View/Download this article in PDF format.

The 2014 farm bill created new income entitlement programs for agribusinesses, referred to as “shallow loss” subsidies. The three programs – Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC), Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO), and Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) – are intended to kick in when revenue drops as little as ten percent from a predetermined level. (See Appendix 1 for a comparison of the programs.) They are designed to sit on top of and function as add-ons to federally subsidized crop insurance, a highly subsidized program that already covers crop revenue shortfalls of as little as 15 percent. Shallow loss programs are essentially “insurance for crop insurance” – designed to eliminate the small “deductible” required under crop insurance policies. The combination of lucrative subsidies, designed to essentially eliminate financial risk for agricultural producers, is something no other industry enjoys. Shallow loss programs primarily benefit corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton – crops that have been heavily subsidized by the federal government for decades – while over sixty percent of farmers receive no government subsidies at all.

Shallow Loss Subsidies May Surpass Cost of Direct Payments

Agricultural economists estimate that shallow loss programs may end up costing taxpayers more than the direct payment program they were intended to replace. Nearly everyone – including farmers – agreed that direct payments—subsidies paid to owners of land whether they grew crops or not – needed to be eliminated, yet Congress created three new complicated programs in their place.

- Unlimited subsidies cost taxpayers more: While direct payments cost taxpayers about $5 billion each year, shallow loss subsidies are unlimited, meaning if yields or prices decline from near record heights (which they’ve done recently), the programs could cost taxpayers double or triple the cost of direct payments. A study led by Montana State economist Vincent Smith estimated that shallow loss programs could cost $8-14 billion per year – or about two to three times the cost of direct payments – over the next few years.

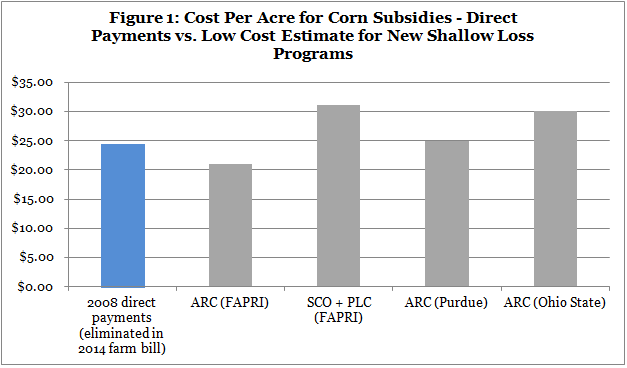

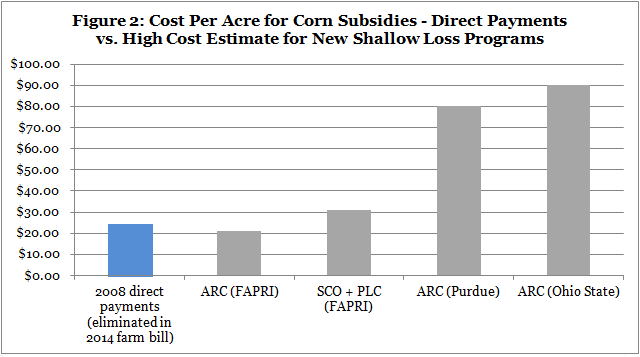

- Higher costs per acre: The Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) estimates that all seven major commodities – except rice – will receive higher subsidies through the combination of government-set minimum price supports (known as Price Loss Coverage, or PLC) and SCO than would have occurred with direct payments. However, FAPRI predicts per-acre ARC payments will be less than direct payments, except for barley and soybeans. An additional analysis by Purdue University estimates per-acre shallow loss subsidy payments will surpass direct payments, even tripling the cost of direct payments if corn prices drop to $3.50 per bushel. See Table 1 for more information.

| Table 1: Per-Acre Subsidy Payments of Direct Payments Versus Shallow Loss Programs (net of crop insurance premium costs) | ||||||||

| Average Subsidy Payments/Acre | Corn | Wheat | Soybeans | Upland Cotton | Sorghum | Barley | Rice | Peanuts |

| 2008 direct payments (eliminated in 2014 farm bill) | $24.39 | $15.21 | $11.54 | $33.86 | $16.87 | $9.68 | $96.25 | $45.85 |

| ARC (FAPRI) | $20.91 | $9.84 | $16.21 | $8.16 | $10.76 | $8.44 | $19.76 | |

| SCO + PLC (FAPRI) | $31.18 | $20.11 | $17.67 | $22.76 | $34.64 | $66.44 | $60.63 | |

| STAX (FAPRI) | $22.60 | |||||||

| ARC (Purdue) | $25-$40 with $3.75/bushel & $55-$80 with $3.50/bushel price | $20-$30 with $10/bushel & $40-$60 with $9.40/bushel price | ||||||

| ARC (Ohio State) | $30-$90 with $3.60/bushel price | |||||||

| * The cost of shallow loss programs range anywhere from slightly less than direct payments to three times as costly for corn and five times as costly for soybeans. | ||||||||

Other Taxpayer Concerns with Shallow Loss Programs

Aside from their potential huge taxpayer cost, shallow loss subsidies raise numerous other taxpayer concerns, including the following:

- Benefit the largest agribusinesses: In the 2008 farm bill, producers were limited to $40,000 in direct payments annually. The 2014 farm bill took a huge step backward increasing this limit to $125,000 for commodity subsidies (ARC/PLC), in addition to unlimited SCO, STAX, and crop insurance subsidies. A modest 15 percent reduction in crop insurance premium subsidies and STAX/SCO subsidies, which passed the full Senate in both the 2012 and 2013 farm bills, was stripped from the final 2014 farm bill at the last minute behind closed doors; in addition, the overly generous commodity subsidy limitation of $125,000 was greatly increased from the original $50,000 limitation in the 2013 Senate farm bill. These high payment limitations benefit the largest agribusinesses at the expense of beginning farmers and small and mid-sized farmers. In 2012, the average farm received $10,000 in subsidies while the largest producers received six times this amount. This disparity will only grow with time.

