The Biden Administration has said it is throwing everything at tackling inflation. And it is quite clear that it is not going to be solved by quick fixes. TCS President Steve Ellis and Senior Policy Analysts Josh Sewell and Wendy Jordan spell out how Congress and the administration can remove federal policies distorting the playing field for the benefit of special interests and driving up costs for taxpayers.

Listen here or on Apple Podcasts

Episode 23 – Transcript

Intro:

Welcome to Budget Watchdog All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending, and tax issues facing the nation. Cut through the partisan rhetoric and talking points for the facts about what’s being talked about, bandied about, and pushed to Washington. Brought to you by Taxpayers for Common Sense. And now, the host of Budget Watchdog AF, TCS president Steve Ellis.

Steve Ellis:

Welcome to All American Taxpayers Seeking Common Sense. You’ve made it to the right place. For over 25 years. TCS, that’s Taxpayers for Common Sense, has served as an independent, nonpartisan budget watchdog group based in Washington, DC. We believe in fiscal policy for America that is based on facts. We believe in transparency and accountability because no matter where you are in the political spectrum, no one wants to see their tax dollars wasted. And that is sadly why so often citizens and lawmakers alike look away when deep scrutiny is what is needed. Let me put it another way. If you’ve got car trouble and you take it to the mechanics with specific concerns, you want to hear if they found anything else of concern while they’re under the hood, right? Fixing only half the problem is a prescription for poor performance and future problems.

Steve Ellis:

Well, that is exactly where we, American taxpayers, are today when it comes to combating inflation. Cars up on the lift, the mechanics are working, but the view from the waiting room looks a whole lot like half the job is not getting done. So dear podcast listeners, we’re going to use this episode of Budget Watchdog, AF as an intervention. And with the help of my laser-focused colleagues, Wendy Jordan, and Josh Sewell, TCS Senior Policy Analyst both, we’re going to deliver a plan to help battle against inflation. It won’t all be swift, but it is necessary. At the Philadelphia AFL-CIO Conference this week, President Biden said he’s ready: “So, gas is up and food is up, which we’re going to get down, come hell or high water, but there’s other things we can do.”

Steve Ellis:

Wendy and Josh, are you ready?

Josh Sewell:

I was born for this.

Wendy Jordan:

Ha! Hang on Steve. I’m focusing my laser now.

Steve Ellis:

All right. Well then, away we go. Our hard to reach targets here are special interest carve outs, unnecessary parochial protectionist, and crony capitalist policies that drive up costs for consumers. Yes, we like alliteration at Taxpayers for Common Sense. Josh, the examples of federal favoritism we are about to reveal, don’t just hurt consumers, do they?

Josh Sewell:

No, Sir. They also increase costs for the federal government, while at the same time being counterproductive to actually achieving their stated policy goals. Now, eliminating counterproductive policies will take time to produce savings, but they will pay off in the long run. It also would increase opportunity and equity by reducing the power of special interest to tilt the playing field in their favor.

Steve Ellis:

So Josh, I guess a good example for the listeners of how certain policies can negatively affect consumers is one, I don’t think I ever contemplated talking about, and that’s baby formula. Explain how federal policies affected that recent shortage.

