Despite adding over $156 billion in Pentagon spending in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) earlier this summer, Congress has not hesitated to continue its tradition of proposing hundreds of “program increases” to the Pentagon budget for the coming fiscal year through the regular appropriations process. In funding tables accompanying the FY2026 House and Senate draft Pentagon appropriations bills, lawmakers proposed 1,403 program increases for Pentagon Procurement and Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) accounts, at a total cost of $52.2 billion. Our updated sortable database of congressional Pentagon budget increases catalogues each and every one of these funding proposals.[i]

Congress doesn’t call these increases earmarks, but they serve a similar function—allowing lawmakers to channel money to favored projects that often benefit their states, districts, and campaign contributors. The main distinction is that these increases are supposed to be competitively awarded, or at least awarded for projects that received competitive awards in the past. But in practice, the increases are often so specific that only one contractor is positioned to secure them. And for those increases going to projects that were, at least nominally, competitively awarded in the past, lawmakers are fully empowered to direct funds to specific companies, even when PACs and individuals associated with those companies have contributed to their campaigns.

Another distinction is that, unlike formal earmarks, program increases don’t come with any transparency or justification requirements, leaving taxpayers largely in the dark as to who proposed which increases and why. When it comes to formal earmarks, according to Senate rules summarized on a Senate Appropriations Committee webpage, Senators who submit requests for earmarks must “certify that neither they nor their immediate family members have any financial interest in the item(s) requested, and the Committee will post a list of the requests and certifications on its website.” Under House rules, Representatives are limited to ten earmarks, must post all requests online in a searchable format, must demonstrate community support, must only request funds for state or local governments or eligible nonprofits, and must certify that neither they nor their immediate family have a financial stake in the request. No such requirements exist for program increases to the Pentagon budget.

In light of the growing cost of these backdoor earmarks, as well as a clear potential for conflicts of interest, Congress should require at least the same level of transparency and accountability for program increases that it requires for formal earmarks.

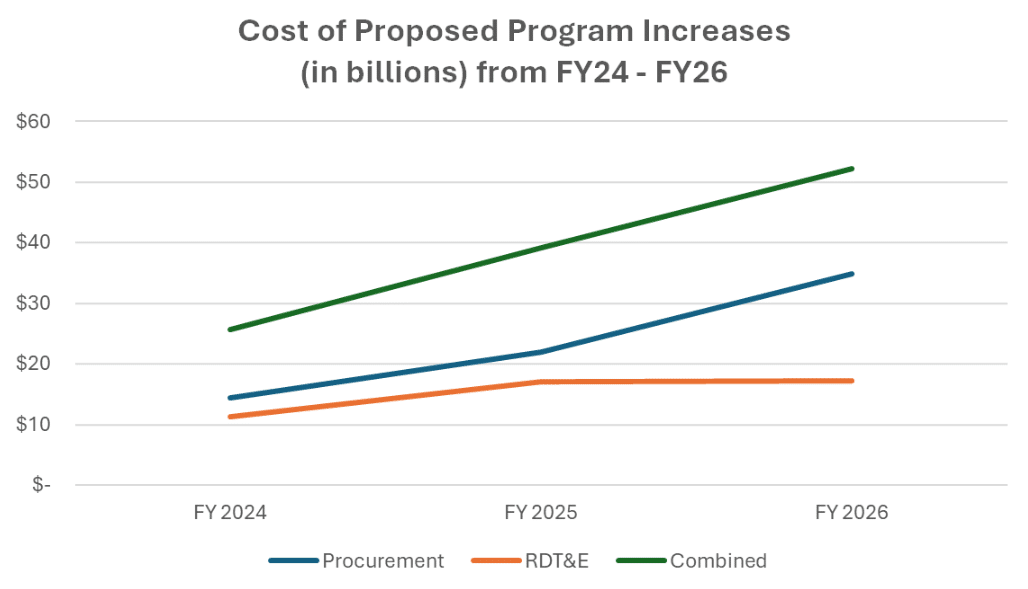

Cost of Proposed Increases Double in Two Years

Even excluding the Pentagon spending increases included in OBBBA, the cost of proposed increases to the Pentagon’s Procurement and RDT&E accounts in base appropriations bills has been rising at a dramatic rate.

