Tax policy has emerged as one of the few areas that both political parties agree needs considerable reform.

Over the years, the nation’s tax code has become littered with increased complexity, parochial tax treatments, and revenue giveaways that must be curtailed. Lawmakers must address the profusion of specialized tax breaks that cost taxpayers more than $1 trillion in revenue every fiscal year.

With tax day around the corner and in the middle of a heated debate on the extension of dozens of annually renewed tax expenditures, the need for comprehensive tax reform has once again become front and center. Earlier this year and late last year both the House, under Chairman Camp and the Senate, under Chairman Baucus, released comprehensive tax reform proposals and while dramatically different, it is notable that both address billions of dollars in oil and gas subsidies provided through the tax code.

How Republicans Should Approach Revenue Neutrality for Real Tax Reform

Lawmakers will only worsen our budget problems by simply cutting taxes and calling it reform.

Ever since the last major overhaul of the tax code in 1986, politicians across the political spectrum have sung the praises of reform that is revenue neutral. Revenue-neutral reform means there would be changes in rates and policies, but the amount of revenue raised by the overall tax system would remain the same. Some left-leaning think tanks and politicians insist that our more-than-a-decade-long spree of deficit spending, despite the efforts to restrain spending through the Budget Control Act and its successor agreements, suggests that we need more money rather than the same amount. But revenue neutrality has remained a core principle for the Republican Party.

Subscribe to our Weekly Wastebasket to see how we’re tracking your tax dollars!

How does one achieve revenue neutrality? There are two ways, both of which bring political pitfalls. The first is perhaps the most obvious: lowering rates while also eliminating or curbing tax expenditures (i.e. exclusions, credits, exemptions). This “base broadening,” the argument goes, would offset the cost of lower rates. In the abstract, this sounds good. But it turns out many of the people and companies whose taxes would go up under a new system, like oil and gas companies, tend to be well represented by lobbyists protecting those loopholes. To be sure, many tax expenditures should be eliminated. If Congress wants to subsidize an industry or an activity, it should allocate the money through the annual budget process, not create a special, permanent tax status – this is why the tax code is such a mess. Read more ▻

Tax Reform Turns 30

On October 22, it will have been 30 years since Congress and the president came together to tackle tax reform. Yet, there is a rare consensus that the federal tax code must be overhauled, and even bipartisan agreement on specific reforms.

One area of agreement is corporate taxes. Corporate tax policy is hurting U.S. competitiveness and economic growth. Productivity growth, workforce participation, and median household income have been on the decline since the late 1990s. Increasing globalization has intensified the problems with our corporate tax code, particularly the high U.S. corporate tax rate and our system of taxing international income. Not only is reforming the tax code critical to improving U.S. competitiveness, it is essential to achieving a sustainable federal budget.

The path forward begins with Congress and the next president spending some political capital on bringing about meaningful reform. Without Congress, presidential tax reform plans are political documents – useful in telling us where a candidate stands in the broadest terms, but meaningless in the sense that they don’t tell us how changes will actually be paid for and how they will affect the long term deficit and debt. And no matter how detailed an outline, things don’t get serious until a lawmaker actually puts a proposal into legislation and receives a budget score from the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office. And, as we learned in 1986, the president has to keep the focus on getting it done. Read more ▻

Additional Material on Tax Reform

Reform the Tax Code

Report

September 2016

The U.S. tax code last underwent a major overhaul 30 years ago.

Today, it is a confusing thicket of narrow carve-outs, parochial preferences, and revenue giveaways. As problems with the existing code and annual tax extenders packages continue to mount, the need for reform grows. Whatever the path tax reform takes in the years ahead, it is clear it will be a challenging endeavor. But, as history shows us, even though tax reform has never been easy, it can be done.

TCS Responses to Recent Tax Reform Proposals

Breakdown of Rep. Camp’s Tax Reform Proposal

TCS analysis and commentary on the draft tax reform proposal released by Rep. Dave Camp. Even though most observers believe it will not receive a vote this year, this draft is a marker that can jumpstart the debate instead of continuing abstract discussions about individual tax breaks or the preferred top rate.