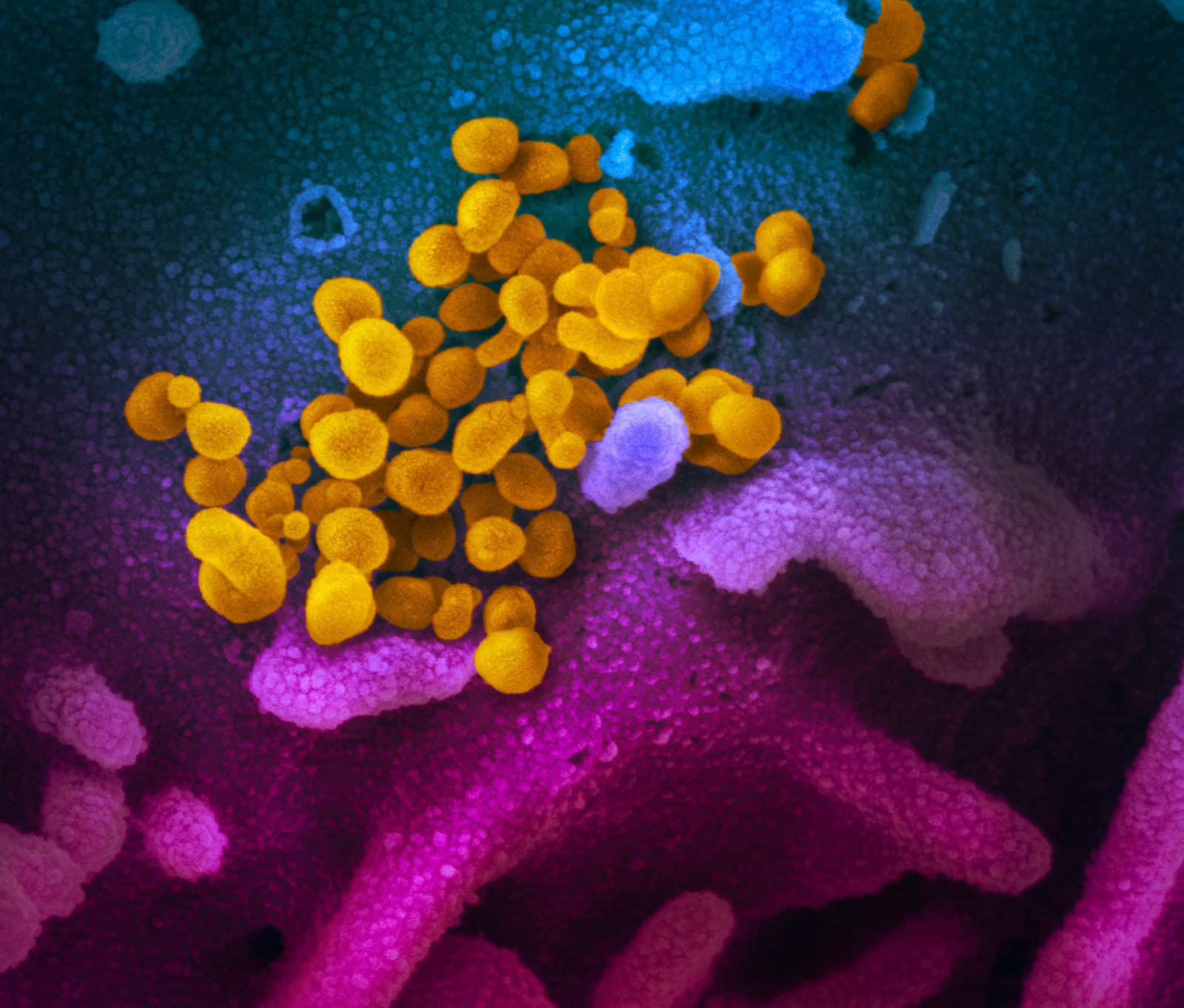

Josh Sewell:

Sure. So this is a real issue. There have been massive shortages in infant formula in the last few months, if you’ve been following the headlines at all. Now, let’s be clear that some of this is pandemic demand-related. So, supply chain disruptions are a part of the issue right now. And another big issue in the baby formula market is that it’s what we call fluctuating demand. So, you tend to hoard if you think you’re not going to have baby baby formula. So, there is a little bit of supply and demand issues, some pandemic issues, and as someone who has had four children themselves, I understand this quite personally.

Josh Sewell:

The immediate cause of the most recent problems in the baby food formula market, Abbott lab had a shut down with one of their major plants in Michigan because of unsanitary conditions. So, you had a tight market, you had a lot of people who have pent-up demand or who are very sensitive to supply shocks. And then you had a large plant shut down and all of a sudden, some amount of baby formula disappeared from the markets. So, the question is then, how would the market solve itself here? Well, in general, what happens when you don’t have domestic production of something? Does anyone know?

Steve Ellis:

Import?

