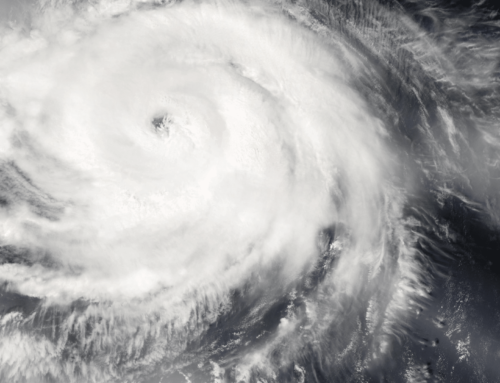

It’s August 29th, 2022, the 17th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina making landfall on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi and Louisiana. 17 years since the country watched as much of a major U.S. city plunged underwater and more than 1800 lives were lost. On this heavy-hearted anniversary, Steve Ellis is joined by TCS Senior Policy Analyst Josh Sewell to define the role the federal government plays in ensuring communities have their own plans in place that are tailored to the risks and opportunities every disaster presents.

Listen here on Apple Podcasts

Episode 28 – Transcript

Announcer:

Welcome to Budget Watchdog All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending, and tax issues facing the nation. Cut through the partisan rhetoric and talking points for the facts about what’s being talked about, bandied about, and pushed in Washington. Brought to you by Taxpayers For Common Sense. And now the host of Budget Watchdog AF, TCS President Steve Ellis.

Steve Ellis:

Welcome to all American taxpayers seeking common sense. You’ve made it to the right place. For over 25 years, TCS that’s Taxpayers for Common Sense, has served as an independent nonpartisan budget watched on group based in Washington, D.C. We believe in fiscal policy for America that is based on facts. We believe in transparency and accountability because no matter where you are on the political spectrum, no one wants to see their tax dollars wasted. It’s August 29th, 2022, and today is the 17th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina making landfall on the Gulf coast of Mississippi and Louisiana, 17 years since the country to the day watched as much of a major American city plunged underwater and more than 1800 lives were lost, and just last week was the 30th anniversary of Hurricane Andrew, which is still the strongest and most impactful hurricane ever to hit South Florida.

Steve Ellis:

On this heavyhearted anniversary, we’re joined by our good friend and TCS senior policy analyst, Josh Sewell to help us understand the role the federal government needs to play to ensure communities have plans in place that are tailored to the risks and opportunities, the disaster presents because every disaster, while it may be a tragic opportunity and opportunity, nonetheless, to remake these communities, to make them less vulnerable, to inevitable future disasters. Josh, you always get the easy topics.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, this one ain’t easy, but it’s really, really important.

Steve Ellis:

Ain’t that the truth? Josh, even if 2022 turns out to be a relatively light year for hurricanes, we know there will be storms in the future, and if your house or community is hit by a major hurricane, it doesn’t matter to you if it was the only storm that year or one of several dozen. On this 17th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, is America better prepared for these inevitable disasters?

Josh Sewell:

As a whole, no. First, we keep seeing disasters that surprise us. Some communities are safer now, but many are not, and that still needs to change.

Steve Ellis:

Josh, I teased this a little bit. Tell our Budget Watchdog AF listeners about this 2022 season and what’s going on here this year as far as hurricanes.

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, so certainly this has been a very quiet hurricane season. We are here in late August and there have only been three named storms and all of them have been tropical, which means they’re not as severe as a hurricane, so it’s been very quiet. However, that does not mean it’s going to stay quiet. As we mentioned in the intro, Hurricane Andrew was the first, as an “A,” was the first name storm of that season, and it became to that time, the most destructive hurricane, at least to that point, in history for the United States, and so this late in the year also Katrina was this late in the year, and that obviously had a very costly effect on people, both in property, and extremely importantly, in lives, so just because it’s been quiet so far doesn’t mean it’s going to stay that way.

Steve Ellis:

Got it. Yeah, and I mean, Andrew was only one of, I think it’s four Cat 5 hurricanes that hit made landfall in the US since 1900. Then Katrina wasn’t by far the last storm in 2005. You had major storms, Rita and Wilma, and then you went five letters into the Greek alphabet, they actually ran out of names, and they last named storm, Zeta, was in, I think, December 30th, so yeah, clearly, we’re not out of the woods, I’ll put it that way. We’re adding into the more active months. You said that this needs to change, so what are some of the concrete steps? What are some of the things that communities need to do? What does the federal government need to do to entice states and communities to take these roles?

