The recent credit rating downgrade of the United States government by Fitch Ratings might have been met with alarm bells and market tremors. It was not. Host Steve Ellis is joined by TCS Senior Policy Analyst, Josh Sewell, and TCS Director of Special Projects, Mike Surrusco, to shed light, context, and analysis of the underlying issues that continue to simmer.

Episode 51: Transcript

Announcer:

Welcome to Budget Watchdog, All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending and tax issues facing the nation. Cut through the partisan rhetoric and talking points for the facts about what’s being talked about, bandied about, and pushed to Washington, brought to you by Taxpayers for Common Sense. And now the host of Budget Watchdog AF, TCS President Steve Ellis.

Steve Ellis:

Welcome to all American taxpayers seeking common sense. You’ve made it to the right place. For over 25 years, TCS, that’s Taxpayers for Common Sense, has served as an independent non-partisan budget watchdog group based in Washington DC. We believe in fiscal policy for America that is based on facts. We believe in transparency and accountability because no matter where you are in the political spectrum, no one wants to see their tax dollars wasted.

And that my friends includes not wanting to see your tax dollars spent paying higher interest rates to service our nation’s publicly financed debt. So today, we’re digging into the recent credit rating downgrade of the United States government from AAA to AA plus by American credit rating agency, Fitch, one of the big three credit rating agencies. The other two being Moody’s and Standard & Poors. Joining me to shed light, context and analysis are my TCS colleagues, Mike Surrusco and Josh Sewell. Thanks for being here, gentlemen.

Josh Sewell:

Very happy to be here.

Mike Surrusco:

Thanks, Steve.

Steve Ellis:

Mike, let’s start with you. In the world of finance, a credit rating downgrade is often met with alarm bells and market tremors because it not only reflects the assessment of an entity’s financial health, but also serves as a stark reminder of the underlying issues that may have brought about the change. So the big question is why did Fitch do it?

Mike Surrusco:

Well, I think the way you characterize it is correct. It’s a reminder of these bigger issues that we at Taxpayers for Common Sense talk about a lot that don’t get enough attention. And I think that’s part of why we find ourselves in this position where Fitch has downgraded the credit rating of the US government. It’s not a huge deal in the markets. It’s not like interest rates are going to spike and the bond markets are going to break open because Fitch downgraded the US credit rating, but the reasons that they give for doing it are eerily similar to what the Congressional Budget Office has been saying for a long time and that we have been saying for a long time.

So again, it’s just a good reminder that these issues are hanging out there, they’re not going away, and in fact they’re getting worse. So I’ll just talk a little bit about the specific things that Fitch points to. So they use the words erosion of governance, which is kind of harsh and probably well-deserved, and they point to these repeated standoffs that we have in Congress. Recently, we did the debt ceiling tango. We’ve got the end of the fiscal year coming up. A lot of stories now are predicting that we’re going to have a shutdown for some period of time, which of course we have poo-pooed, if you will, many times. It’s a waste of money as we have seen in the past.

So that’s the context of what we’re seeing. The numbers are bad too. The debt to GDP ratio is approaching 100%. We’ll break through that here in the next year or two. Probably Fitch is predicting a mild recession in the fourth quarter of this year and the first quarter of next year. I think that’s the economic news that we’ve been getting recently is pretty good. I think inflation, employment, other indicators in the US are pretty good, so maybe hopefully we won’t see any kind of recession coming up.

They also talk about how the Fed has raised interest rates. They’re probably going to do it again to try and keep inflation under control after the pandemic. So you got a lot of challenges obviously with the economy. And then couple that with the political challenges that have been routine over the years, but seems to have sharpened particularly in the last few years.

And then you just have what runs through all of this consistently is that deficits are projected to decline a little bit after the pandemic spending has sort of wanes, but then pick pack up, which of course just adds to the debt. And as we continue to accumulate the debt, that of course has its own set of consequences that we need to address and think about. And finally, just one other thing that Fitch mentions is the Medicare and some of these sort of medium term challenges that, again, these are tough questions that need to be asked and answered. And I think there are overall messages that were not up to it. I think that’s a fair assessment.