Josh Sewell:

Exactly. So, if you can’t produce it domestically, you would import. It’s supply and demand. Lower supply, greater demand. Well, it’s not happening. And there’s a couple reasons why. The first is that much of our dairy policy is geared around preventing Canada, our good friends to the north, from actually exporting products to the US. So, there’s a whole complicated preexisting tariff rate quota system on all the kinds of products that you would get from milk. So, Canada is allowed to export X amount of full fat yogurt to the United States. More than that, slapped with a tariff. This goes across the dozens and dozens and dozens of products. And what is one product that turns out that comes from dairy? Often, it also comes from soy.

Steve Ellis:

Baby formula.

Josh Sewell:

Exactly. And so what you have right now is you have Canada as a potential supplier of baby food formula and other dairy-based products into the United States. However, the amount that they can send to the United States is restricted because of tariffs. And specifically when the Trump administration renegotiated NAFTA, they actually made it harder for Canadian companies to produce dairy-based infant formula and sent it to the United States. Essentially what they said is they created a certain level that they’re allowed to export. And every year they can only increase it by 1.2% each year. Clearly when a major plant shuts down in the United States, there’s going to be more than a 1.2% increase in demand.

Steve Ellis:

I think I saw something of those almost like Abbot makes 40% of the formula in some states. And there’s some other limitations as well. And so this renegotiation, that was the USMCA, right?

Josh Sewell:

That is, yeah. The USMCA is the rebranded NAFTA.

Steve Ellis:

Isn’t there an issue too, about how in certain states people on, is it on Medicaid can only buy formula from certain companies as well?

Josh Sewell:

Absolutely. So, there’s a program called the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. And that’s targeted towards infants, primarily and children who are under the five years of age and under who live at or below the poverty line, and up to a certain level above that. It’s a nutritionist assistance program to help impoverish people buy food. But under that program, using federal dollars that are then handed to the states, the states are allowed under that program to go on what’s called sole-source contracting agreements. So they go with one of the large, there’s basically four companies total that supply infant formula in the United States, which is in and of itself an issue of consolidation. But in these states, you can get the companies bid for these contracts so that they are the only provider that people who are using WIC money can purchase infant formula from.

Josh Sewell:

So, it wouldn’t matter how many companies were there. If you have a WIC voucher, you can only buy Similac or some other name brand from one of these companies. And that becomes an issue because, again, if your brand is not produced because of a supply chain issue, because of a health shutdown, that’s why the Abbott lab production facility in Southern Michigan was closed was because it was unsanitary and unhealthy. It wasn’t because of economics. It was because of conditions. Then, you don’t have anything you can buy. So, that becomes an issue of a monopolization and creating this artificial lack of supply because of a federal policy that allows states to do this. Now, there is a benefit from having a socialist contract. In that, these companies are basically, there was one study that showed that on average, they are providing WIC-purchased infant formula at 92% less than it would cost at a wholesale level. So, basically they’re giving a 92% discount. They’re losing a ton of money on this, but they’re losing a ton of money so that they can be the only person on the supermarket shelf, basically.

Steve Ellis:

Right. And they’re protected through these tariffs as well. It is a taxpayer group. I mean, we’re not anti-regulatory, but there needs to be smart policies in place to ease some of these provisions and to deal with some of these real world consequences of these policies. So, we talked a little bit about tariffs there, Josh, and there’s been some discussion about easing some of President Trump’s tariff bench, even on China. So, what’s going on there about tariffs and how does that affect inflation?

Josh Sewell:

If we remember back to the Trump administration, they started this trade war basically with China, but it is importantly, not just with China, with our European allies, and with Canada, and to a certain extent with Mexico before the USMCA was renegotiated. So, there are nearly 11,000 products or items in what’s known as the Harmonized Schedule of US Tariffs on which the United States has placed extra tariffs beyond what was already there in order to depress economic activity in China. Basically to help US industry and punish China for its unfair trade practices, as well as Canada, and Mexico, and the European union, our allies as well.