Letter to Chairman of Senate Finance Committee Re: Tax Reform Discussion Drafts, January 14, 2014

A detailed response to the proposals set forth in the discussion drafts released by Sen. Baucus. Many of the proposals would begin to remove unnecessary favoritism for certain corporate taxpayers, reduce the number of distortions in the tax code overall, and create more certainty with regard to international taxation.

Tax Reform for the Oil & Gas Industry

Taxpayers for Common Sense’s new report, Understanding Oil and Gas Tax Subsidies, offers a detailed review of the suite of subsidies the oil and gas industry receives. While industry proponents claim the oil and gas industry does not receive special treatment in the tax code, several century-old breaks sit on the books solely for oil and gas development.

Report: Understanding Oil and Gas Tax Subsidies

TCS takes on the claim that oil and gas companies pay high federal tax rates and evaluates seven tax treatments and accounting gimmicks for oil and gas companies. A century ago, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution established Congress’s ability to impose individual and corporate income taxes. Just a few years later the oil and gas industry got their first tax breaks and the subsidies for this industry have been with us ever since. In fact, over the years as changes were made to the code, new breaks or “tax expenditures” were added.

Download the Full Report here (pdf)

Infographic: A Century of Subsidies for Big Oil

Recommendations for Reform

Domestic Production Activities Deduction (Section 199): Ineffective Tax Policy

.jpg) The domestic production activities deduction provided under Section 199 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is a poorly-targeted policy that creates inefficiency in the tax code while draining resources from other job-creating investments or broader tax reductions. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the production activity deduction will result in $78.2 billion of forgone tax revenue for the years 2013 through 2017.

The domestic production activities deduction provided under Section 199 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is a poorly-targeted policy that creates inefficiency in the tax code while draining resources from other job-creating investments or broader tax reductions. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the production activity deduction will result in $78.2 billion of forgone tax revenue for the years 2013 through 2017.

