The President’s FY2018 ‘Skinny Budget’ Analysis

With 20 years of experience, TCS staff will be combing through the President's fiscal year (FY) 2018 'skinny' budget and posting our observations and analyses on this page in a continuously updated blog.

March 17, 2017

3:05pm – Counter-productive Cuts at IRS

3:05pm – Counter-productive Cuts at IRS

2:10pm – A Word About "Rounding" and Secrecy

2:10pm – A Word About "Rounding" and Secrecy

11:35am – Pentagon Skinny Budget Request

11:35am – Pentagon Skinny Budget Request

March 16, 2017

4:45pm – DOE: Research and Development

4:45pm – DOE: Research and Development

3:15pm – Regional Development Commissions

3:15pm – Regional Development Commissions

2:40pm – Give Me the Cash; You Find the Cuts

2:40pm – Give Me the Cash; You Find the Cuts

2:30pm – Mum on the Coast Guard

2:30pm – Mum on the Coast Guard

1:45pm – TCS Statment on the FY2018 Budget

1:45pm – TCS Statment on the FY2018 Budget

Stay tuned for live developments as we comb through the details of the FY2018 'skinny' budget.

March 17th, 3:05pm

Counter-productive Cuts at IRS

The skinny budget wants to "ensure that the IRS could continue to combat identity theft, prevent fraud, and reduce the deficit through the effective enforcement and administration of tax laws." But to achieve that the budget reduces the IRS budget by $239 million, which would be a 4.9 percent reduction of the enforcement account over FY16 levels. That is a disproportionate cut than what was for the Department of Treasury overall (4.1 percent).

Obviously we don't know the details of how the cut would be meted out. But the IRS is a popular bad guy for lawmakers and the public alike and their budget shows it. Obviously, the agency need to be effectively and efficiently run, but at the same time cuts to their budget – which have been going on for years – both negatively effects their ability to work with and help the public and reduces enforcement actions which help maintain confidence in our nation's voluntary tax system.

March 17th, 2:10pm

A Word About "Rounding" and Secrecy

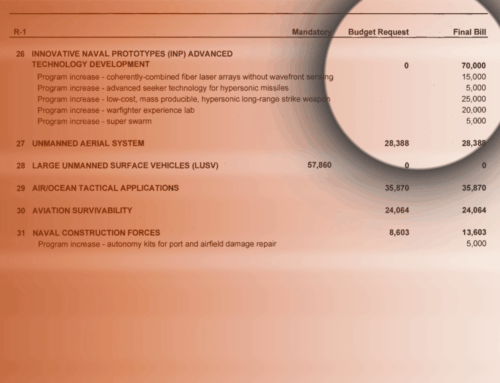

Interestingly the lists of procurement and research and development programs, presented by the Pentagon Office of the Comptroller to explain the overall Fiscal Year 2017 supplemental request, don't tell the whole story.

Naturally there are always details that are kept secret in any Pentagon funding request. But what's interesting about this is the staggering difference in how much detail the different parts of the Pentagon are willing to put on the table.

The Department of the Navy (which includes both the Navy and Marine Corps) are the most open. Of the $5.8 billion in additional program funding, they fully disclose $4.973 billion of it.

The Army is the next most willing to show its cards: of $4.6 billion, they released details on $3.453 billion.

Next is the Air Force. Of $4.1 billion, its publicly disclosed list adds up to only $2.18 billion.

And the biggest secret keeper is, not surprisingly, the Special Operators. Of the $1.0 billion additional money for "Defense-wide," which is dominated by Special Operations Command, only $476 million is disclosed. And while in pure dollar figures that means only $524 million is kept secret, that translates to 52% of the requested plus-ups being classified.

More things that make you go, "Hmmmmm."

March 17th, 2:05pm

What's in the Supplemental for the Air Force?

So what does the Air Force get from this latest largesse, should the Congress agree to this supplemental request? Of the combined total for procurement and R&D of $15.5 billion across the supplemental request, the Air Force receives an increase of $4.1 billion. And from that total the Air Force is able to purchase or upgrade a number of systems.

For instance, among others these programs get a boost:

– 5 additional F-35 fighters for $596 million

– 5 additional HC/MC-130 aircraft for $500 million

– Modifications for the F-16 for $160 million

– Modification for the C-130 for $137 million

– Unspecified "vehicles" for $361 million

– Unspecified "bombs" for $60 million

– Physical Security Equipment for $145 million

– Explosive Ordinance Disposal Equipment for $221

And here we find the additional F-35 request that no Pentagon appropriation is whole without. At TCS we had high hopes that this President, in his zeal for a better deal on fighter aircraft, might put the brakes on this monstrously expensive program.

Alas, no.

March 17th, 1:50pm

What's in the Supplemental for the Navy?