Steve Ellis:

That was an in-depth assessment. I appreciate that, Mike. So let’s unpack this a little bit and bring our listeners up to speed on some of the details. One of the things that you mentioned that Fitch was echoing something that the congressional budget office, the scorekeeper, congressional scorekeeper has been saying. So Josh, can you outline a little bit about what CBO has been saying and what was in their most recent long-term budget outlook this summer?

Josh Sewell:

Well, CBO has been saying pretty much the same thing that these credit rating agencies have been saying that we have major fiscal challenges and we have to get up to speed on them. But I think what we should really talk about is that the Fitch agency gave for downgrading the debt is our fiscal health has absolutely deteriorated. I think this is something that we just sort of go over sometimes for those of us who work in this area. But debt has absolutely exploded. I mean, do you by any chance remember what the federal debt was when you started, Steve?

Steve Ellis:

It was just over $5 trillion in 1999. And we actually were running a surplus that year.

Josh Sewell:

Right. And now it’s 32 and a half trillion dollars as of the end of last fiscal year.

Steve Ellis:

It would’ve been worse if we had not been on the game. Just saying that, Josh.

Josh Sewell:

Well, exactly. I think the point is that Congress and presidents have not been making tough decisions. The reality is, we go through a couple more numbers, is that it’s one thing to have deficits that a pile on debt, but the debt that’s a percentage of the output of our economy has also been growing. And that’s where the real concern is even for folks who say, “Oh, deficits don’t matter.” Look at the economy is growing faster and the GDP growth is accelerating the debt. That’s not happening. So the debt to GDP ratio was 97%. That means our debt equaled 97% of our economic output at the end of last fiscal year.

Steve Ellis:

And a key point on that is that’s the public debt. So it’s not the total debt because there’s money that we’ve… As much as we talk about social security and Medicare as being challenges, those are particularly in social security’s case future challenges. We’ve been running surpluses into the Social Security Trust Fund and the Medicare Trust Fund. Not so much Medicare recently that we’ve been borrowing that money. And so we actually, the treasury owes social security with interest that money that’s been borrowed. So actually the total debt, not just what we owe people outside of government is even higher than 100%.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah. And I think that’s important to state. And so the big point of this is that debt has been growing for a long time, and frankly, the debt to GDP ratio has been growing since 1981. That’s 40 plus years that debt has actually been outgrowing our economy in fits and starts. Obviously some years are a little better than others, and it’s going to accelerate in the future. I think that’s an important point.

Steve Ellis:

So the second factor as we’re walking through this with Fitch is this erosion of governance. And I know Mike touched on this a bit, but I think that, let’s put a little finer point on it, but Josh, Mike, what would you see is some of the erosion of governance? And then I guess the other thing is why Fitch now?

Mike Surrusco:

Well, I’ll go first just because I want to make one point also about debt to GDP. When your debt is equal to your GDP, which is about where we are, that’s well above the median ratio for other economies that Fitch rates that are AAA. So that may also answer your question, why now? I mean, it’s a pretty symbolic milestone when the debt exceeds your economic output. And so that may be why they decided to finally do that now. I think just watching the tone and tenor of our political discussion and using default as this tool is a little scary.

I think over time that’s become a normalized thing where we’re going to use a potential default as a bargaining chip. We’re going to shut down the government and really not care whatever the political consequences of that might be. I mean, it seemed like a big deal back when Gingrich did it, but now it’s just sort of thrown around almost certainty. So maybe that also answers why now? Just the combination of all of these things, the amount of debt, the political situation, the economic situation, they all come together now and it doesn’t paint a very pretty picture.

Steve Ellis:

So how would you paint the picture, Josh?

Josh Sewell:

Well, I mean it is pretty bleak. Again, I don’t know about causation, risk correlation, but 1996 you started more or less at TCS. That was the first time we had a massive government shutdown for a long time. And so that was three weeks as Mike mentioned. I remember that when I was definitely not working at TCS and it was a big deal. We had a 13-day shutdown down when my son was born in 2013, and that seemed like a big deal. And now then we had 200 President Trump.