Steve Ellis:

Yes, the former president was quite tariff happy. There’s no doubt about it. And some of those, President Biden can ease on his own, right? I mean, it’s not an Act of Congress.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, exactly. So a lot of these tariffs, again, there are a certain amount of tariffs, or tariffs and tariff levels are set by Congress, certain ones. The Trump administration tariffs, which have now been inherited and maintained for the most part by the Biden administration, were additional ones on top of those tariffs. And so they used different authorities, Section 301 is one of the big ones, basically making a “national security” argument that these tariffs harm national security. Frankly, it’s bogus. How steal, from our European allies or anything, frankly from our European allies is a national security threat is just not true. And in the China, it’s more complicated. But the point being now is that a tariff automatically makes things from another country more expensive, which means the domestically produced stuff, the stuff that we do make in here in the United States maintains a higher level as well, because they don’t have to compete with a lower cost rival.

Josh Sewell:

And at the same time, China, our European allies and others, didn’t just sit back and say, “Oh well, we’re going to just be suckers for these tariffs.” They have retaliatory tariffs on our products. So, everything that we export, which is more than 6,600 US products or materials, at its peak I believe, are also more expensive, which raises costs for domestic producers. So, costs are going up here. Costs are going up for stuff you import. Again, that just adds again to inflation. And let’s not forget the United States government purchases a lot of stuff. So, everything we’re purchasing domestically or that we’re having to import because you cannot produce it, or we do not produce it here, is more expensive.

Steve Ellis:

Got it. Got it. So these are all inflationary pressures that are driving up, costs that even though they were in place before the recent rise of inflation, they could have an impact on easing inflation by reducing some of those costs. Okay. Shifting gears a little bit here, Josh, but let’s talk about sugar. Budget Watchdog, AF listeners, one thing you should know is that I’m not big on sweets. In fact, the kids of a former colleague of ours were known to declare, Mr. Steve doesn’t like sweets. But I also don’t like subsidies. So Josh, why do Americans pay more for sugar than pretty much everyone else in the world?

Josh Sewell:

Because of the Farm Bill. And I like to point out, you brought up the Farm Bill first, not me. So, basically we have a sugar policy in the United States, which is called a no-cost sugar policy because it’s backers claim that it doesn’t cost the US government any money. And sometimes that’s a technicality that is true, if you only look at the specific provisions in the Farm Bill. But it costs you and me a significant amount of money every year because we essentially pay twice as much as we would in a free market for sugar. So it’s a fairly complicated program, but the main gist of it is, the government says, this is how much we think sugar should cost. It’s 18.7, 5 cents per pound for cane sugar. And I believe it’s 24 point something cents for sugar beets, sugar made from sugar beets.

Josh Sewell:

The government has declared that’s going to be the price of sugar. And so that’s called the price floor. And so now, if the price of sugar goes below that on the wholesale market, we are basically required to take all the sugar that domestic producers make because they used their sugar as a loan, we’ve guaranteed it’s going to get a certain price. So now, lawmaker are like, “Man, we got to do a lot of stuff to make sure sugar prices are more expensive than they would be. So, we do a lot of policies to make sugar expensive.” And the three big ones are, we essentially say American sugar growers can only produce a certain amount of sugar. And so they, the US, they also says, “Okay.” In December, they look at all the numbers and say, “This is how much sugar the United States is going to use next year. And this is the price we’re going to pay for it.”

Josh Sewell:

So, they set a price and they set a target amount of sugar and then they give 85% of it by law. Congress requires 85% of that allotment goes to domestic producers, 15% can be imported. It’s micromanagement. And they micromanaged them even more and say, and one of the ways is they do these things that say, “Okay, every sugar refinery in the United States can produce this amount of sugar. This other one over here can produce this amount of sugar. And then they say, okay, now that 15% that we’re allowing to come in from foreign countries, each country gets a certain amount they’re allowed to export to the United States at which if they exceed that they get slapped with massive tariffs that make it economically infeasible. It’s the nice way of saying it to export sugar beyond a certain amount to the United States.

Steve Ellis:

And this has some just kind of stringing this out. I mean, this has some other real world implications. I mean, some of these countries that are, would be importing sugar are impoverished nations like Haiti, where you’re essentially where, on one hand, maybe doing some foreign aid that wouldn’t even necessarily be necessary if, if we actually imported sugar or reduced these quota systems, we’re propping up industries in Florida and in the upper Midwest. And then also, why did, why does Coca-Cola use high fructose corn syrup? Whereas it uses sugar in Mexico. Well, that’s because sugar costs a lot in the United States. And so we essentially are subsidizing some of this corn production that then is basically more economically feasible because we have this high price of sugar.