For the purpose of tracking trends in the cost of these increases, it’s important to note that the House and Senate each draft their own versions of the Pentagon spending bill, which advance on separate tracks until their differences are reconciled in conference and voted on as a single bill. The House Appropriations Committee advanced its version of the bill on June 16, 2025, and the full House passed it with amendments on the House floor on July 18, 2025. The Senate Appropriations Committee advanced its version of the bill on July 31, 2025. As of this writing, the Senate has not brought its version of the bill to the floor for a vote, and there’s little reason to suspect it will. In ten of the last ten years, Senate leadership has not held a floor vote on their version of the bill. If that trend continues, rank and file Senators will not get the chance to vote until the final conference bill comes to the floor. In the conferencing process, some of the proposed increases are usually dropped from the bill. As we are still waiting for the final FY2026 bill, this analysis focuses on trends in the proposed increases in the House and Senate draft bills from FY2024 to FY2026.

As this chart shows, the cost of proposed increases for Procurement and RDT&E more than doubled in just two years, jumping from $25.68 billion to $52.2 billion. While the cost of proposed increases for both Procurement and RDT&E rose from FY2024 to FY2025, the cost of proposed RDT&E increases leveled off from FY2025 to FY2026. However, the cost of proposed increases for Procurement rose at a sharper rate over that period, effectively keeping the combined growth rate constant.

Interestingly, the number of proposed increases dropped slightly from 1,499 in FY2025 to 1,403 in FY2026, though they’re still up from 1,216 in FY2024. But the slight drop in the number of increases alongside a major increase in the cost led the average cost per increase to rise by an even higher margin than the overall cost.

While the total cost of increases in the final bill will likely be less than the combined cost of proposed increases in the draft bills, how much less is difficult to say. In FY2024, the final Pentagon spending bill included $21.27 billion in increases for Procurement and RDT&E, down from $25.68 billion in the House and Senate drafts. But in FY2025, due to a combination of budget caps imposed by the Fiscal Responsibility Act and a full-year continuing resolution, both of which limited increases to the Pentagon’s topline, the total cost of Procurement and RDT&E increases dropped from $39.16 billion in the House and Senate drafts to $14.95 billion in the final bill. If Congress opts to fund the government through another full-year CR, as some lawmakers have proposed, that might serve to limit the number and cost of program increases included in the final bill. But even in the event of a full-year CR, Congress may choose to include anomalies, or exceptions to otherwise flat spending levels, which could allow the bulk of the program increases to move forward.

Whatever happens in the final bill, the data on proposed increases underscores the potential for costs in the final bills to spiral at similar rates in the coming years.