Josh Sewell:

First off, I think we need to start preparing for the someday inevitable. We know the disasters are going to happen. You may not know exactly when, but disasters will happen and particular disasters will happen for communities depending on what they face. Before we get into it too much, I think it’s important to talk about the fact that disasters are where government can Excel or fail, so the stakes are extremely high. When we do disaster preparation and disaster response well, it saves money, but even more importantly, it saves lives. If we do it wrong, people lose property, they undergo all kinds of stress. If you’ve ever been involved in a flood, who’ve been involved in any sort of disaster, it is extremely stressful, and again, bad policy can lead to people dying, so this is an extremely important thing to work on.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah, I mean, the first step is really acknowledging the risks that these communities face, and yet we have programs like the National Flood Insurance Program that has baked in cross-subsidies that hide the risk and actually don’t communicate that to the people through the premiums. Even if you had subsidies outside the rate structure, you would actually be able to understand that you’re at a higher risk than another house and do things to mitigate that risk at a property level and then also communities could target those areas to do this and so I think that this is just really critical. Risk communication is one critical step where the government is falling down through its own program that was created in 1968, the National Flood Insurance Program.

Josh Sewell:

One of the things about the National Flood Insurance Program, that’s always boggled my mind is when folks like Taxpayers for Common Sense and the coalitions we work in try to make the program better. We give a significant resistance from folks who are representing individuals and communities that are at the most risk. I say that, and as you mentioned, there’s so many subsidies within flood insurance that ends up hiding the amount of risk you face, and so now that actually the program is moving towards what I call “true risk,” so the rates are moving towards being based on actual risks, basically people are having to cover the cost of reality, but elected members of Congress have been very resistant to the massive, at times, let’s be honest, it has been massive increases in rates that people are going to pay, but the people who are potentially paying the most are seeing the greatest increase in rates are the people who are at the greatest risk of loss.

Josh Sewell:

Again, it’s not just that you have at risk of loss of property. When you’re in a flood zone or you face a flood, even if you’re not technically in a flood zone, because let’s be clear, sometimes the maps aren’t always accurate because of things have changed, conditions have changed on the ground, conditions have changed in the climate, so places that used to not flood are at risk of flood now.

Josh Sewell:

If you are at risk, you’re at risk of losing your life, and I think that’s extremely important when we look at some of the floods that have happened recently, so you see places that you have significant more risk than you used to, or perhaps that people just didn’t realize that they were in risk. I just think of the floods that were in Tennessee recently, and now actually, this year in the Eastern Appalachians of Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, so again, I mean, I say this over and over again, we really are concerned about disaster policy, because it costs us money and it causes disruptions, but this is one of those areas where getting it right, really will actually save lives. I love saving dollars, but I mean, if you can actually save lives, it becomes a moral issue.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah. Well, and I think Josh that before I got into this business, if you would, I was an officer in the Coast Guard whose job literally was to save lives, so I certainly get that and about communicating the risk. The flood insurance program is a classic case of concentrated benefits. There’s people in more than 60% of the policies are in Florida, Texas, and Louisiana, and so those members really support it, but it is this kind of twisted sort of thing whereby trying to keep rates low, they’re actually keeping their constituents at risk, those that they’re supposedly serving, and so it’s really bizarre, and then the rest of the country is actually paying for those huge subsidies, and the fact that the program is borrowed tens of billions, 30, 40 billion from taxpayers.

Steve Ellis:

You’re listening to Budget Watchdog All Federal, the podcast dedicated to making sense of the budget, spending and tax issues facing the nation. I’m your host, TCS President Steve Ellis, and we continue now with TCS senior policy analyst, Josh Sewell. We’ve talked, Josh, a bit about some of the programs that are in place and planning, but we know that from experience that after a disaster is really when the wallet opens, Uncle Sam’s wallet opens, and the money flows. Since 2017, federal taxpayers have shelled out more than 139 billion in disaster assistance for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria, Michael, and Florence, as well as the wildfires in the Western United States and other disasters. But we’ve made some changes into these funding formulas of this post-disaster funding where it can actually help to prespond, right, Josh? Can you talk to our listeners about that a little bit?

Josh Sewell:

It’s very important to have proper disaster response, but the best time to respond to a disaster is before it happens, and that means you’re basically preparing to do the response and if we do it right, oftentimes you can prepare a community in such a way that what would’ve been a disaster is either not a disaster, or has much less damage. That’s what we call “pre-disaster response.”

Josh Sewell:

Starting about 10 years ago, really, under the Obama administration, there was a big move towards, it’s called “mitigation,” we call it “mitigating future disasters,” and so within some of these response programs, part of the money is set aside. We’re obviously going to have to spend money immediately after disaster to help people. First of all, you’re rescuing people, you’re doing emergency repairs, you’re giving them the food, the water, the shelter. These are dollars that have to go out quickly for actual response. But when you’re doing that response, instead of, for example, fixing a levy that has failed, or simply fixing a bridge that failed to the exact standards it was, we need to turn some of that money to make people stronger, to make communities stronger, to make them safer, so that’s an important thing. Some of the money is moving that way.