Steve Ellis:

All right. Enough sweet talk. So, you’re listening to Budget Watchdog, AF and we’re talking about combating inflation and just a quick tease. This week’s Wastebasket that you can find at taxpayer.net is going to be talking about the SEC Proposed Rule dealing with the climate impacts for investors and for companies and their liabilities. And so, we’re going into our comments on this proposed rule. You should check it out. It’s interesting. All right, Wendy, let’s bring you in. Buy America sounds patriotic, but what is that all about?

Wendy Jordan:

We’ve been working on Buy America issues at TCS for a long time, and it definitely had a resurgence. The idea of buying American had a resurgence during the pandemic, because there was a greater realization during the pandemic of how much we really rely on foreign manufacturing. I mean, people who’ve been paying attention, people who work on policy issues like the three nerds on this podcast, we knew about it. But a lot of people were pretty deaf to the problem of foreign manufacturing of some major products that we rely on the United States. And at TCS, we absolutely, 100% agree it’s important to have American or allied sources of things like protective medical equipment and masks and supercomputers. There are things that we should definitely have a US manufacturer for. And we should rely on US manufacturers for our federal government contracts for those items.

Wendy Jordan:

But Congress takes that Buy American Football, and I looked it up today. The NFL footballs are all made in Ada, Ohio. So, it is literally a Buy American Football and they run with it to a highly protectionist place. For instance, the Berry Amendment, which states back to World War II requires US content, particularly uniforms and clothing, tents, flags, tarpaulins, basically anything made of cloth. But the Berry Amendment also requires not just are you supposed to have, use us cloth and assemble uniforms, military uniforms in the United States, but the buttons and the thread and the zippers and the clasps, all US made. And that has kept an industry in the United States that responds to those government contracts. And that is required by law. A longstanding 80-year statutory requirement for it. But Congress then takes that and twists it. For instance, the United States Navy was looking to replace classic peacoats with a more capable type of outerwear, more weather resistant, more wind resistant. And Congress said, “No, no. No. You’re going to stick with Navy peacoats. And Steve, did you have a peacoat? Does a coast guard issue peacoats?

Steve Ellis:

No, and it’s not peacoats. It’s called a reefer that they have, but the bottom line is it wasn’t very good. And I think the thing to me too on this is that this is something that would serve the sailors better.

Wendy Jordan:

Right.

Steve Ellis:

That that actually would be something that they would wear, that would keep them warmer, better deal with the elements. I mean, we all love Cracker Jacks. Well, I don’t relate so much because I’m not into sweets, but just because that iconic sailor and Cracker Jack had a peacoat doesn’t mean that today’s modern sailor needs that.

Wendy Jordan:

Well, honest to God, Cracker Jack is my favorite candy, so because Miss Wendy is into sweets, but the Navy peacoat is produced in a particular congressional district. And so the Navy peacoat was made under the restrictions of the Berry Amendment. The members really wanted to make sure that the peacoat continued to be made, even though this better, protective outerwear was available, also made under the restrictions of the Berry Amendment. So, it gets twisted, the Buy American requirements and it went in the last five or six years, we saw a flatware. Stainless steel flatware had to be produced for the military, had to be produced at a US manufacturer.