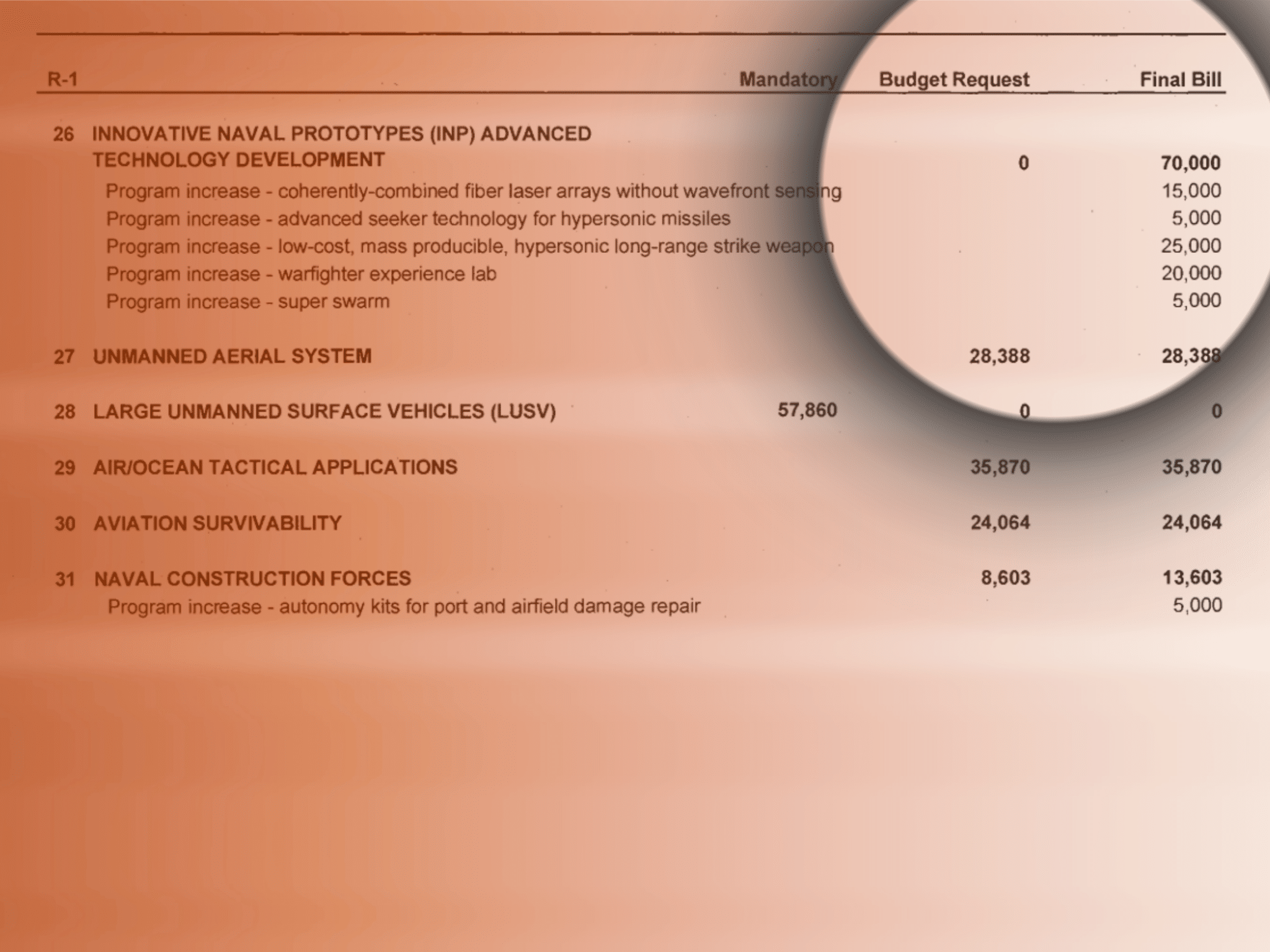

Zero to Hero

In some cases, program increases for Procurement and RDT&E appropriate additional funds for projects that were included in the Pentagon’s budget request. In other cases, program increases fund projects that the Pentagon did not fund at all in its request. We call these “Zero to Hero” increases.

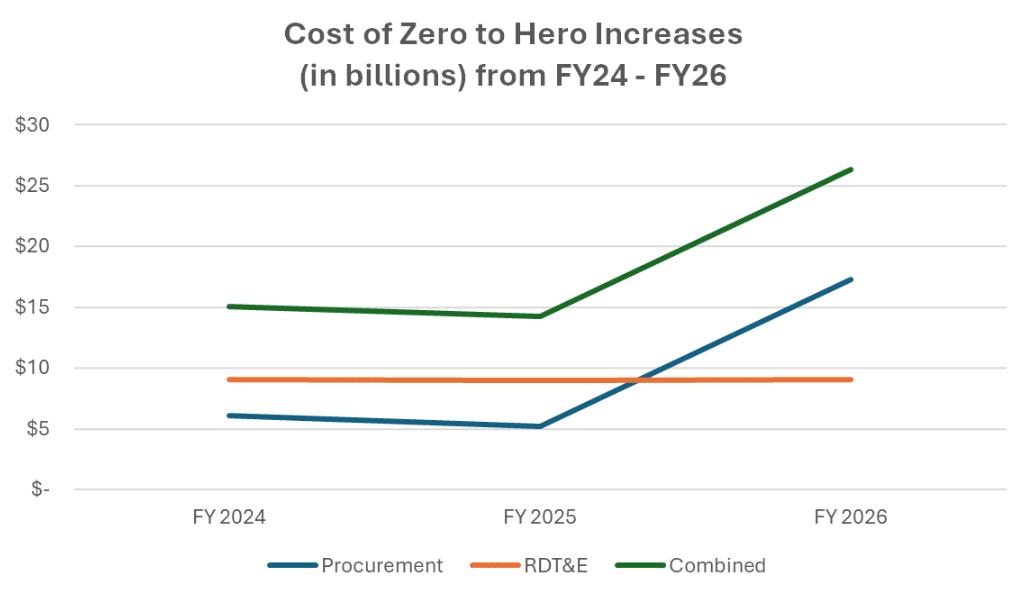

To identify them, we cross reference the proposed increases with thousands of pages of justification books that the Pentagon includes in its budget submission to Congress each year. These J books, as they’re often called, detail spending plans at the project level. If a proposed increase isn’t mentioned in the justification books under the program element for that increase, we mark it as Zero to Hero. The following chart shows the cost of proposed Zero to Hero increases for Procurement, RDT&E, and combined, from FY2024 to FY2026.