Now, the minute the debt limit deal was signed, basically there were folks in Congress who said, “We’re going to have a shutdown this fall.” And I think there’s a 97.9% chance we’re going to have a shutdown this fall because a month and a half isn’t enough time to do work work. And I think it is this idea, do you think this Congress will solve problems quickly? No. And so I think that’s where that erosion of governance comes is I don’t know anyone who has confidence that this Congress and the previous Congress, and honestly probably the next Congress, no matter what happens in the election, is going to be able to sit down and do the business of Congress, which is pass the bills that need to fund the government, make those decisions. So where is the trust?

Steve Ellis:

Budget Watchdog AF listeners, let the record show that I was still in the Coast Guard in 1996, but the point is well taken. I definitely remember the shutdown and being essential and going into work. That was a term that they used then. But anyway, I think that certainly that last point that you made about how the ink wasn’t even dry on the president’s signature on the so-called Fiscal Responsibility Act, which was the debt ceiling deal that when lawmakers were starting to say that they were going to walk away from that and they wanted to… That was a ceiling, not a floor as far as funding, which I think is what everybody understood at that point and realizing that that’s going to be dysfunction junction here at the end of the fiscal year.

And we said this at the time, we got to thank our lucky stars that actually they suspended the debt limit until 2025, which gets you through the next election so that hopefully whomever is in office and in Congress is going to be able to lead and get a more solid positioning. And that brinkmanship that Mike is talking about is the reason why as our podcast listeners know, at TCS, we’d long supported the idea of having a debt limit because it would concentrate the mind and bring attention to this increased debt. But that limited use as a tool just to get attention is now become… It’s too risky. And we call it for scrapping it for the first time.

Not all our Budget Watchdog allies are in the same position, but would we like to have a better mechanism, a better deal, a better process? Yes. But it’s just too risky because unlike a shutdown, which you can kind of… It’s wasteful, it’s damaging to the public psyche about government, but you can recover from that debt basically not reneging on our debt, not paying off what we owe and risking the full faith and credit of the United States Treasury is a huge, huge risk. And so I can see Fitch… And there are questions about governance and so that certainly hits that.

So we’ve talked about the rising deficits and increasing debt, and then they also had these medium term challenges talking about Medicare, which we mentioned, and even social security. And so what are the ways forward? Do you see either of you any way forward on those major entitlement programs during the next presidency?

Mike Surrusco:

Well, I think that the problem is, again, all of these things are related. And so just as we’re now talking about what I characterize as near misses when it comes to things like the debt limit and defaulting, we are not in a position to begin to try and tackle these much more difficult, complicated, politically fraught questions. Even if you go back a decade or so when the Simpson-Bowles commission was doing its thing, and we did the sequestration and the Budget Control Act. The outcome of that wasn’t great, but at least we were having conversations about structural problems and putting some political capital on the table.

We’re not there. I didn’t watch the presidential debate the other night, but I don’t imagine that there was a ton of oxygen consumed talking about their plans to bring down the debt, bring down deficits. Remember Donald Trump famously said he was going to pay off the debt in 10 years or something. And then of course that went in the opposite direction.

Steve Ellis:

They did mention in there that… I think it was former Governor Haley, former Ambassador Haley mentioned that they added 8 trillion… Which is a little bit more in $7.2 trillion to the debt during his term in office.

Mike Surrusco:

Yeah. So I mean that that’s sort of a non-answer to what’s the path forward for Medicare or an aging population and the challenges that’s going to bring. I don’t even know where we even… We’re not even on the starting line, I feel like with that.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah. I mean, I’m an optimist in some of these areas only because I think we have to. It’s something we have to take care of. And so where there is a will, there is a way. And you’re right, there isn’t a will right now, and that’s the real challenge. But I think these structural issues are becoming more real. They’re starting to become actual challenges to people’s livelihood soon. The Social Security Trust Funds, if you put those two together basically by 2033, the amount of money coming in is only going to cover 75% of the benefits being paid.