So what does the Department of the Navy get from this latest largesse, should the Congress agree to this supplemental request? It is important to point out the Department of the Navy includes two military services: the Navy and the Marine Corps. So, of the combined total for procurement and R&D of $15.5 billion across the supplemental request, the Navy and Marine Corps split an increase of $5.8 billion. And from that total the two services are able to purchase or upgrade a number of systems.

For instance, among others these programs get a boost:

– 24 additional F/A-18 E/F Super Hornets for $2.3 billion

– 2 additional V-22 Tilt-Rotor Aircraft for $171 million

– Modifications to the V-22 for $99 million

– 6 additional P-8 patrol aircraft for $920 million

– 2 C-40A aircraft for $208 million

– 96 Tomahawk missiles for $85 million

– $43 million more for Standard missiles

– Completion of one Arleigh Burke class destroyer for $433 million

– 515 Javelin missiles for $77 million

Interestingly, although close to $3.5 billion is spent on new aircraft, neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps seems to have requested additional F-35 fighter jets.

File that under: Things that make you go, "Hmmmmmm."

March 17th, 11:45pm

What's in the Supplemental for the Army?

So what does the Army get from this latest largesse, should the Congress agree to this supplemental request? Of the combined total for procurement and R&D of $15.5 billion, the Army hauls in a respectable $4.6 billion. And from that total they are able to purchase or upgrade a number of systems.

For instance, among others these programs get a boost:

– 13 Predator unmanned aircraft for $130 million

– Modifications to Shadow unmanned aircraft for $248 million

– 20 Apache helicopters for $708 million

– 17 Blackhawk helicopters for $376 million

– 1188 Guided MLRS rockets for $155 million

– 591 Javelin missiles for $104 million

– Upgrades to 27 Abrams tanks for $330 million

– Modifications to Patriot missile systems for $228 million

March 17th, 11:40pm

What, Exactly, is in the Pentagon's Fiscal Year 2017 Supplemental Request?

Details are trickling out from the Administration's Fiscal Year 2017 Supplemental request for the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security. You can read the transcript of yesterday's Pentagon press briefing on the request.

At the Pentagon, the largest tranche of money in the $30 billion supplemental request is for procurement programs ($13.5 billion) and there is also a healthy increase to the research and development (R&D) accounts ($2 billion.)

We'll be posting a short series of analyses showing what the military departments get out of this request, so keep checking back here.

March 17th, 11:35am

Pentagon Skinny Budget Request

The Fiscal Year 2018 skinny budget submission from the Office of Management and Budget definitely puts all the Washington budget nerds (like us!) on a diet when it comes to details. But while other federal departments may be starving for cash if this budget is passed as is, the Pentagon is living off the fat of the land. They're in tall cotton. They're bingeing. They're…well, we've run out of metaphors for how much better the Pentagon budget has it compared to other agencies.

The total request for FY18 is $639 billion broken down to $574 billion for the "base budget" and $65 billion for the so-called Overseas Contingency Operations or OCO account.

For comparison, President Obama's last full budget request, for Fiscal Year 2017, asked for roughly $524 billion in the base budget and a little less than $59 billion for OCO.

The long-term conceit is that the OCO budget is used exclusively to fight the nation's wars and other operations on foreign soil while the base budget does everything else. We say "conceit" because over the years we've pointed out plenty of times that the OCO account was blatantly used to fund domestic Pentagon priorities.

Once you get past these topline numbers, the skinny budget details are thin on the ground. Thin and platitudinous:

"Addresses urgent warfighting readiness needs."

"Begins to rebuild the U.S. Armed Forces…"

"Lays the groundwork for…"

"Initiates an ambitious reform agenda…"

See what we mean? Platitudes but not a lot of tables and data for budget nerds to get our teeth into. In particular, there is no way for us to look at the base budget versus the OCO budget to see if this Administration is holding the line on keeping domestic priorities out of the OCO request. The FY17 Supplemental Request for the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, see further analysis below, does a good job of differentiating between the base budget and the one for warfighting.

At TCS we hope this is a trend that continues. Once we have more details on the FY18 request, we'll be digging in and writing and talking about it.

March 16th, 4:45pm

DOE: Research and Development.png)

The budget proposes making cuts to the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, the Office of Nuclear, Energy, the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability, and Fossil Energy Research and Development. While the proposal is light on details, we have raised concerns with R&D spending at DOE going to mature energy technologies that should pay their own way. The Fossil Energy R&D program, funded at $632 million in FY2016, has been used for years to underwrite development of technologies like carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) that are unproven, and from which private industry would overwhelmingly benefit. The Nuclear Energy R&D program, funded at $533 million in FY2016, also subsidizes the well-established nuclear industry by conducting research and development on their behalf. The budget and the administration seem to recognize this by proposing to shift what remains of the R&D budget towards investment in sciences at the more fundamental level.