Driven almost entirely by a major increase in the cost of proposed Zero to Hero increases for Procurement, the cost of proposed Zero to Hero increases across Procurement and RDT&E rose from $14.23 billion in the House and Senate drafts for FY 2025 to $26.33 billion in the FY 2026 drafts, an 85 percent increase. Within Procurement, the costs ballooned from $5.2 billion to $17.31 billion, a 233 percent increase. This shows that Congress sought funding for unrequested procurement projects far more aggressively in FY2026 than it did in the previous two years.

As a percentage of the total cost and number of proposed program increases for Procurement and RDT&E, Zero to Hero increases accounted for 50 percent of the cost and 75 percent of the number of increases in FY2026. That’s compared to 36 percent of the cost and 72 percent of the number of proposed increases in FY2025, and 59 percent of the cost and 83 percent of the number in FY2024.

Unfunded Priorities

Since 2017, Congress has required the military services and combatant commands to submit so-called Unfunded Priority Lists (UPLs), wish lists for funding not included in the formal budget request. We’ve long opposed this practice, which subverts the normal budget process, circumvents civilian control over the Pentagon budget request, and undermines actual priorities included in the budget request. The amount of tax dollars requested through these lists has tripled since FY2024, growing to over $53 billion this year. However, the similarity in the cost of UPLs and the total cost of proposed increases for Procurement and RDT&E is a complete coincidence. That’s partly because UPLs include requests for Military Construction funding, which our database does not track. But it’s also because UPLs make up a relatively small proportion of the overall number and cost of program increases for Procurement and RDT&E.

Our database shows that only 43 of the total 1,403 proposed program increases for FY2026 appeared to respond to UPLs—just over 3 percent.

This is relevant in part because proponents of the congressional practice of adding hundreds of program increases to the Pentagon budget each year have pointed to UPLs to suggest that Congress is merely responding to needs identified by the military. In response to questions about our FY2024 data on program increases, a Senate Appropriations Committee staffer told Roll Call that “These increases include unfunded requirements of DOD and adjustments DOD asked for following the submission of the budget request to account for inflation or emergent requirements.” But as the data shows, UPLs are not the primary force driving these increases. And inflation certainly can’t account for the costs of these proposed increases doubling in two years.

That said, UPLs still make up a significant amount of the cost of the program increases for Procurement and RDT&E—about $9.6 billion of the $52.2 billion in increases (18.4 percent) appeared to respond to UPLs. That’s not nearly enough to support claims that Congress largely offers program increases in response to the military’s stated needs, but it does further the case for bipartisan legislation to repeal the statutory requirement for UPLs.

Funding Offsets

While Congress has proposed adding over $52 billion in program increases for Procurement and RDT&E, many of these increases are offset by corresponding cuts within the Pentagon budget. Most of these tradeoffs happen behind closed doors in the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, making it impossible for the public to discern what was cut to make room for each program increase. However, the House of Representatives often allows floor amendments to its pre-conference version of the Defense Appropriations Act before it passes, offering non-appropriators a bite at the apple (the Senate, in contrast, hasn’t made time for floor amendments on its version of the Pentagon spending bill in at least the past decade). Unlike the program increases proposed in committee, program increases offered as amendments list their sponsors and their offsets, offering a glimmer of transparency in an otherwise opaque process.

Lawmakers often view offsets as a means of securing their priorities without adding to topline budgets, but offsets are essentially would-be budget cuts that could be used to reduce federal spending, pay down the debt, or simply return money to taxpayers. Instead, lawmakers are essentially making the case that their favored projects are more important than saving money, or than the pot of funding their increase would siphon from.

In total, lawmakers in the House adopted 274 amendments for program increases, with a total cost of $2.18 billion. Of those 274 amendments, 150 were paid for with cuts to RDT&E accounts, 109 with cuts to Operations and Maintenance accounts, and 15 with cuts to Procurement accounts. The RDT&E cuts totaled $1.24 billion, O&M cuts totaled $803 million, and Procurement cuts totaled $139 million.

