On Wednesday, March 16, the House Agriculture Committee held its fifth farm bill reauthorization hearing. The title? “A 2022 Review of the Farm Bill: The Role of USDA Programs in Addressing Climate Change.”

Do current farm bill programs address climate change? Yes, some. Conservation programs that promote grasslands and wetlands protection, for instance, can sequester carbon. However, when some of these programs, such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) were created in the 1980s, their intent was to reduce soil erosion and take land out of production. They weren’t created to address climate change. In fact, the 2018 farm bill mentioned the word “climate” and “climatological” just 10 times. And only a few of these reference global climate change, dealing with biomass use.

This needs to change. Climate change is having a clear and obvious effect on agriculture, a point many of the witnesses reiterated. Whether it’s more frequent or more severe droughts, floods, and hurricanes, this “increased weather volatility” has contributed to market volatility, presenting a challenge to profitability for farmers and ranchers. It has also led to increasing costs to taxpayers that subsidize the farm financial safety net.

As a whole, the overall farm safety net discourages investment in smart conservation practices that promote climate and financial resilience. Studies have found that the federal crop insurance program “can serve as a disincentive for climate change adaptation in agriculture,” discouraging the uptake of cover crops and making it financially viable for producers to plant in risk-prone areas at taxpayer expense. Crop insurance and ad hoc disaster aid programs are not inherently designed to promote resilience in the face of economic downturns and/or disasters, but rather distribute post-disaster payments. Just crop insurance and disaster aid alone cost taxpayers more than $10 billion per year on average, not to mention commodity and other farm bill programs that are similarly ill-positioned to address climate change.

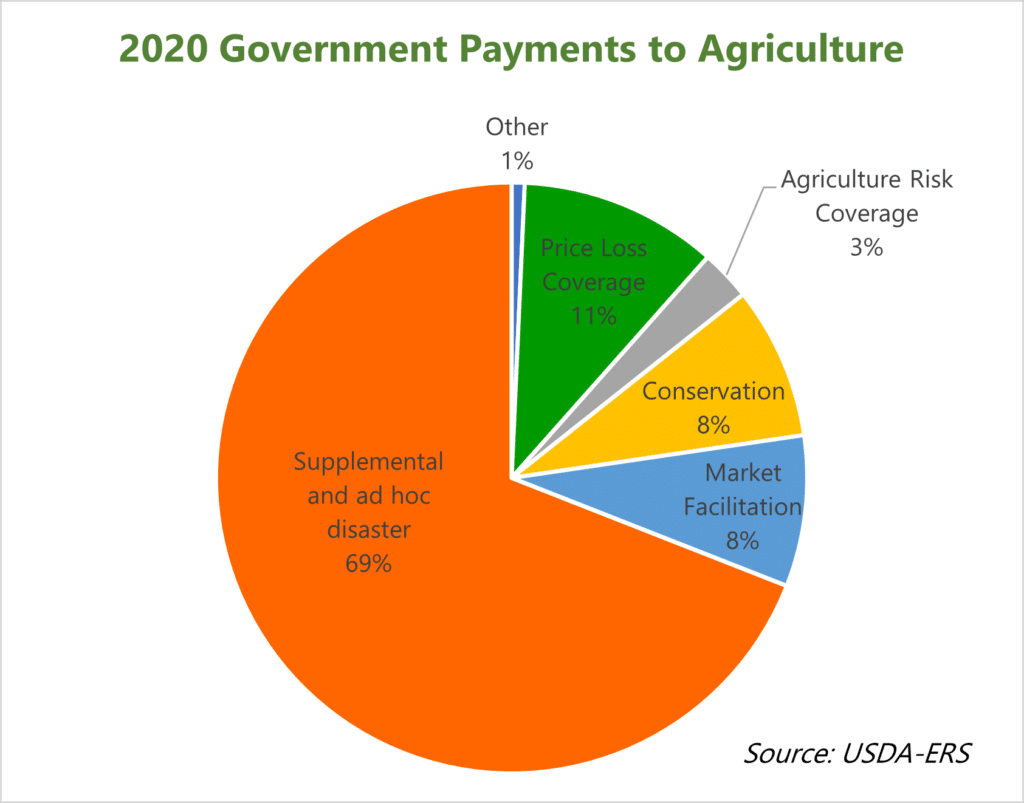

The farm bill does include a Conservation Title that promotes the adoption of practices that can benefit the climate (such as rotational grazing, grassed buffers, etc). CRP, plus working lands programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), fall into this category. However, conservation funding pales in comparison to programs promoting commodity production (such as Price Loss Coverage government-set payments and Agriculture Risk Coverage shallow loss subsidies), ad hoc disaster aid, and other after-the-fact financial supports. Conservation programs can also be reformed to make climate change mitigation an explicit resource concern, in addition to existing concerns, to better promote climate beneficial practices that also improve water quality, reduce nutrient loss, or achieve other important goals. Programs can also be improved to prioritize practices that deliver more bang for taxpayers’ buck.

The figure below, derived from US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS) data, shows that conservation programs made up just eight percent of government payments to agriculture in 2020. The figure does not even include federal crop insurance benefits to farmers, which totaled more than $5 billion that year. In other words, programs promoting agricultural production far outweigh investments in conservation programs/practices.

With the farm bill as a whole failing to promote taxpayer and farmer-friendly climate outcomes (with some programs working at cross purposes with one another), USDA and Congress are beginning to take steps to improve agriculture’s ability to address climate change. USDA is currently accepting applications for a new Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program that will use Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) funding to subsidize relevant projects throughout the US. Proposals to increase conservation spending, and direct at least some of it toward water and climate initiatives, were included in Build Back Better, the currently-stalled reconciliation bill. While we’ve expressed numerous concerns about USDA going on its own to fund climate projects (a double-whammy of CCC funding being used without Congress’s approval or guidance), some proposed reforms in Build Back Better could have benefits for taxpayers, the climate, and farmers alike.

However, a farm bill with tens of billions in status quo subsidies for industries and producers who often don’t need them, not to mention more wasteful subsidies for bioenergy, will fail to benefit the climate. The entire farm bill needs to be rethought if the goal is resilience, instead of dependence on federal subsidies. Mitigating the effects of climate change does not need to be the sole focus of every farm program. But farmers and taxpayers can’t afford for lawmakers to ignore the reality climate change is producing on the ground. A stable and predictable safety net that promotes economic resilience takes more than dollars, it also requires change.