Volume XVIII No. 33

You know that saying you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink? Seemingly the same principle applies to elephants and donkeys confronted with the need to make tough choices in managing spending on our nation’s water resources.

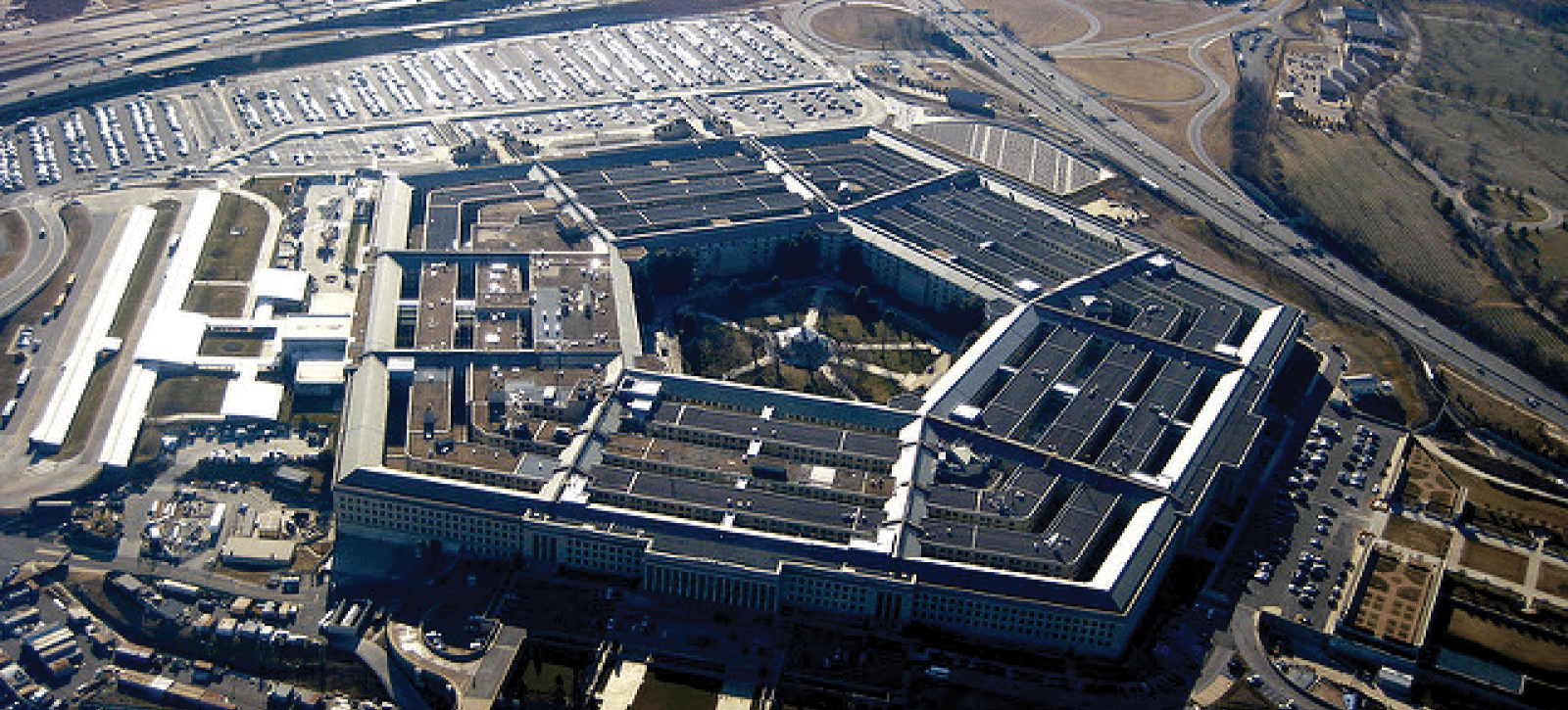

One of the main pieces of legislation directing water infrastructure policy and authorizing new water projects for construction across the country is the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA). In the past the bill was busting at the seams with hundreds of projects that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers could construct. But coming to agreement on a new version, the last one was passed in 2007, has Congress in a bind.

WRDA’s of old were pretty much nothing but earmarks. Hundreds of project authorizations, each with a specific location, spending amount and done at the behest of a member of Congress, made these projects, by Congress’ own definition, earmarks. Now under an earmark moratorium, Congress has to rethink how they write a WRDA.

One problem is that Congress used to treat WRDA’s like a kid in a candy store. An authorization is just a license to hunt for appropriations (actual spending). Because an authorization didn’t really cost lawmakers, but could produce great press, Congress pumped them out like monopoly money. For many projects the high point of their existence was being touted in some lawmaker’s press release. Not even a shovelful of dirt would be turned to move the project along. So over the years, the backlog of projects that were authorized but not yet constructed ballooned to more than $60 billion. To put that in perspective, the Corps usually receives less than $2 billion in construction funding annually.

This purportedly fat free gravy train has dried up. How can policymakers move forward on projects without naming each one individually? The Senate’s solution was to tell the Executive branch that whatever projects they thought were hunky-dory were fine by them. An irresponsible abdication of power. The House is reportedly (they supposedly have a bill drafted, but aren’t sharing it with the public yet) creating a system where the local interests drive the process, coming to the Corps for a project that then gets a thumbs up or thumbs down from Congress. A common congenital defect of lawmakers seems to be that their thumbs are stuck in the up position, so absent other reforms we will likely see the backlog continue to grow under either of these schemes.

It doesn’t have to be this hard. Instead of working around the earmark moratorium, lawmakers should use this opportunity to create a prioritization system that will only green light the most economically justified and most important projects. Under current rules any project where the projected benefits exceeded the project costs by even a penny can be advanced. Considering we still have a $650 billion deficit and some looming financial obligations, this makes no sense. In addition, they should tie the total amount of authorizations to likely future amount of appropriations so the backlog doesn’t grow. Furthermore, a prioritization system with regular oversight will demand better projects and analysis from the Executive branch. And the metrics and criteria in the systems can always be adjusted if need be.

That still leaves the $60 billion plus backlog that already exists. Lawmakers need to design a project blind system to take a machete to that thicket. The Senate proposed a commission to recommend projects for deauthorization but so severely limited its scope and discretion that it is hard to see it accomplishing anything. The House needs to do much better and err on the side of eliminating more projects, not less. If a project is worthy, it can be re-authorized.

Lawmakers hate to tell constituents and special interests “no.” One way they can help themselves is to set up a system where they can say “I’d like to, but I can’t.” That’s what a prioritization system can do for lawmakers: free them from making politically difficult decisions. By swallowing hard and making smart and common sense policy decisions to limit and prioritize what the Administration can propose and what Congress can approve and fund, we can have a WRDA bill that taxpayers can stomach.

Get Social