So the surpluses are gone. And so that’s not very far away. And so if you get to there, you’re going to have to backfill it by increasing taxes or massively increasing deficits or you’re going to have to cut benefits. And part of the Medicare stuff, it already is. We already are spending more than we’re taking in. I think it’s the hospital portion of it is already leading money, so to speak. And so when this starts to actually affect people’s ability to take these benefits, it’s going to matter. And social security, Medicare, that’s what 40%, almost 50% of our budget for those together. It’s a ton of money. It’s a ton of benefits. It’s a big issue for people and voters.

Steve Ellis:

So 2033, you mean when I’m turning 64 and about to cash in? That’s what you’re telling me, Josh?. All right.

Josh Sewell:

Yes. It becomes very real for many people. And I share displeasure, we’ll say with Congress and the previous president. I’ll dislike the next president. That’s what you do when you’re a Budget Watchdog. You always get disappointed. But I do think we’ve had meetings. I’ve had numerous meetings with Freedom Caucus folks. I’ve had meetings with Progressive Caucus folks on the Farm Bill and other issues. At the end of the day, I’m not a kumbaya person, but people do want to solve problems. It’s finding the right people to take political courage and actually start to make decisions in areas that they like, not that they oppose, in areas that are important to their voters and their constituents, not just their opponents. And I think that’s political courage.

The TikTok era ain’t a time for political courage it seems like, but I think there are real lawmakers out there on both sides of the aisle. We just have to keep working. And when the environment makes it possible or requires it, I think people will stand up. That’s what makes me an optimist.

Steve Ellis:

You’re listening to Budget Watchdog All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget spending and tax issues facing the nation. I’m your host, TCS President Steve Ellis, and we continue now with Mike Surrusco and Josh Sewell. We’ve touched on this a little bit. Mike mentioned Simpson Bowles, that fiscal commission. Obviously the whole budget control Act. And that actually reminds me is that Fitch isn’t the first credit rating agency to downgrade the US debt. One of you two want to fill me in on what happened back then?

Mike Surrusco:

Well, the more things change, the more they stay the same. That was 2011, and I don’t have that decision in front of me, but I am probably on safe ground saying that many of the things that were cited in that decision were the same as this one. I feel like there’s this idea of American exceptionalism that has spread into a fantasy about what we can and can’t do as a country, certainly in the economic space and probably in lots of other areas too that are for another podcast.

I think maybe this speaks to Josh’s point. At some point we’re going to be brought back to Earth and that hopefully isn’t too messy. It’s at that point, I think that what happened, what Josh just described happens is that people begin to see these kinds of issues as more important than whether or not the military can host a drag brunch or some of these other culture war issues that honestly, I think are distraction more than anything else and have really come to consume far too much of the political discourse.

Steve Ellis:

So Standard & Poors, S&P Global, when they did that rating, moved it from AAA down to AA plus back, like you said, more than 10 years ago. It’s still AA plus. They haven’t upgraded it. It’s stayed there. And so now Moody’s is the only outlier. But I guess the question too is what impact does it have? What’s going to trigger this? And I think that Josh’s point about social security not being able to pay full benefits is really going to grab attention. As much as you feel like a commission is a dodge and Simpson-Bowles didn’t have anything come out of it or whatever, but it seems that you need to have some sort of space to create this sort of recommendation.

So famously in the mid-80s, Alan Greenspan was the last time social security got saved as they made recommendations then. I think that it seems like that’s what’s going to have to happen is to have something like this because you saw the State of the Union where basically President Biden got everybody to agree to take Social Security… Reforming of Social Security, Medicare off the table. I think that something like that is what’s going to be necessary.As much as I’m not a commission fan. Josh?

Josh Sewell:

I agree. We’ve criticized commissions in the past, but at this point I think there would be a benefit to having folks not have all of us be on the camera immediately, not have every member of Congress who’s running for reelection the day after they’re sworn in to have to make these decisions out in the public. We can have some of this dialogue and debate and then eventually it’s all going to have to be voted on. But it also has to start with the acknowledgement that these are issues that we are going to pay for our commitments in these programs. And then every option has to be on the table.