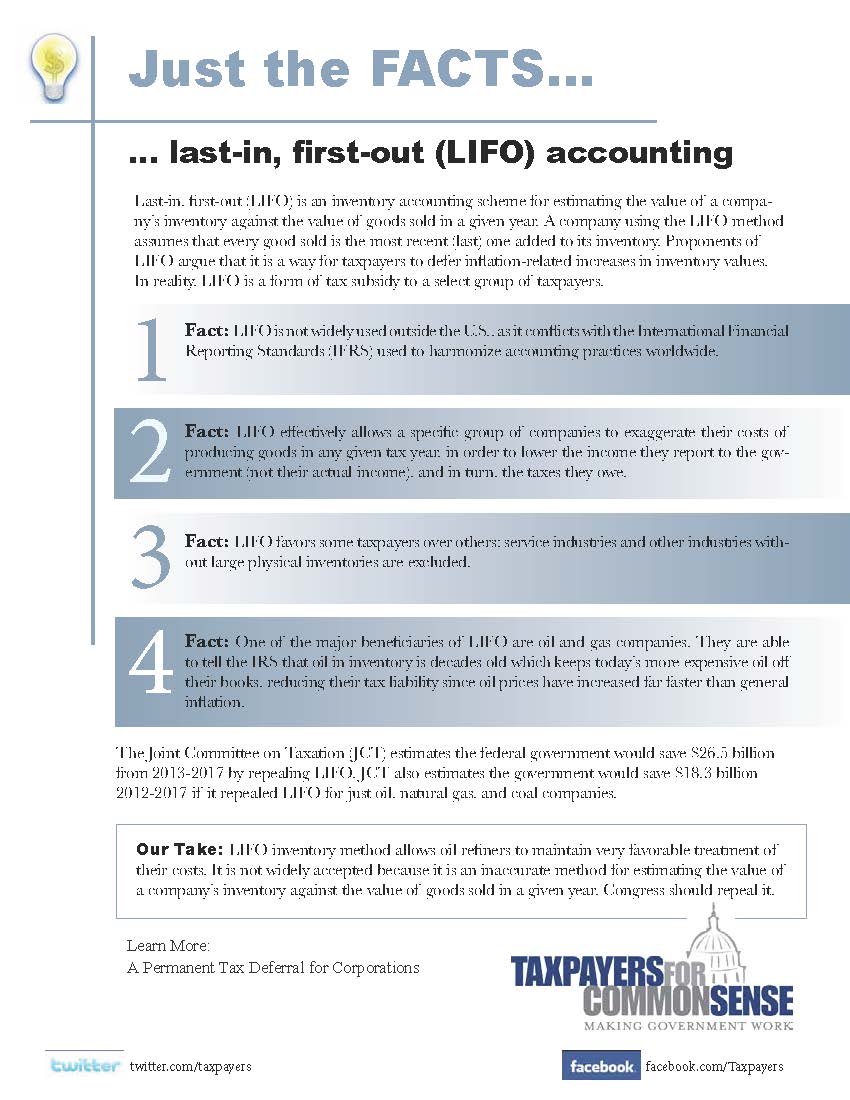

Last-In, First-Out Accounting: Permanent Tax Deferral for a Select Group of Taxpayers

Last-in, first-out (LIFO) is a method for estimating the value of a company’s inventory against the value of goods sold in a given year. LIFO makes the federal tax code more inefficient by encouraging the accumulation of inefficient levels of inventories over other capital investments. It favors some taxpayers over others. LIFO is not widely used outside the U.S., as it conflicts with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) used to harmonize accounting practices worldwide. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates the federal government would save $26.5 billion over the next 5 years by repealing LIFO.

Last-in, first-out (LIFO) is a method for estimating the value of a company’s inventory against the value of goods sold in a given year. LIFO makes the federal tax code more inefficient by encouraging the accumulation of inefficient levels of inventories over other capital investments. It favors some taxpayers over others. LIFO is not widely used outside the U.S., as it conflicts with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) used to harmonize accounting practices worldwide. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates the federal government would save $26.5 billion over the next 5 years by repealing LIFO.

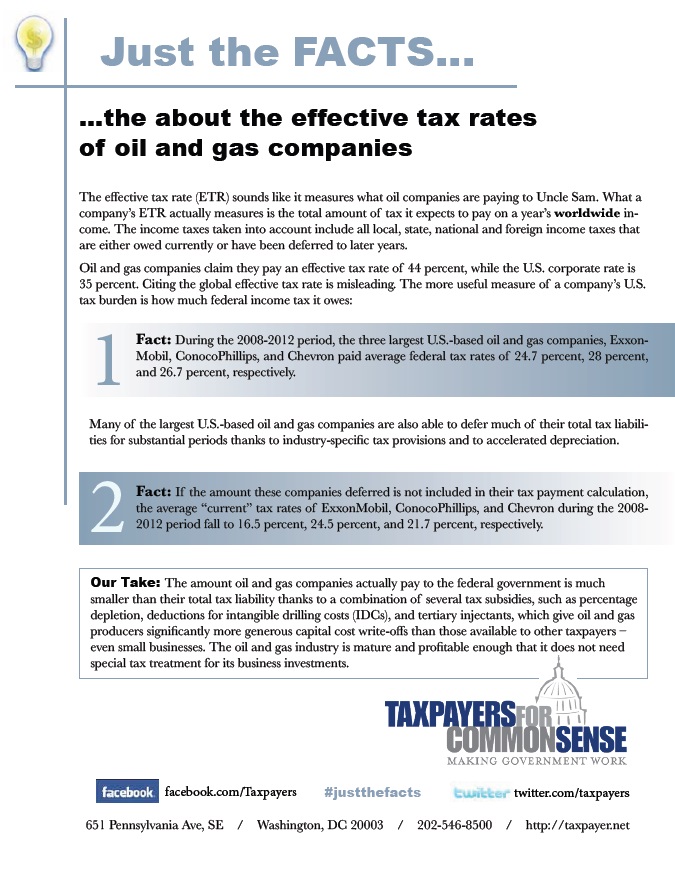

The Effective Tax Rates of Oil and Gas Companies

The effective tax rate (ETR) sounds like it measures what oil companies are paying to Uncle Sam. What a company’s ETR actually measures is the total amount of tax it expects to pay on a year’s worldwide income. The income taxes taken into account include all local, state, national and foreign income taxes that are either owed currently or have been deferred to later years.