Josh Sewell:

But also, even before a disaster strikes, when communities are sitting here, you’re doing your budgets for the year, or for your five-year plans, whatever you’re doing, that’s the real time to think about, how do we respond? How are we going to respond to a flood? Because it’s going to happen someday. That’s the truth about floods, tornadoes, some disaster is going to happen at some point, and communities can identify the risks and start preparing for that. I think it’s important, though, is to talk about how we spend so much more money on response than we do on preparation. Now, that is changing a little bit, but not enough.

Josh Sewell:

As an example, for last year, for 20 fiscal year 2021, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA made 1.16 billion available under this thing called the “Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities/BRIC program,” and also some of that went to a technical part called the “Flood Mitigation Assistance.” This good program about, it’s exactly what it says, building resilient infrastructure for a community or mitigating floods before mitigating floods, before they happen, spectacular program. $1.16 billion. But that funding was out of a pool of 788 applications for $4 billion in BRIC and another half a billion dollars in Flood Mitigation Assistance, so the demand is much higher than the amount of funding going out the door, so that’s something that we really need to think about is how to increase funding, get the funding out the door better for these disasters because tackling a disaster before it happens is actually one of the greatest ways to save money.

Steve Ellis:

Josh, we know one of the challenges here is the money that is appropriated, now some of it is being siphoned off of post-disaster funding, I get that, but then the money that’s in the budget, that’s in the regular appropriations, that’s all competing with everything else in the budget, whereas after disaster, these are all emergency spending, and so we don’t care about what the budget is, we’re just going to spend however much we want to spend. That’s one of these challenges in competitions, right? But I guess one thing else I take out of what you’re saying is at least it seems the communities are getting it, that they’re saying, “Hey, there’s money out here,” and of course, they want the money, but by the same token, if they have good plans in place, they’re trying to do things to do the right things to be prepared for future disasters.

Josh Sewell:

Exactly. There are communities that are moving that way. Now, as you said, we tend to open up our wallets after a disaster. That is often good. It’s often what you need to do. Now, the problem is we aren’t as diligent about ensuring that that money is going to where it’s actually needed, and let’s be clear, in the heat of the moment we may appropriate, make available more money than is actually needed, and so that’s a really important part of, again, about identifying risks, identifying potential costs, and getting that budgeted and planned for upfront, but also, in that competition, we have a very shortsighted understanding of what costs are.

Josh Sewell:

If you’ve listened to this podcast before, we talk all the time about conventional budget office scores and claim savings that may happen later. In truth, when communities prepare for disasters, when they, let’s say if you’re in a flood-prone area, if you build your infrastructure better, so basically, you’re literally making buildings higher, you are implementing sort of this green or gray infrastructure where you use the natural courses, the rivers, instead of fighting against them. You do a little bit of this, you keep your wetlands in the low areas, and you build only on the higher areas, you actually end up saving money, and so this becomes a budgetary issue where we need to do a better job of rewarding communities on the federal level of changing our funding formulas and getting the congressional budget office and the office of management of budget in the executive agency to tilt the scale towards those communities that come up with plans that work for them for the risks that they are facing and are actually achievable.

Josh Sewell:

I think one example, we started this talking about hurricanes, is that I read this week that only 35% of jurisdictions out there have the most up-to-date building codes. We saw a real example, and you may be able to speak to this more because you worked on it, is that after Hurricane Andrew, I mean, Florida changed a lot of its building codes, and so actually now, if you are building houses in Florida, they’re built to better withstand hurricane-force winds and they have to be that way because it became a requirement. Similarly, in California and other earthquake-prone areas, you have to construct your buildings to withstand earthquakes because we know that’s going to happen. The big thing is it costs more money to do that. It’s true. It costs more money to build a house and to higher standards. It costs more money is for communities to build themselves towards better standards. But we save a lot of money by having less disaster response and having less costs, and again, you also can save lives.

Steve Ellis:

Right, and we recognize that the building code for Florida isn’t the building code for Michigan, which isn’t the one for Texas, which isn’t the one for California, so it’s not even having a national building code, or even a floor, it’s just that making sure that you have a building code that is strong for the risks that that community particularly faces, and so that’s something that we’ve supported our entire existence.

Steve Ellis:

Now, Josh, we talked a bunch about the funding and about making sure it’s going to the right places, but one of the real challenges that we’ve found over the years is actually following the money and tracking this funding that the federal government doesn’t seem to always want to know where their money went or when it went, or what is being funded, so can you talk a little bit about that, about the issues of tracking the funding, and some of the challenges that we face?

Josh Sewell:

Yeah, one of the unfortunate things about disaster spending is that agencies often don’t even try to track it, so unless the appropriations bill, the spending bill requires the agencies to separate the tracking for those emergency dollars compared to their base budget dollars, they sometimes don’t do it.