One of the problems with this approach is that lawmakers tend to be far less prescriptive in their offsets than their increases. Most of the proposed offsets listed in amendments for program increases simply cut funds at the account level, e.g. “O&M, Defense-Wide,” meaning the Pentagon’s department-wide Operations and Maintenance Account. Some get slightly more specific, e.g. the Army’s “Other Procurement” account, one of several procurement accounts within the Army’s budget. Vanishingly few make cuts at the program level. In effect, this practice allows either the conference committee that reconciles differences between the two bills, or the Pentagon itself, to decide which programs or projects to cut from each of the offset accounts. Either way, there’s no transparency about these decisions. And if they are left up to the Pentagon, then this would represent yet another example of Congress ceding its power of the purse to the executive branch.

Another problem is that cuts to O&M in particular can have a serious impact on readiness. Operations and Maintenance accounts are essential, ensuring equipment works, facilities are maintained, and more. While there is no transparency over specific offsets for program increases proposed in committee, a 30,000-foot view of the Pentagon budget offers some clues.

In its FY2026 budget request, the Pentagon asked for about $337.6 billion in discretionary funding across all O&M accounts, and for an additional $22.7 billion for O&M in mandatory funding through budget reconciliation, for a total of about $360.3 billion. Congress categorizes O&M funding differently than the White House, so according to Congress, the White House actually requested $295.7 billion in discretionary funding. The House’s draft bill would appropriate $283.3 billion in discretionary O&M spending, while the Senate’s would appropriate $302.8 billion. If the lower House version were adopted, that would constitute a $12.4 billion cut.

As for O&M funding included in OBBBA, the Republican budget reconciliation bill, the funding tables that Congress sent the Pentagon (which lack much of the detail included in traditional funding tables) only direct about $8 billion in funding for O&M, compared to the Pentagon’s request for $22.7 billion. That means if Congress adopts the House’s proposed funding levels, O&M funding for FY2026 could come in up to $27.1 billion below the Pentagon’s request.

The Pentagon has some $271 billion in deferred maintenance costs as of 2024—which is part of why stories of derelict military housing and black mold at military installations abound. Congress raiding O&M to pay for pet projects in Procurement and RDT&E isn’t helping.

A third problem is that almost all of these amendments passed by voice vote en bloc, meaning as part of a package of amendments, with no debate, and no opposition. Despite their cumulative price tag of $2.18 billion, because their cost was offset, they’re viewed as noncontroversial. Most lawmakers voting for these amendments probably didn’t read them. And these are the more transparent form of program increases, relative to those offered behind closed doors in committee. It’s a grotesquely cavalier way to budget for national security.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Unlike the program increases offered as amendments, the bulk of the program increases added to the Pentagon spending bill each year do not list their sponsors. But some lawmakers aren’t shy about claiming credit for them, even when the likely recipients of these increases contributed to their campaigns. In some cases, lawmakers or their families even hold stock in companies that will benefit from the increases they secure.

$360 Million for AH-64E Apache Helicopters

In a press release celebrating the Senate Appropriations Committee’s advancement of the FY2026 Pentagon spending bill, Sen. Katie Britt (R-AL) took credit for ten “significant program increases and priorities in this legislation to invest in Alabama’s defense capabilities.” Among them was a $360 million program increase “to procure additional 12 AH-64E aircraft, supporting work in Huntsville.” In the funding tables for the Senate’s Pentagon spending bill, there’s a $360 million increase for “AH-64 reman aircraft.”

While the Pentagon budget request included about $1.7 million for the program element for these aircraft, the justification book for Army Aircraft Procurement explained that the funding “supports production line activities, airworthiness, and safety support of AH-64E Remanufacture aircraft delivered.” It then stated, “FY 2025 to FY 2026 funding decrease due to prioritization and leadership decisions to decrease funding related to AH-64E Remanufacture production.” In other words, the Pentagon made a conscious decision to zero out funding for new AH-64 Apache helicopters this year.

AH-64 Apache helicopters are manufactured by Boeing at facilities in Mesa, Arizona and Huntsville, Alabama. According to OpenSecrets.org, a nonpartisan independent nonprofit that spotlights money in politics, individuals and PACs associated with Boeing contributed a total of $31,406 to Sen. Britt’s campaign committee and leadership PAC during the 2022 and 2024 election cycles.