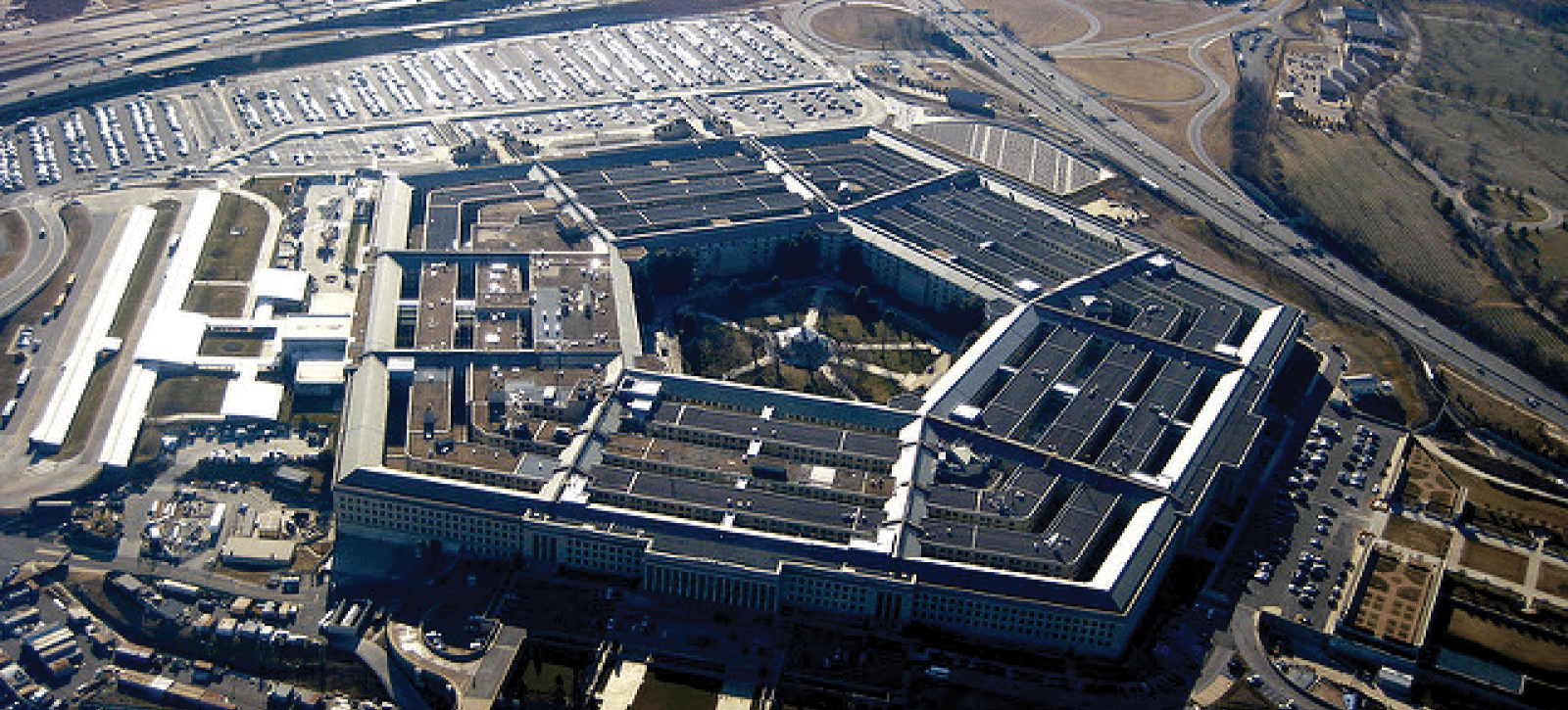

Wendy Jordan:

The tableware, literally the cups, and saucers, and plates had to be produced only in the United States. And we firmly believe at TCS that the best equipment is what the US military deserves. And if the best equipment at the best price is produced by an ally or another country, that’s what the US government, what US government employees in particular, Pentagon employees, deserve. And so we have a problem with this sort of Nth degree of Buy American being forced upon in particular, the Pentagon.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah. I mean it increases the cost for taxpayers. It props up the industries. And so it has these real world issues that also help drive up prices.

Wendy Jordan:

Right. If you restrict the breadth of the suppliers who you can purchase things from, I mean, the economist in me says, “This is a pretty simple supply and demand equation. You’re saying fewer suppliers are eligible. It’s going to drive up your costs, inflation right there.

Steve Ellis:

Exactly. Exactly. So, we’ve talked about production, but what other areas in the supply chain like transportation or more directly shipping. Josh, tell our podcast listeners about cabotage and the Jones Act.

Josh Sewell:

Sure. So cabotage, something I had to look up myself when I first started working on these issues.

Steve Ellis:

I just like saying it.