- Lock in record profits: High commodity prices, partially caused by government mandates and subsidies for the corn ethanol industry, led to record farm income over the past seven years. Shallow loss programs are designed to lock in these record levels and make subsidy payments when yield or prices dip slightly instead of covering deep losses from severe droughts or floods. To illustrate how high guaranteed incomes are, in 2012, the average farm profited $37,000 while farms with more than 2,000 acres earned over ten times this amount – $371,000.

- Subsidize producers for crops they aren’t growing: Similar to direct payments, ARC makes subsidy payments on base acres, or a maximum number of crop acres farmers used to grow. The 2014 farm bill allows producers to “reallocate” their base acres, so crops can be shifted as long as the total acres do not exceed their historic “base” acreage. For example, “a farm could be planted to alfalfa but could possibly collect a corn ARC payment if revenue drops enough to trigger it.” In other words, taxpayers will continue to subsidize farmers for crops they aren’t currently planting.

- Subsidize producers for fake losses: Since payments in some shallow loss programs are triggered by calculations on average production in a county, an individual producer may not have actually lost crops or revenue but still receive government subsidies.

- Crowd out private sector risk management options: Because shallow loss programs subsidize small dips in income that agribusinesses can weather without federal subsidies, new, innovative, and unsubsidized private sector risk management options are crowded out of the marketplace. With a growing national debt, now more than ever, the government should reduce interventions into the agriculture sector.

- Create a conflict of interest: Since crop insurance agents earn commission when a crop insurance policy is sold, incentives exist to encourage producers to enroll in SCO versus the government-run ARC.

- Create special interest carve-outs: While seven crops – corn, cotton, grain sorghum, rice, soybeans, barley, and wheat – are currently eligible for SCO subsidies and these and an additional four – oats, pulse crops, other oilseeds, and peanuts – are eligible for ARC, STAX solely subsidizes the cotton industry. Historically, the big five crops – corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice – received the bulk of federal farm subsidies, and the 2014 farm bill continues this practice, in addition to creating several other crop insurance carve-outs for special interests.

- Complicate producers’ decisions: Per the 2014 farm bill, producers must make a one-time decision between enrolling in ARC or PLC (with the additional option of annually choosing to participate in SCO); the latter is the default if a producer fails to sign-up for one program or the other. However, wheat producers can change their mind without paying a penalty, and since producers won’t sign up for 2014 farm programs until 2015, they will be able to maximize subsidy payments having known market conditions prior to sign-up. This decision and the underlying programs are so complicated that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is spending $6 million to tell producers which option will result in the highest subsidy payments.

- Reduce public transparency: The recipients of at least two shallow loss programs – STAX and SCO will be shielded from the public eye unlike direct payments and ARC which were/are subject to public disclosure.

- Subsidize the riskiest farmland: Since producers on average pay 38 cents for every dollar of their crop insurance coverage (available from 50 to 85 percent coverage), they have an incentive to enroll riskier land in higher coverage levels. In particular, the riskiest farms will likely enroll in SCO to guarantee high levels of revenue each year (SCO is 65 percent taxpayer-subsidized – see Appendix 1 for more information). Taxpayer-subsidized payouts and premium subsidies will benefit producers in disaster-prone areas, such as growing corn in dry areas of western Kansas. Kansas State University economist Art Barnaby estimates that producers in low-risk counties will continue to purchase higher levels of popular revenue protection crop insurance coverage while producers in high-risk counties, where low-cost subsidized crop insurance policies at the highest levels of guarantee (80 to 85% of revenue) are not available, will enroll in SCO.

- Shift more risk onto taxpayers: the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that producers will drop crop insurance coverage levels with the availability of fully or highly subsidized shallow loss programs, ultimately resulting in more financial risks shifted onto taxpayers instead of producers assuming normal risks of doing business. Since ARC, STAX, and SCO are subsidized at 100, 80, and 65 percent, respectively, producers may forgo enrolling in the highest crop insurance coverage levels (up to 85 percent), which is 38 percent subsidized, and instead opt for more highly subsidized options. As of the 2014 farm bill, producers can sign up for catastrophic insurance, or coverage guaranteeing 50 percent of annual yield, in addition to the SCO add-on, which then guarantees 50 to 86 percent of yield or revenue, the former subsidized at 100 percent and the latter subsidized at 65 percent instead of lower subsidy levels.

- Distort planting decisions: Crop insurance, STAX, and SCO subsidies are based on planted acreage, meaning they increase as producers farm more acres. While new accountability provisions require conservation of highly erodible land and wetlands in exchange for these subsidies, taxpayers still subsidize the conversion of sensitive land to cropland.

Conclusion

Estimates that new shallow loss programs will cost billions more than promised should cause Congress to reconsider their authorization. While the entire farm safety net should be made more cost-effective, transparent, accountable, and responsive to current market conditions, these goals particularly apply to shallow loss entitlement programs. Targeting subsidies only to those experiencing real, deep, and unforeseen losses instead of propping up income for the most profitable agribusinesses every year would be a good first step toward making farm subsidy payments more accountable to taxpayers.

For more information, please contact Josh Sewell at josh [at] taxpayer.net or 202-546-8500.

* For a comparison chart of new shallow loss programs in the farm bill, please download the full fact sheet here.