added another layer of concern. A recent audit of the process found that between 2020 and 2025, UPLs swelled from $14.7 billion to $30 billion a year, totaling $134 billion over that period. More troubling, five of the 11 components GAO reviewed—including the Army, Northern Command, Indo-Pacific Command, the National Guard Bureau, and Special Operations Command—failed to include information required by law. Missing were such basics as which sub-activities and program elements the requests would fund, why the items requested were not funded in the president’s budget, and how funding would affect the Pentagon’s future five-year spending plan. Without these details, GAO concluded, Congress lacks the data to make informed decisions.

Even if the justifications submitted with UPLs were required to be more comprehensive, a larger problem would persist. Unfunded lists are catnip to appropriators looking to pump up the topline. Contractors reap billions in contract awards through this process. For taxpayers, the result is the opposite of discipline. When everything is a priority, nothing is.

The Pentagon budget should reflect a holistic strategy and hard trade-offs, not wish lists. Congress created the requirement for UPLs in 2017. It can repeal it now. Until it does, expect the Pentagon’s budget to keep expanding on two tracks—the official one that is already unsustainably large, and the shadow track that grows faster still.