You can’t save these programs just with revenue and you can’t save these programs by cutting other programs. You’re going to have to cut spending in certain areas. We’re going to have to raise taxes. We’re going to have to raise revenue in other ways. We’re going to have to start making tough decisions because 40 years or more of not making decisions of being able to have all the defense spending we want and cut taxes and increase entitlements and create brand new entitlement programs. And that’s not entitlement disparaging, that’s just the fact that we are providing these social benefits to folks in healthcare and retirement and other areas.

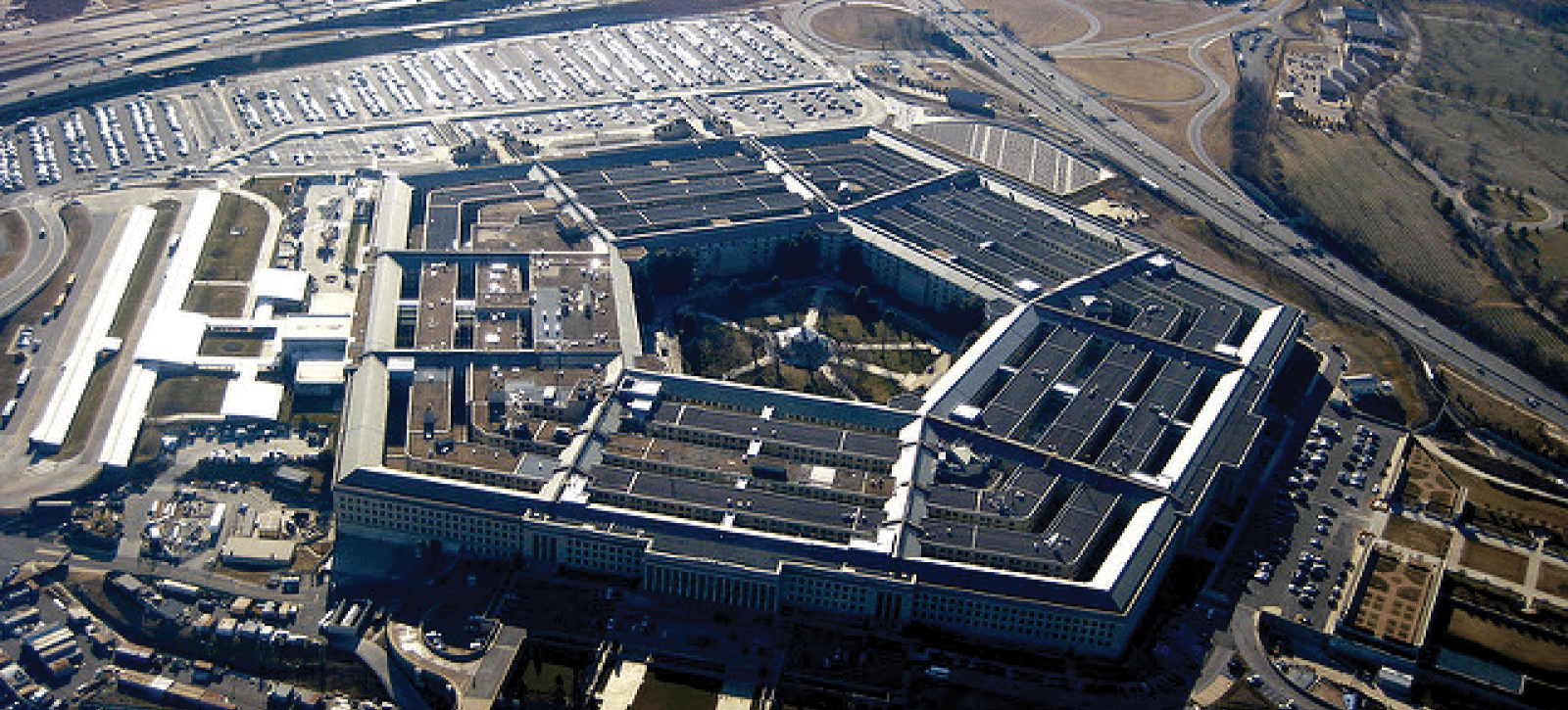

We just have to start paying the bills because in the end, if we don’t, we’re going to be paying so much money on just our past spending decisions through our debt service that it’s going to become one of the largest part of our budgets and will, according to CBO, exceed the entirety of our discretionary, or Pentagon spending in the not too distant future. And that makes absolutely no sense. It’s okay to take on debt to pay for some things, but you can’t run everything on your credit card.

Mike Surrusco:

I’ll jump in if I can real quick on… One of the things that we have sound of the alarm a lot at TCS are these sort of bogus budgetary sleight of hand that Congress likes to do. We’re going to push the costs out beyond the 10-year window. Things are going to expire at some later date so that they don’t actually get included in the so-called score or the cost of legislation. And that’s the kind of stuff that you can’t do that forever because as Josh says, sooner or later the bill is going to come due.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah. Josh is mentioning about interest. We’re already spending hundreds of billions of dollars every year servicing the interest and by the end of the decade, looking at spending more on net interest than we actually spend on the Pentagon, which would be basically approaching a trillion dollars. And that’s the interest rates on what was already bonds that have already been issued treasury T-bills that had already been issued. But up until the pandemic, you had low interest rates and that allowed borrowing without undue strain on the budget. But now we were seeing much higher interest rates that they’re going to have to meet when they’re issuing these treasuries, and that’s going to have far reaching consequences for housing, private investment, overall economic stability. How should we appreciate the potential impact of further interest rates hikes on economic growth and further strain on the ability of the federal government to manage the debt obligations?

Josh Sewell:

It’s going to make it a lot harder. I mean, you have to pay more to borrow. It’s going to make it tougher for us to have the flexibility to actually respond to disasters, to respond quickly, or to increase the investments in areas that we think would serve the public good in some of those entitlements. I bought a house a year and a half ago. I pay a different interest rate than I did 10 years ago, and it’s not nearly as high as it is now. So I can only imagine how hard it would be to finance the house I bought now, if I had to. This year, I wouldn’t want to. I don’t know if I would. I don’t think I could afford it. And I think that’s the kind of issue we’re going to see when there are other things that we spend from our government. It doesn’t have to be that way. We just have to start making decisions, have some political courage and understand math.

Mike Surrusco:

Yeah. I’ll just add that to your point about the historic low interest rates. I mean, looking back over the last 10 or 20 years, we’ve had very low near zero interest rates for so long, and now you’re seeing changes in the way that entire sectors are doing business because they no longer have access to free money. And so back to your question at the top, why now? Well, and this is one of the things that Fitch pointed to is that not only are rates higher than they have been in a long time, they’re going to continue to go up, and it’s difficult to even forecast what that change alone compared to where we’ve been over the last 20 years is going to do just to the decision-making that people do and an unmanageable debt burden is just going to intensify that.

Steve Ellis:

Fed chair, Jerome Powell is out in Jackson Hole right now, and they meet and we’re going to hear more about what they plan in the future and whether we’re going to see more interest rate increases or how they’re going to deal with tackle inflation. But thank you gentlemen for joining me here to help explain Fitch and some of the dire consequences. Policy makers seem to be whistling past the fiscal graveyard, but we need to get this under control and we need to move forward. So thanks again for joining me, Mike and Josh.

Mike Surrusco:

Thanks, Steve.

Josh Sewell:

Always uplifting.

Steve Ellis:

Absolutely. Well, there you have it podcast listeners. The growing federal debt in the United States poses serious risks to the economy. This is the frequency. Mark it on your dial. Subscribe and share and know this, Taxpayers for Common Sense has your back, America. We read the bills, monitor the earmarks, and highlight those wasteful programs that poorly spend our money and shift long-term risk to taxpayers. We’ll be back with a new episode soon. I hope you’ll meet us right here to learn more.

Get Social