Taxpayers are increasingly subsidizing the entire supply chain of bioenergy production. Numerous federal farm bill programs subsidize the production of bioenergy crops used in biofuels or bioenergy (heat and power) production, such as decades of government-set minimum prices, marketing loans, direct payments, shallow loss entitlements, and others. The programs, however, merely supplement subsidies for the production of biofuels themselves – for instance, corn ethanol and soy biodiesel – and a myriad of federal production mandates, loan guarantees for bioenergy facilities, research and development funding, fueling infrastructure tax credits, and other federal supports. If that wasn’t enough, the farm bill’s Biomass Crop Assistance Program (BCAP) also subsidizes the establishment of new bioenergy crops and the collection, harvest, storage, and transportation of crops to bioenergy facilities. Increasingly, bioenergy crops are also becoming eligible for federal crop insurance subsidies; as a result, the business risks of producing biofuels and biofuels crops are shifted disproportionately onto taxpayers’ backs.

This laundry list of subsidies was expanded by the 2014 farm bill’s creation of new crop insurance subsidies for special interests such as sweet and biomass sorghum, alfalfa, pennycress, and sugarcane – all crops used in biofuels production. Adding new crops to the federal crop insurance program increases costs to taxpayers as the traditional portfolio of eligible crops like corn and soybeans is expanded to include new special interest carve-outs.

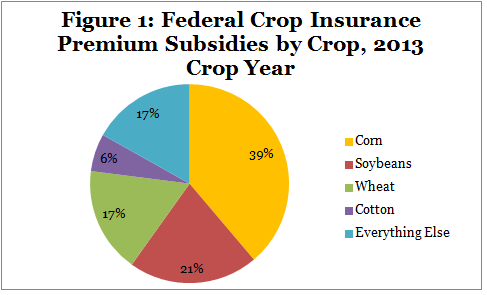

Breakdown of Federal Crop Insurance Premium Subsidies

Federal crop insurance is a highly subsidized program that allows agricultural producers to shift much of their business risk onto taxpayers. Originally designed as a way to help producers recover from natural disasters, it has since morphed into an income guarantee program for the most profitable farm businesses. Primarily benefitting growers of only four crops (cotton, soybeans, wheat, and corn – a large portion of which is used for biofuels production), crop insurance is now the most expensive taxpayer support for agriculture, outstripping all other agriculture safety net programs. It is a shining example of a government program filled with costly inefficiencies that detract from its goals and produce unintended consequences. On average, taxpayers pay 62 cents for every dollar of crop insurance premiums that a producer selects. While crop insurance has cost taxpayers less in recent years, in Fiscal Year 2012, government costs totaled a record $14 billion.[1]

Figure 1 shows that over 80 percent of federal crop insurance premium subsidies go to three major crops used in U.S. biofuels production – corn, soybeans, and wheat – in addition to cotton. [2] Over 90 percent of U.S. ethanol is produced from corn; in 2014, corn ethanol production, which uses 40 percent of the U.S. corn crop every year, reached an estimated 14.3 billion gallons.[3] Soybeans are the primary crop used in biodiesel production, but the fuel can also be derived from used cooking oil, animal fats, and other vegetable oils. About one-fourth of the U.S. soybean crop is used for soy biodiesel production each year.[4] Wheat can be used in ethanol production, but it is sparsely used compared to the large portion of corn and soybean crops dedicated to biofuels production.

New Special Interest Carve-outs for Bioenergy Crops

The number of crops covered by crop insurance has already ballooned to more than 120 over the past decade, and with new special interest carve-outs created in the 2014 farm bill, that number will increase to 130 or more. Some of the additions benefiting the biofuels industry include the following:

- Alfalfa: Development of alfalfa crop insurance was declared “as one of the highest research and development priorities” in the 2014 farm bill through an amendment offered by Sen. Moran (R-KS) even though it is one of the least risky crops to grow in the U.S. According to his press release, “The Risk Management Agency (RMA) is supportive of alfalfa insurance but is currently prohibited from working on research and development without this amendment.”[5] The 2013 House farm bill, and final 2014 farm bill, also included priority consideration for alfalfa crop insurance.