$88.5 Million for Shop Equipment Contact Maintenance Vehicles

Sens. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) issued a joint press release on the Senate Appropriations Committee’s passage of several appropriations bills, including the Pentagon spending bill. Underscoring the lack of a meaningful distinction between formal earmarks and program increases, it notes that “Durbin and Duckworth worked to secure various priorities for Illinois in the appropriations bills, both through Congressionally Directed Spending requests and through the programmatic appropriations process.” Congressionally Directed Spending is the Senate’s rebranded term for earmarks, while the House now refers to earmarks as Community Project Funding.

Under the heading of “Rock Island Arsenal,” a military installation in Illinois, the release goes on to highlight “$88.5 million to continue manufacturing of Shop Equipment Contact Maintenance Vehicles (SECM) as part of the AM-General/RIA partnership.” In the Senate’s funding tables, there’s an $88.5 million increase for “Next generation HMMWV shop equipment maintenance vehicle.”

As the release indicates, the next-generation Shop Equipment Contact Maintenance vehicle is manufactured by AM General at Rock Island Arsenal. According to OpenSecrets.org, individuals and PACs associated with AM General Corp contributed $32,500 to Sen. Durbin’s campaign committee and leadership PAC from 2019-2024. While AM General was not listed by OpenSecrets.org in Sen. Duckworth’s top 100 contributors, individuals and PACs associated with AM General’s parent company KPS Capital Partners contributed $42,750 to Sen. Duckworth’s campaign committee and leadership PAC from 2019-2024. KPS Capital Partners was not listed among Sen. Durbin’s top 100 contributors.

$282.5 Million for F-135 Engine Core Upgrade

Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME), the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, issued a press release announcing that “she secured significant funding and provisions for Maine” in the Pentagon spending bill. In it, she highlighted $282.5 million for the F-135 Engine Core Upgrade, an upgrade to the engine for the F-35 fighter jet. Pratt & Whitney, a subsidiary of RTX (formerly Raytheon), leads the F-135 Engine Core Upgrade program.

According to OpenSecrets.org, individuals and PACs associated with RTX contributed $65,649 to Sen. Collins’ campaign committee and leadership PAC from 2019-2024. According to financial disclosures, Sen. Collins’ husband also owns $50,000 worth of stock in RTX. Had this been a formal earmark, Senate rules would have required Sen. Collins to certify that neither she nor her immediate family have any financial stake in the request. But as this was a program increase, Sen. Collins was under no such obligation.

$5 Million for Next Generation Combat Vehicle Prototype

Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) also issued a press release following the advancement of the bill, celebrating “measures led and supported by Peters…” Among those measures, the release touts $5 million “to support Michigan State University’s (MSU) collaboration with the U.S. Army to build a prototype of a lightweight autonomous vehicle platform to fuse different technologies into a unified system.” The funding tables for the bill included a $5 million increase for “Lightweight prototype” under the Army’s Next Generation Combat Vehicle Technology program element. According to OpenSecrets.org, individuals associated with Michigan State University contributed $177,121 to Sen. Peters’ campaign committee and leadership PAC from 2019-2024.

Conclusion

In FY2026, national security spending will surpass $1 trillion for the first time, and interest payments on the nation’s debt will surpass $1 trillion for the second. While lawmakers have defended program increases to the Pentagon budget as vital for national security, many of the increases in the Pentagon spending bills appear to be designed to benefit the states, districts, and campaign contributors of their authors. But the two are not mutually exclusive. Many of the increases, including those for which we’ve highlighted potential conflicts of interest, may have real national security benefits, and may warrant funding.

Furthermore, the Constitution vested Congress with the power of the purse as a critical check on executive power. As such, it is Congress’ prerogative to add and subtract funds from the Pentagon budget as it sees fit. But nothing in the Constitution suggests Congress should make these decisions in the shadows. Apart from classified adjustments, taxpayers deserve to know the purposes—and the authors—of increases to the Pentagon budget.

Whether through a legislative fix, or direct changes to House and Senate rules, Congress should require lawmakers to attach their name to the program increases they propose in the Pentagon budget, and offer details on their purposes, long-term costs, and offsets. Without these requirements, lawmakers will continue adding tens of billions of dollars to the Pentagon budget for reasons unknown, and both taxpayers and national security will continue paying the price.

This article has been updated to correct a mischaracterization of congressional spending proposals for Operations and Maintenance (O&M) stemming from differences in how the White House and Congress define O&M funding.

[i] When Congress passes the final Pentagon spending bill for FY 2026, we’ll update the database to reflect the inclusions in the final bill.