Josh Sewell:

As an example, I know actually recently the Department of Transportation inspector general did a report on the Federal Transit Administration, so talking mass transit for the most part, and one of the reports that they did showed that after Superstorm Sandy, the FTA had received $10 billion in funds to help with recovery. Now, remember this was in the fall of 2012 is when this happened and the money really got out the door by the beginning of, I think it was in January 2013. By the end of 2022 only $4.3 billion had actually been spent, so you’re talking $5.7 billion, almost 60% of the funds eight years later, seven years later, has not been spent. Why not is a good question. There may be various reasons, but even figuring out where that money was or where that money is difficult because the agency wasn’t actually tracking those dollars separate from its other dollars.

Josh Sewell:

The reason you need to track disaster spending different separately from other spending is because it’s for a different purpose, and as you mentioned earlier, there’s often less oversight initially because if you were around and we were during the debate around Superstorm Sandy is there was an attempt to slow down some of that emergency spending at the beginning to say, “How much do we really need? Do we really think we need $60 billion for all the various things?” Folks who said, “Let’s slow this train down,” were pilloried and just basically ran over eventually by the folks who wanted that money.

Josh Sewell:

Yet here we are 10 years later and there still is money unspent from Superstorm Sandy, so that means either we didn’t need that money or we directed that money into the wrong uses, and so that’s something that we have to actually be honest about in these debates is that absolutely we want to help in response, but money itself doesn’t actually solve all the problems because, I mean, money doesn’t magically fill sandbags. Having the money doesn’t actually get the boats in the right places. You actually have to have these resources and you have to make sure they’re going where they’re needed because otherwise it’s a waste of time and it’s a waste of money and it’s a waste of opportunity.

Steve Ellis:

Yeah, recovery doesn’t happen overnight. I mean, certainly the disaster can happen pretty much overnight or within a couple days. But the recovery is years in the making and that’s why you should be allocating these funds and even have clawbacks or ways that you can meet it out or have triggers for the funds to be released at a later date because they talk about a fog, or there’s a fog of disaster, and you don’t know whether, you know what all the needs are, you know the needs are great, and certainly, the politicians are there, and their big thing is that strike while the iron’s hot, get all you can, and that the time that the people are the most sympathetic to their needs is right after the disaster.

Steve Ellis:

But the reality is that it’s going to take years to rebuild in these areas, or to remake these communities, and do it in a smart way, and yet there’s always a push to get all as much cash as you can, and not a lot of tracking afterwards. That’s certainly what Taxpayers for Common Sense, what we’re doing is trying to follow those dollars and make sure the money is being spent well because we’re not doing anybody a service if the money is wasted.

Steve Ellis:

I guess that gets to my last point that I want talk about. I mean, taxpayers are heavily invested in disaster response and recovery. Really, What do taxpayers deserve? What does Uncle Sam owe our taxpaying public, our Budget Watchdog AF listeners, what do they owe them with this huge amount of money that goes out in disaster response?

Josh Sewell:

We’re owed good policy. Taxpayers deserve to have disaster policies that work, that save lives, and make us more prepared for the future. One of the more important things to understand is that disasters are going to happen. We can’t stop a hurricane, you can’t stop a flood, these events are going to occur, and so we can learn lessons from what has worked and what has not worked in the past. In my opinion, that is the biggest shortcoming in our federal disaster policies is that we don’t have baked into it a requirement that we look back and say, “What did work? What didn’t work? Did we have enough money to respond? Did we have enough money to do good mitigation? Is this community that was devastated by this disaster? Is it now better prepared for the next time that tornado occurs? Is it better prepared for the next time that hurricane occurs? If so, let’s take those lessons learned and show other communities and encourage them to make themselves better prepared.”

Josh Sewell:

I think that’s the biggest thing for me is we know these are going to happen, disasters, they aren’t anomalies. I mean, sure, I mean, odds are a tornado’s not going to hit the same town every year, but it’s going to hit somewhere, so let’s figure out what works, what doesn’t work. I think that means we ultimately need better budgeting, diligent preparation, and a sober review of communities and the federal government’s performance. That’s before, during, and after disasters. That’s how you save dollars, and again, the most important thing is that’s how you save lives.

Steve Ellis:

Thanks, Josh. Really well-said. There you have it, listeners. Vicious cycles can afford quiet opportunity when taxpayers are prepared, really prepared. This is the frequency market on your dial, subscribe and share, and know this, Taxpayers for Common Sense has your back, America. We read the bills, monitor the earmarks, and highlight those wasteful programs that poorly spend our money and shift long-term risk to taxpayers. We’ll be back with a new episode and I hope you’ll meet us right here.