- Pennycress: Crop insurance for pennycress, a weed being tested for use in biodiesel production, was added to the 2014 farm bill via an amendment added to the 2013 House farm bill by then-Rep. Schock (R-IL). In 2009, Schock met with U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials to devise short- and long-term plans to obtain insurance coverage for pennycress, which is grown in Illinois. He also secured a $500,000 earmark in FY10 for a Peoria “Demonstration Plant for Biodiesel Fuels from Low-Impact Crops” which uses pennycress as a feedstock in its production process. Schock resigned from Congress in March 2015 given an impending “Congressional ethics investigation into reports that he used taxpayer money to fund lavish trips and events.” [6]

- Sugarcane: Sugarcane received priority consideration for crop insurance subsidies in the 2014 farm bill despite the existence of an additional and separate farm bill section that props up the industry through taxpayer-subsidized loans, government purchases, and other federal subsidies.

- Sweet or biomass sorghum: New crop insurance subsidies for biomass and sweet sorghum for use in biofuels production were inserted into the 2014 farm bill by Sens. Donnelly (D-IN) and Roberts (R-KS) at the request of the National Sorghum Producers and Kansas Grain Sorghum Producers Association.

Other Crop Insurance Carve-outs for Bioenergy Crops

While these new Congressional mandates for crop insurance policies were added to the most recent farm bill, new policies are normally considered through the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation’s (FCIC) approval process. Once a policy suggestion is submitted by a company, trade association, or crop insurance consultant, the FCIC Board reviews the application and decides whether to approve the new policy. If selected, the new crop or technology is then eligible for taxpayer subsidies.

Camelina and canola are examples of biodiesel crops approved for crop insurance subsidies by the FCIC in 2012.[7] That same year, the FCIC Board also approved a policy to insure Syngenta’s high amylase and blue corn types, known as Enogen, for use in corn ethanol production in approved states like Kansas.[8] Policy research and development contracts can also be awarded to assess the feasibility of new insurance subsidies for a particular crop or type of crop production. In 2011, two contracts were awarded by RMA to: (1) determine the feasibility of insuring corn stover, an agricultural residue used in cellulosic ethanol production by various companies, including POET, the largest ethanol producer in the U.S.; and (2) “review what types of woody biomass are being produced at a level that would allow further research into the viability of developing a crop insurance product.”[9] Two years later, in 2013, RMA found that these two types of crop insurance would be infeasible, likely because in the former case, corn itself is already subsidized through the federal crop insurance program.[10] Despite findings such as these, Congress has a history of circumventing USDA’s normal policy approval process and mandating taxpayer subsidies for certain special interest crops.

Conclusion

Now more than ever, the federal government should be scaling back – not expanding – its role in subsidizing the long supply chain of biofuels production. While the largest subsidy for corn ethanol production, the 45-cent-per-gallon ethanol tax credit, expired at the end of 2011, numerous subsidies still exist, ranging from crop insurance subsidies for corn production all the way to tax credits for converting fueling infrastructure to accommodate higher blends of corn ethanol. The 2014 farm bill expanded bioenergy subsidies by prioritizing crop insurance subsidies for everything from sugarcane to sorghum. With an $18 trillion and growing national debt, policymakers need to say no to special interest carve-outs and instead find ways to make the farm safety net more cost-effective, accountable, transparent, and responsive to our nation’s current fiscal situation and market conditions.

For more information, visit www.taxpayer.net, or call 202-546-8500.

1http://www.rma.usda.gov/aboutrma/budget/14costtable1.pdf

2http://www3.rma.usda.gov/apps/sob/current_week/crop2013.pdf

3http://ethanolrfa.3cdn.net/23d732bf7dea55d299_3wm6b6wwl.pdf

4http://www.usda.gov/oce/commodity/wasde/latest.pdf

5http://www.moran.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/news-releases?ID=69320720-3c20-4342-9b17-0b6454b86561

6http://www.cnn.com/2015/03/17/politics/aaron-schock-resigns/

7http://www.rma.usda.gov/fcic/2012/31managers.pdf

8http://www.syngenta.com/country/us/en/agriculture/seeds/corn/enogen/corn-growers/pages/enogen-traited-corn-hybrids.aspx , http://www.rma.usda.gov/bulletins/managers/2013/mgr-13-002.pdf

9http://www.rma.usda.gov/fcic/2011/817managers.pdf

10http://www.rma.usda.gov/pubs/2013/portfolio/portfolio.pdf

Photo credit: USDAgov via flickr