View/Download this article in PDF format.

For centuries, coal producers in the U.S. regularly abandoned their mines when on-site operations ended, leaving tens of thousands of hazardous features with substantial cleanup costs scattered throughout the country. To prevent such harmful practices, legislation was passed in 1977 requiring coal mining operators to restore all land affected by their operations, and post a bond to cover reclamation costs in the event they fail to complete such work themselves. With many coal companies now under financial strain, the strength of the law’s bonding requirements, particularly the ability it grants certain companies to “self-bond,” is being tested. As a result of insufficient guarantees provided by self-bonding, taxpayers may be saddled with billions in new reclamation costs.

Background

Coal industry bonding requirements were designed to prevent taxpayers from paying for reclamation after Congress recognized how costly it would be to clean up historically abandoned coal mines. The full extent of the problem is unknown, but authorities have been working to clean up more than 500,000 acres of hazardous coal sites that were abandoned before 1977. In that year, Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) to begin addressing the problem on a national scale.

Since then, the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) – the regulatory authority created by SMCRA – has spent more than $8 billion cleaning up abandoned sites. OSMRE estimates it will take $4 billion more to reclaim the most harmful remaining sites, and another $5 billion to finish reclamation work on all features abandoned before 1977. The funds largely come from the Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Fund established by SMCRA that’s funded through an AML fee on all coal production.

Reclamation Bonds

SMCRA also mandated that coal companies post reclamation bonds. Coal mine operators must submit a reclamation plan with their application for a permit to begin production. After the plan is approved, but before the permit is issued, the operators must demonstrate they will provide adequate funds for the cleanup of their mining projects, in the event they are abandoned. This is done by requiring the producers to post a reclamation bond. There are three types of reclamation bonds:

- Surety bonds: an agreement by a surety or insurance company to compensate the regulatory authority for the costs of any outstanding reclamation work not performed by the coal mine operator. Coal producers secure such a bond by paying service fees to the surety company.

- Collateral bonds: a bond backed by the market value of assets owned by the coal producer. It must confer to the regulatory authority a first lien, or right, to the value of the assets in any bankruptcy proceeding to cover reclamation costs.

- Self-bonds: a bond secured only by finances of the coal operator that are deemed sufficiently healthy to cover the costs of reclamation at a later time.

The alternative system of self-bonding was designed with the idea that a sufficiently large and successful coal mining company would never have trouble covering reclamation costs. To qualify, companies must meet OSMRE’s requirements for self-bonding eligibility:

“To remain qualified, self-bonded permittees must maintain a tangible net worth of at least $10 million, possess fixed assets in the U.S. of at least $20 million, and either meet certain financial ratios or have an “A” or higher bond rating.

Self-Bonding Concerns

In recent years, coal companies have qualified for self-bonding in ways that were not anticipated by the original self-bonding rules promulgated by OSMRE in 1983. Specifically, large coal companies have used the financial statements of their subsidiaries to prove they have the assets available to cover reclamation costs. The practice evolved from a provision in the original rule that allowed operators to post self-bonds using the financial statements of their parent companies. The assumption was that a parent company’s financials would serve as a backstop for any reclamation liabilities in the event a producer abandons a mine. The same does not hold true for a subsidiary in the event its parent company abandons a mine.

The utilization of these loopholes by coal companies that are increasingly unlikely to be able to cover their mining cleanup costs represents a huge potential cost to taxpayers. Peabody Coal is currently under investigation by OSMRE for using its subsidiaries to qualify for self-bonding while the company’s own finances worsen. Arch Coal Inc also claims to be eligible for self-bonding through its affiliate Arch Western Resources, even though the parent company’s 2014 securities filings fail to meet OSMRE’s eligibility requirements.