Josh Sewell:

Essentially, these are laws that have been on the books for a long time that restrict the types of vessels that are engaged in domestic transportation. And so most notably, as you said Steve, maritime, ocean going. And so, another Jones Act, which by the way, was passed in the 1920s, which you may notice as a theme of the laws that we’re talking about here. Sugar program had its beginnings in the 1930s and its modern era basically 1938. Most of the farm bylaws are that way too. Some of the Buy America provisions can go back pretty far, but so the Jones Act, it says that, “Any shipments between US ports must go on. US-owned, US-flagged, US-crewed ships.” So, a US company has to build a ship, own the ship, has to be flagged, basically registered in the United States, and it has to be crewed by an American crew.

Josh Sewell:

Sounds great in some respects. And the justification is being that the idea is you keep a maritime industry, you keep the ability to build ships and you keep the ability to pilot those ships and men in the cruise to manage it in case you need it for later. Both for normal commerce competition, as well as in a time of war, to ship things around the world. Problem is this thing has been on the books for a hundred years and our maritime fleet is small and dwindling year, after year, after year. And so what this means in reality is that you have a smaller and smaller subset of companies that benefit from the restriction that any shipping that comes in the United States, they basically have to unload it all at the port. And those foreign-owned, foreign-crewed vessels didn’t have to, they can load up and leave, but they can’t go to a nearby port, even if there’s a demand at something more efficient.

Josh Sewell:

And so you end up basically increasing costs for producers and for consumers. And then you don’t take advantage of potential efficiencies and reductions in costs from these large efficient shipping companies that could unload at one of the coast reports and go up the coast to another one. And instead we have to have a massive trucking, a massive rail system, which is, has its benefits, but having that competition between rail trucking and coastal shipping, would produce lower cost, lower maintenance cost if you have a less extensive network and biased it towards one particular type. And actually, frankly, would actually reduce traffic deaths. There are studies that show that having this much shipping, instead of doing shipping, you’re putting it on on trucks, essentially increase vehicle miles, increases where and increases the likelihood of accidents. And so it’s a really complicated issue there, but frankly, it basically comes down to a small number of people in the industry, get a lot of benefit from it. And it’s the status quo that just keeps going and going and going, and it goes into all kinds of things besides just container shipping and large bulk shipping.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah. I mean, the thing it’s crazy to me about it is that we obviously have a ship building industry in United States. We build huge warships. We actually also build fishing vessels and crew vessels to go to rigs and such like that. So, that all exists. But even though this law is designed to protect this particular industry, it hasn’t worked. It has failed and it has an impact as you said, Josh, on consumers in the fact that coast wise navigation, you could actually move products from New York to Baltimore, or New York to Florida. And it would be much more efficient to do that bulk on water or containers on water than it is to do it by truck, or to have all these various ships come in and deepen all these ports. And that actually gets to some of the other cabotage laws.

Steve Ellis:

For instance, there’s the Passenger Vessel Act, which is the reason why when you go on vacation in Alaska, you leave from Vancouver, Canada, because they can’t go from two US ports with passengers, unless it is a US-built, US-owned, US-crewed ship. Or you have the Foreign Dredge Act, which precludes foreign dredge companies, the biggest country for dredging, Belgium. From actually coming and dredging our harbor. So, we have much more inefficient system that we pay as taxpayers a heck of a lot more to do. And it also increases costs for consumers. Isn’t that, right?

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, absolutely. And there are two other things that I find crazy about it is that, again, Belgium is not a strategic threat to the United States. They’re an ally. And so the idea that using their expertise would be a threat to the United States is ludicrous. And the other thing is that with the Jones Act specifically in some of these other laws that are protectionism, it’s waived all the time under emergency provisions. When there’s an actual emergency, the administration, this and previous ones, can wave and has wave these provisions in order to get foreign aid to places, in order to basically get products moving faster. And so if we wave these things in emergencies, why even have them? They’re not working. They’re making things more expensive. And when we really need to move stuff, we wave these provisions. It seems like there’s not much reason to have them.

Steve Ellis:

Well, and it has a huge impact on places like Puerto Rico and Hawaii that have to have all of their goods shipped in. And so it’s a big issue. It’s one that flies under the radar, but it could have major consequences for supply chain management, for transportation and for consumer costs. And it’s something that it’s going to take legislation, but it is something that is really worth looking at. So, okay, Wendy, we know that inflation isn’t only affecting the US, but it’s affecting the whole world. But the president can lead the way by reducing some of the impacts on Americans by removing or fixing some of the US policies and laws that contribute to the situation. And that’s what we’ve been talking about. But one thing that has come up in policy considerations in the pandemic and then more recently is the Defense Production Act. So, what is the Defense Production Act and why do we see it as a heavy handed tool that should be used sparingly if at all?