The effective tax rate (ETR) sounds like it measures what oil companies are paying to Uncle Sam. What a company’s ETR actually measures is the total amount of tax it expects to pay on a year’s worldwide income. The income taxes taken into account include all local, state, national and foreign income taxes that are either owed currently or have been deferred to later years.

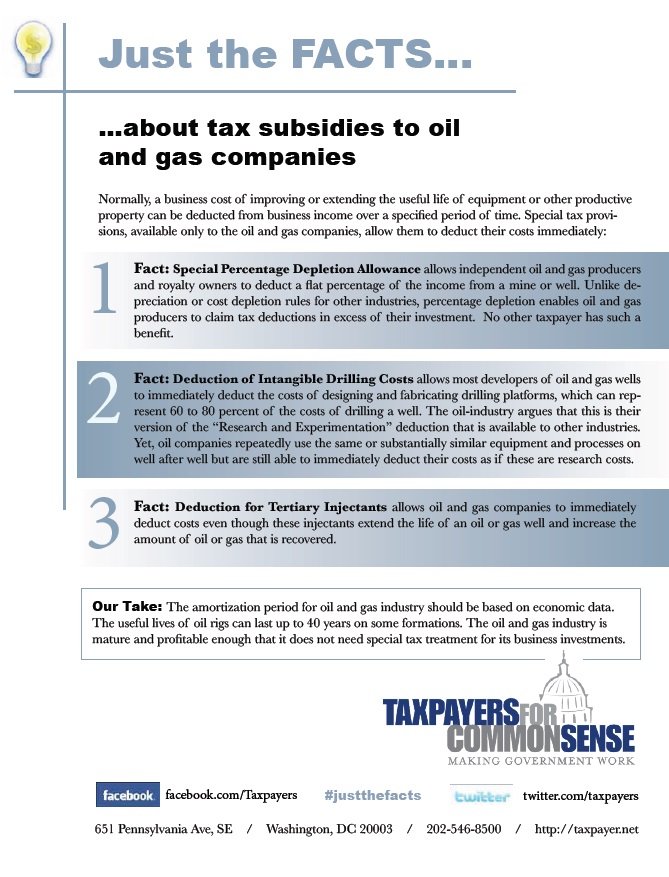

Tax Subsidies to Oil and Gas Companies

Normally, a business cost of improving or extending the useful life of equipment or other productive property can be deducted from business income over a specified period of time. Special tax provisions, available only to the oil and gas companies, allow them to deduct their costs immediately.The amortization period for oil and gas industry should be based on economic data. The useful lives of oil rigs can last up to 40 years on some formations. The oil and gas industry is mature and profitable enough that it does not need special tax treatment for its business investments.

Normally, a business cost of improving or extending the useful life of equipment or other productive property can be deducted from business income over a specified period of time. Special tax provisions, available only to the oil and gas companies, allow them to deduct their costs immediately.The amortization period for oil and gas industry should be based on economic data. The useful lives of oil rigs can last up to 40 years on some formations. The oil and gas industry is mature and profitable enough that it does not need special tax treatment for its business investments.

Other Tax Reform (Tax Extenders)