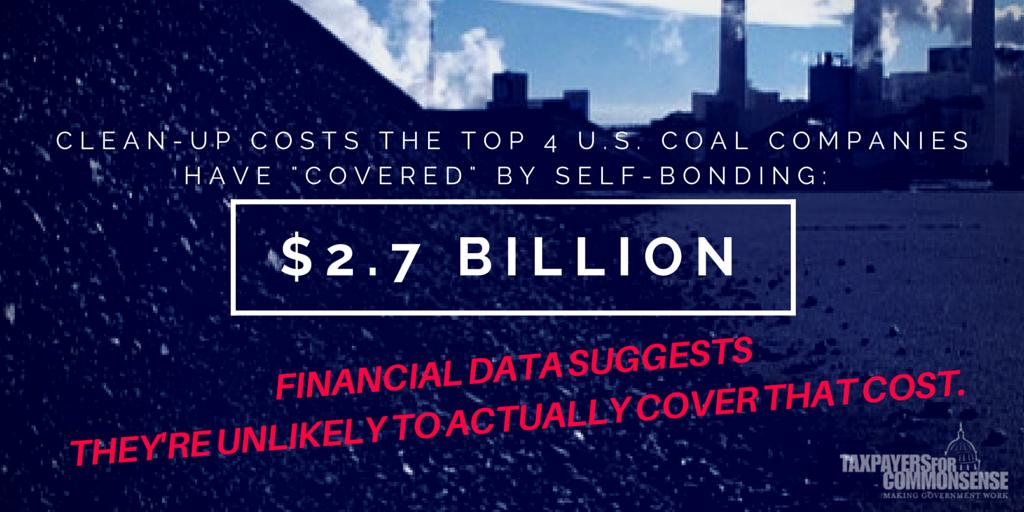

If a self-bonded coal company is unable to cover the cost of reclamation, such as in the cases of substantial debt or bankruptcy, their liabilities are left uncovered and the federal government will be left with the cost of cleaning up their mess. It is estimated that the four largest coal companies in the U.S., Peabody, Alpha, Arch Coal and Cloud Peak Energy, have about $2.7 billion “covered” by self-bonding, but audits of their financial data suggest that they will have inadequate funds to actually cover that cost.

| Coal Companies’ Reclamation Obligations (From SEC filings, as of Dec. 31, 2014) | |||||

| Self-bonding | Surety bonds | Bank guarantees | Letters of credit | Total | |

| Peabody Energy | $1,361,400,000 | $325,200,000 | $319,800,000 | $17,600,000 | $2,024,000,000 |

| Alpha Natural Resources | $676,100,000 | $399,000,000 | $212,200,000 | $1,287,300,000 | |

| Arch Coal, Inc. | $458,513,000 | $177,714,000 | $3,500,000 | $639,727,000 | |

| Cloud Peak Energy | $200,000,000 | $448,900,000 | $648,900,000 | ||

| Total: | $2,696,013,000 | $1,350,814,000 | $319,800,000 | $233,300,000 | $4,599,927,000 |

Even regulators in typically coal-friendly states like Wyoming and West Virginia are questioning companies’ abilities to cover reclamation costs and their subsequent eligibility for self-bonding. A recent agreement between Alpha Natural Resources, in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings, and the state of Wyoming demonstrates the hazards of the practice. After being declared ineligible to self-bond by Wyoming, and being unable to post a surety or collateral bond, Alpha agreed to give the state a million “superpriority claim.” It would allow Wyoming to get $61 million in the event Arch’s assets are liquidated in bankruptcy. The agreement allows Alpha to continue mining in Wyoming even though more than $350 million in reclamation costs are now covered by neither a self-bond nor a superpriority claim.

Moreover, there is no requirement that a company’s promise to pay for such costs in the form of a self-bond will get any higher priority than the claims of other creditors on its assets. Frequently, the same assets that are used to signify the health of a subsidiary for self-bonding purposes are also used as collateral to take on debt by its parent company. They are in a sense “double-pledged.” The difference between the pledges, however, is that the parent company’s creditors have claim to the assets in the event of a bankruptcy whereas the regulatory agency does not. DOI and OSMRE should update self-bonding eligibility requirements and eliminate loopholes that let companies escape their financial obligations.