The new outlook from the Congressional Budget Office is being read as good news. Growth continues. Inflation drifts down. Unemployment stays low. Taken at face value, it looks like an economy that has steadied itself. A closer read tells a different story.

In a healthier economy, you would expect stronger growth to come from rising productivity and labor force expansion. Inflation would be clearly moving back to target, allowing the Federal Reserve to cut rates because it could. In a healthier fiscal environment, interest costs would ease as confidence in the long-term outlook improved, meaning fewer taxpayer dollars would be needed just to pay interest on federal debt.

None of that is what CBO is describing.

Start with growth. CBO projects faster growth in 2026. Except, the increase comes largely from a short-term boost tied to the 2025 reconciliation law, which pulls tax changes, incentives, and spending forward, and from federal spending delayed by last year's shutdown that is pushed into early 2026. In both cases, demand is shifted into the present rather than sustained over time, lifting growth temporarily and leaving future years with less momentum because that activity has already occurred. Once those effects fade, growth drops back below 2 percent.

The labor market points in the same direction. Employment rises in 2026 and then slows. Unemployment barely moves. In a stronger economy, that stability would reflect robust labor supply meeting demand. In CBO's forecast, it reflects constraints on both sides. Labor demand softens after a brief boost, while labor force growth remains weak, largely because net immigration is lower. Stability here isn't a sign of strength. It's a sign of limited capacity.

Inflation makes the constraint even clearer. In a cleaner recovery, you would expect inflation to fall back to the Federal Reserve's target and stay there. Instead, CBO projects inflation remaining above target for several years, pushed up by tariffs and near-term demand. At the same time, the Fed is expected to cut short-term interest rates in response to labor-market weakness. That combination matters. Policymakers are easing monetary policy not because inflation has been beaten, but because the economy can't tolerate tighter conditions. They're choosing between imperfect options, not responding to a problem that's been solved.

Interest rates. Short-term rates fall as the Fed responds to near-term risk. Long-term rates rise as investors demand greater compensation to hold federal debt over time. In a more resilient fiscal and economic environment, those rates would tend to move together. Their divergence suggests markets remain uneasy about the long run, even as the Federal Reserve steps in to manage the near term.

What's most striking is how little all of this changes the broader outlook. Despite new legislation projected to add roughly $3.4 trillion to deficits over the next decade—and trillions more once additional interest costs are included—along with tariff changes, revised immigration assumptions, and expected productivity gains from artificial intelligence, CBO says the trajectory through 2028 looks much like it did last fall. The takeaway is that these policy changes are simply shifting the timing of growth and inflation, not improving the fundamentals.

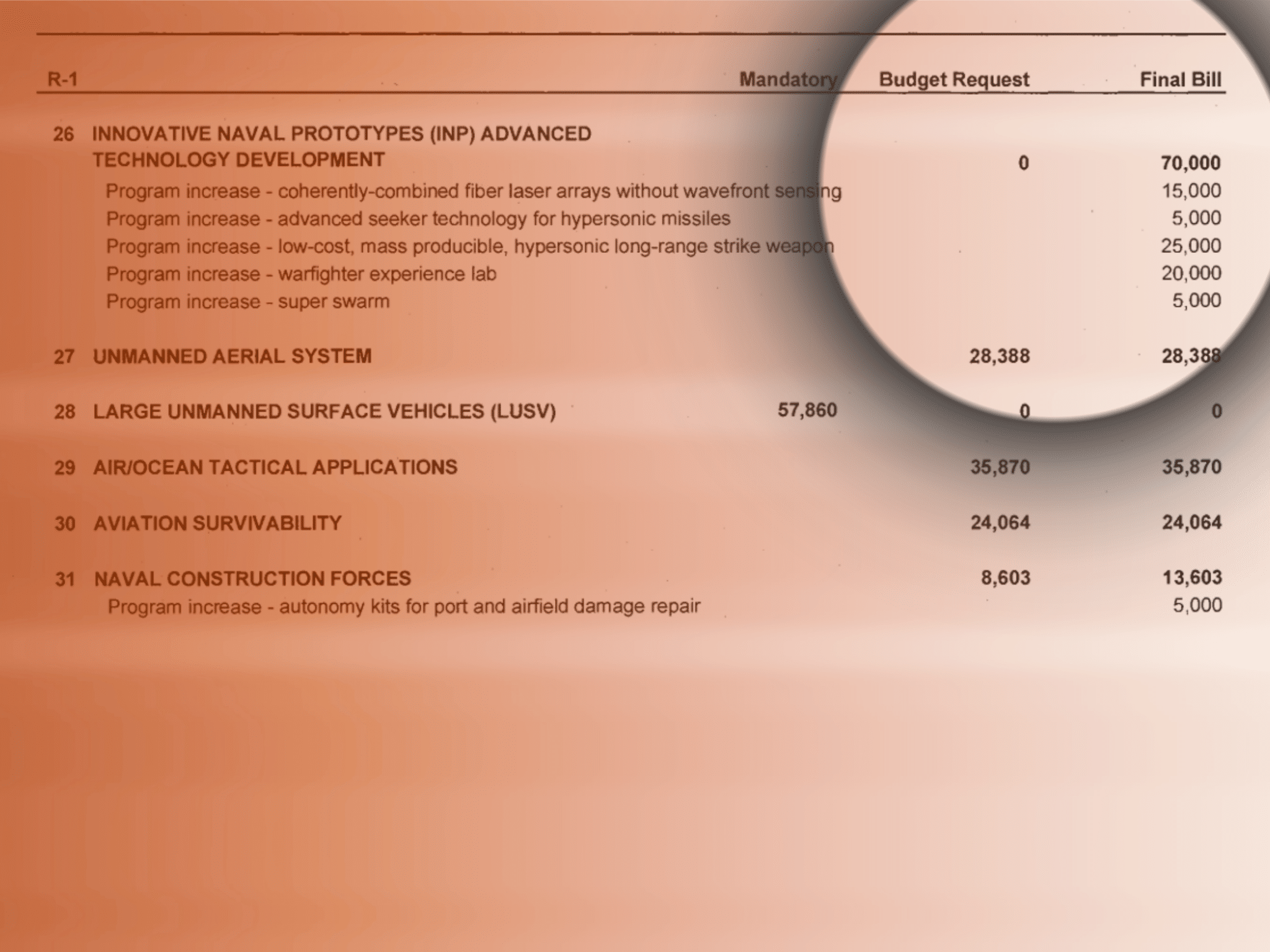

So, the economy is holding together, but it isn't being put on a stronger footing. At the same time, higher long-term interest rates and soaring debt mean more federal dollars will be devoted to servicing past borrowing, leaving fewer resources for priorities like infrastructure, defense, and disaster response, and increasing the economy's vulnerability. That's the real story CBO's numbers quietly tell.