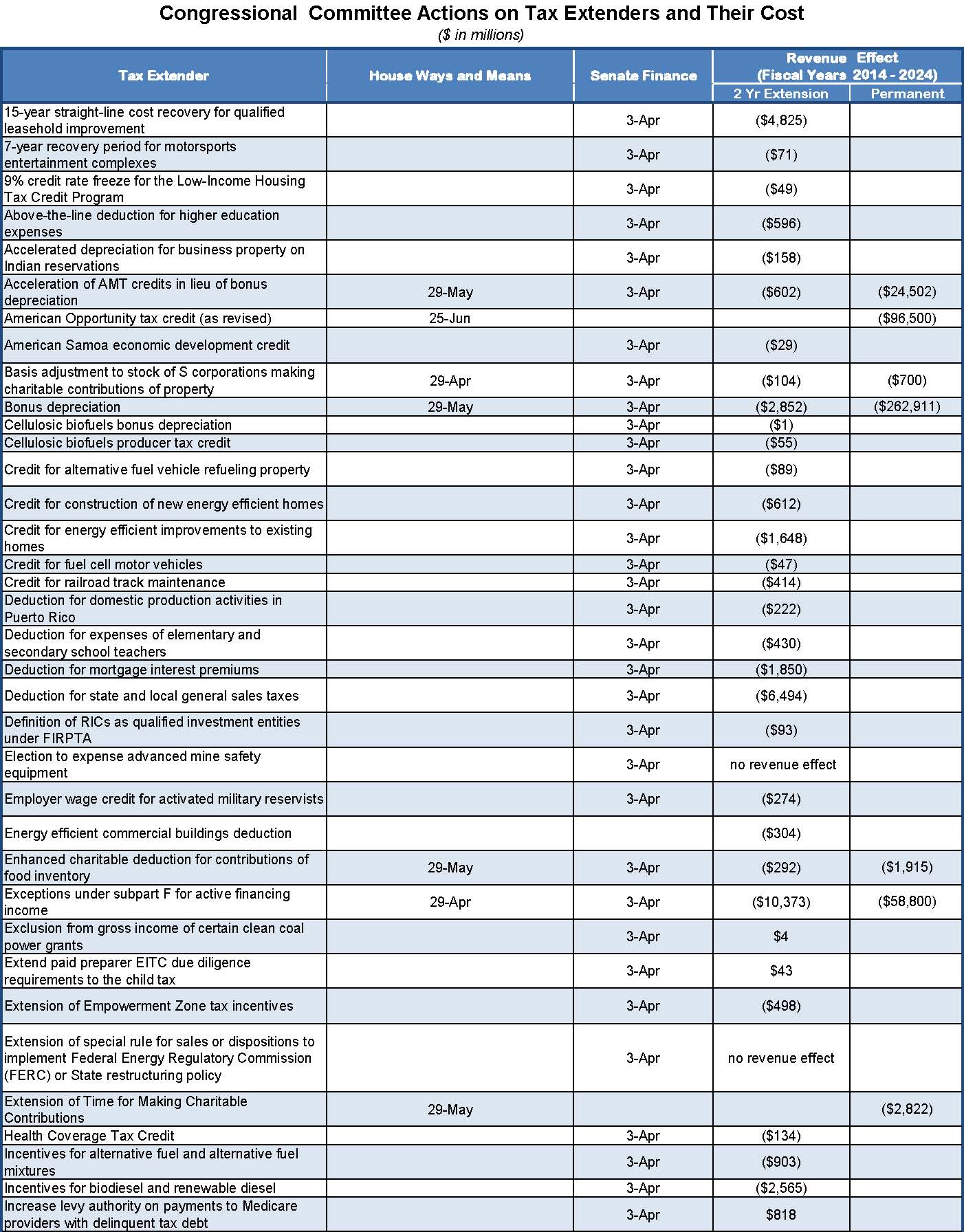

Tax extenders are a hodge-podge of generally narrow interest tax expenditures (breaks) that are only authorized for a year or two at a time, but as you can see they often hang on for years, never being incorporated into the tax code and rarely being investigated thoroughly for their effectiveness.

They range from benefits for NASCAR track owners, to write offs for race horse owners, from subsidies for film and television production to tax breaks for alternative fuels and biodiesel.

Beneficiaries of these tax extenders include Liquor Companies Capitan Morgan and Bacardi

Tax Extenders were included in the 2008 Economic Bailout

Tax Extenders in the 2010 tax bill

Top 10 Tax Fails of the 2012 Fiscal Cliff

Congressional Actions on Tax Extenders in 2014 – Chart

Congressional Actions on Tax Extenders in 2014 – Chart

- Also available for download in XLSX format