Wendy Jordan:

Well, the Defense Production Act is the younger brother of the legislation we’ve been talking about today. It dates back a mere 70 years to the Korean War. And the statute gives the president the power to compel private industry, to prioritize contracts from the federal government. So, if you’re a contractor who produces only one thing, and it happens to be nuclear-powered submarines, that’s not a problem for you because you only produce nuclear-powered submarines for the federal government. But if you are a contractor who has a robust commercial division, as well as a federal and state government division, then you could have a problem. So, you’re not building nuclear submarines, but let’s say you’re building the easiest thing, the smallest thing to go to is microchips. Let’s go to that. But there are many, many other things that we could use as an example.

Wendy Jordan:

So, if you are producing microchips, you have a commercial business and you have a government business, or some microchip manufacturers have both a commercial and a federal government practice. So the president says, “I am invoking the Defense Production Act on your particular style of microchip.” And that means that every federal government contract that comes in the door at your company for that style of microchip, you have to produce every item the federal government is asking for before you can start to produce against any commercial contracts. So, that’s a problem. If you have a robust commercial side to your business, because you have to tell your commercial customers, “Sorry, the federal government just handed me this order.” And let’s say you’re in the first quarter of your fiscal year, and you have already blocked out what months of production are going to be against government contracts, what months are going to be against commercial contracts. And the government can just hand you a contract and completely throw your plans up in the air.

Wendy Jordan:

Well, that’s an inflationary factor as well, because then tho the commercial customer has been squeezed out of the contract that they had at a reasonable price, they sign the contract, they must think it’s a reasonable price. Now, they’re out of luck with the contractor that has to produce against the federal government’s contract. And so are lots of other people who need microchips. And so, all of those customers are turning to contractors who don’t have what’s called a rated, R-A-T-E-D, a rated contract from the federal government to produce under the Defense Production Act. So, cost go up for everybody else when that’s the case, or they can go up for everybody else when that’s the case.

Wendy Jordan:

So, Defense Production Act has really never invoked for nuclear submarines or fighter jets, but the most recent examples of Defense Production Act invocation for products that have a commercial side to their business as well are COVID-19 tests, COVID-19 vaccines, baby formula, like Josh noted earlier, rare earth minerals, solar panels. Now, not all the formula that is produced and purchased under the Defense Production Act is going to go to federal government consumers. It’s not all going to the commissaries and it’s only going to be purchased by military families or retiree families. It is going to a wider audience, but that’s not usually the case when the Defense Production Act is invoked.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah, and it has its place, but it’s something that seems to be people turn to it really quickly. Like, “Hey, we can get the, we can make these companies make what we want.” Because it’s not just you’re making semiconductors and you’re going to now sell the semiconductors to us. It’s that you’re making widgets and now you’re going to make something else… that the government wants. And so it has that displacement impact

Josh Sewell:

And it can also be very expensive because again, with the baby formula, it’s not just that there’s some priority that you’re producing. It’s actually that the health and human services use Department of Defense aircraft to fly baby formula from Ireland to the United States. And I can tell you right now, it’s a lot more expensive to fly some baby formula than it is to reduce tariffs and allow for bulk export from Europe or Canada even closer, to solve this issue in the long run.

Wendy Jordan:

What about a US-flagged vessel?

Steve Ellis:

All right. We’re hitting all the high notes here. So, way to bring it home, Josh and Wendy. And thank you for having our back. Well, there you have it podcast listeners. We’ve got to battle inflation and policy makers needed better target list and we’ve got one. Let’s hope they’re listening. This is the frequency market on your dial, subscribe and share, and know this, Taxpayers for Common Sense has your back America. We read the bills, monitor the earmarks and highlight those wasteful programs that poorly spend our money and ship long-term risk to taxpayers. We’ll be back with a new episode soon. I hope you’ll meet us right here to learn more.

Get Social