This week, the House Agriculture Committee held its second hearing in preparation for the 2023 farm bill. The topic was “A Hearing to Review Farm Policy with Undersecretary Robert Bonnie.” As we wrote last week, the 2023 farm bill is a prime opportunity to reorient the current broken farm safety net toward a path of promoting resilience, instead of dependence on federal subsidies.

While parts of the hearing were devoted to reviewing various federal farm policies, a majority of it actually focused on a single proposed policy—the $1 billion Partnerships for Climate Smart Commodities that was announced by the Secretary of Agriculture on Monday. Democrats mostly lauded the Secretary’s announcement, while Republicans implored the USDA to focus on rising input prices, criticized various Biden Administration regulatory changes, and questioned the need for the new Partnership, as farmers “are already climate heroes” (Rep. Allen R-GA). For our initial take on this program—we are still reviewing the details—see our post here.

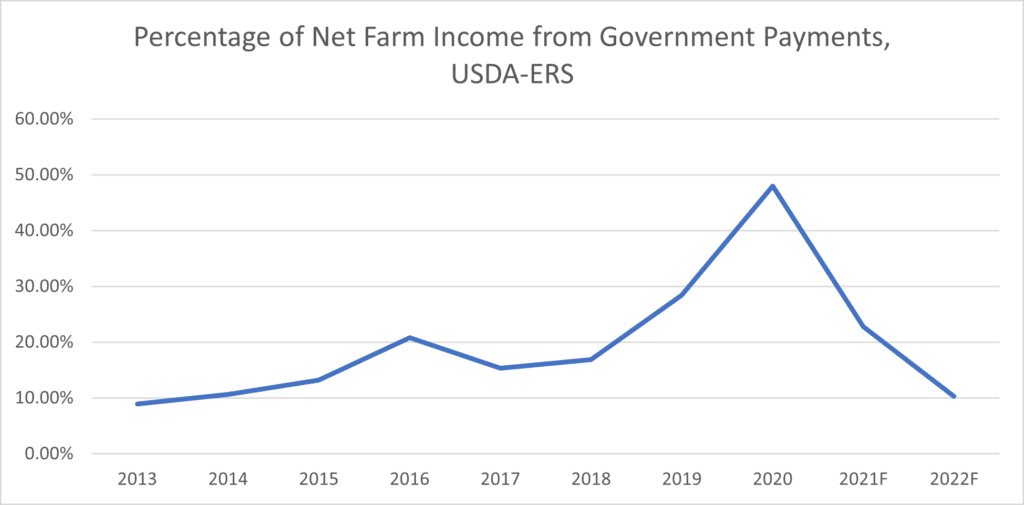

Noticeably absent from the hearing was a discussion of the role federal farm program payments play in efforts to improve (or not) the financial resilience of the agricultural sector. Federal agriculture payments rose to a record level in 2020 – $47 billion – primarily due to the pandemic, but ad hoc “emergency” disaster aid and farm bill subsidies also played a hand. Federal subsidies made up nearly one of every two dollars of farm income in 2020. Overall payments fell to $27 billion in 2021, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS), but still exceeded historical averages. On Friday, the USDA-ERS released a new farm income update, estimating 2022 payments of $12 billion, which would be more in line with historical averages. As this figure shows, government payments would make up around 10 percent of farm income, which should be seen as good news for taxpayers and others looking to promote resilience not dependence on federal farm subsidies.

With net farm income expected to reach $114 billion in 2022 – the second-highest level in a decade – most parts of the agriculture sector have rebounded well from the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, some industries such as soybeans fared better in 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on the economy and markets. In response to the pandemic, Congress authorized tens of billions of dollars in COVID-19 payments, with the USDA chipping in another $6.5 billion. Most of this spending has already gone out the USDA’s door but more for biofuels and other interests is still on the way. The USDA expects the final $3.4 billion in payments to be spent in 2022.

In addition to COVID-19 aid, producers benefit from a generous farm safety net comprised of permanent disaster programs, commodity supports, federal crop insurance subsidies, and others. On top of this, Congress authorized $16 billion in the last handful of years for “emergency” ad hoc disaster aid despite some producers’ incomes already being propped up (and crop losses insured) by both private and highly subsidized federal insurance. To put it lightly, the level of current subsidization coming from Washington is unnecessary. Don’t take our word for it. Nebraska farmers that we’ve recently talked to agree, as do others across the country.

The current farm safety net influences producers’ planting decisions, distorts markets, and simply costs too much money for federal taxpayers. Programs like crop insurance encourage risk taking at taxpayer expense while failing to encourage the adoption of smart conservation practices (such as cover crops, no till, grassed buffers, rotational grazing, etc.) that promote resilience in the face of climate risks and economic challenges.

To achieve a farm bill that improves outcomes for both taxpayers and consumers – instead of special interests – Congress should implement the following principles in the 2023 farm bill:

- Cost-effective: Eliminate programs that don’t work and subsidies that cause long-term liabilities and unintended consequences for our air, soil, water, and climate. Prioritize investments in programs that deliver the best bang for taxpayers’ buck.

- Equity: Long gone should be the days of farm bill programs benefiting large and/or wealthy individuals and landowners who don’t need them. Subsidies for confined animal feeding operations and other examples of waste, fraud, and abuse should be eliminated. Finally, socially disadvantaged, new, beginning, and small farmers’ interests should not take a back seat to special interests or the farm lobby.

- Accountable: Smart conservation practices that help farmers help themselves should be incorporated into the farm bill holistically instead of in a piecemeal fashion. Promoting climate and economic resilience in crop insurance in particular can ensure taxpayer dollars are spent wisely, insurance rates better reflect real risk, and producers are incentivized to utilize risk reduction strategies that increase profits and build long-term economic viability.

- Transparent: Information about all farm bill supports should be publicly available online in an easy to understand, searchable format so programs can be evaluated on their merit. Concerns about individuals’ privacy need not be a hindrance to better transparency.

- Responsive: The federal government’s role in agriculture should be to only step in during times of true need (such as deep, widespread drought), not layering duplicative payments on top of one another and/or guaranteeing high levels of income, causing moral hazard and other negative impacts. Congress should focus on reforming crop insurance to promote climate resilience and better water quality, for instance, instead of creating new programs that dispense payments for post-disaster losses. Reining in misuse of the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) should also be a priority to ensure Congress has an adequate say in how taxpayer dollars are spent.