March 16th, 4:40pm

The Department of Energy Loan Program Office

The FY 2018 request proposes eliminating all funding for the Title XVII Loan Guarantee Program and the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing (ATVM) Program.

The Title XVII Program, which was first created in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and expanded in the 2009 Stimulus, puts the full faith and credit of the United States on the line for a range of energy projects including renewable, nuclear, and advanced fossil fuels. In 2014, the program awarded its largest award of more than $6 billion in loan guarantees for the construction of nuclear reactors 3&4 at Plant Vogtle in Georgia without charging the beneficiaries a single dollar in credit subsidy cost. The program suffers from a lack of transparency and allows applicants to remain eligible for a guarantee regardless of how dire their financial state becomes, locking taxpayers to massive boondoggles. This and other structural flaws have caused taxpayers to lose hundreds of millions already, but the totals could quickly skyrocket.

The ATVM program, which was created in the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 and provides direct loans to auto producers or suppliers, has also invested and lost taxpayers' money on risky projects. Of the five loans made by the ATVM program, two have defaulted. One, for Fisker Automotive, cost taxpayers more than $200 million. The ATVM also suffers from similar problems to Title 17 and has been criticized by the Government Accountability Office and others.

March 16th, 4:35pm

Dramatic Shift in Department of Energy Funding

.png)

As with the budget for other agencies, details about what the President wants to fund within the Department of Energy (DOE) are scant. Specifically, how the administration wants to spend $28 billion for DOE is outlined in roughly 600 words on one and a half pages. That's comparable to the DOE section in the last "skinny budget" in 2009, but infinitesimal compared to the information provided in a typical DOE budget request – the FY 2017 request was more than 3,000 pages divided among six volumes and supplemental materials. Those documents, furthermore, provide some of the only public information about the thousands of DOE projects and programs. Working with what we've got, here's what we do know from the President's FY 2018 DOE budget:

- Overall DOE funding is cut, but the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) budget, which typically makes up around 40 percent of DOE's budget, is increased. As a result, funding for non-NNSA programs in DOE is cut dramatically. (See chart below)

Department of Energy Funding – FY 2008-2018

| Fiscal Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| NNSA | |||||||||||

| Request | 9,387 | 9,097 | 9,945 | 11,215 | 11,783 | 11,536 | 11,652 | 11,658 | 12,565 | 12,884 | 13,900 |

| Enacted/Actual | 8,895 | 9,222 | 9,887 | 10,526 | 11,000 | 10,576 | 11,207 | 11,399 | 12,527 | 12,500 | |

| Non-NNSA | |||||||||||

| Request | 14,872 | 15,918 | 16,449 | 17,190 | 17,764 | 15,619 | 16,763 | 16,282 | 17,358 | 19,615 | 14,100 |

| Enacted/Actual | 15,780 | 61,359 | 17,224 | 15,167 | 15,300 | 14,562 | 16,018 | 16,003 | 17,076 | 17,200 | |

| DOE Total | |||||||||||

| Request | 24,259 | 25,015 | 26,394 | 28,404 | 29,547 | 27,155 | 28,416 | 27,940 | 29,924 | 32,499 | 28,000 |

| Enacted/Actual | 24,675 | 70,581 | 27,111 | 25,693 | 26,300 | 25,137 | 27,225 | 27,402 | 29,603 | 29,700 |

- Without knowing where the extra money for the NNSA is being directed, it's hard to say whether the significant increase (11%) is justified or not. As proposed, the NNSA would account for 50% of DOE's budget.

- The skinny budget does provide some description of where the non-NNSA cuts will come from, and the list includes some items that TCS has urged Congress and the President to cut for years:

- The DOE Loan Program Office

- Research & Development funding for established industries

March 16th, 3:15pm

Regional Development Commission

Among the litany of independent agencies the budget proposes eliminating are the three regional development commissions – the Appalachian Regional Commission, the Denali Commission, and the Delta Regional Authority. TCS applauds elimination of these three commissions.

Over the last 50 years, Congress has funneled billions in appropriations to these commissions in the guise of combating poverty and economic underperformance. But by acting as unnecessary middlemen and mismanaging funds, the commissions have become inefficient and ineffectual anachronisms. Each of the commissions have exhibited a number of administrative failures that have undermined their efforts to deliver relief to economically distressed areas.

The Appalachian Regional Commission has chronically mis-prioritized its assistance, often helping the well-connected rather than the truly distressed, and thrown money away on a number of questionable projects. The Denali Commission has funneled the money it gets straight to a handful of contractors or state agencies, without apparently doing very much of anything to add value to the process.

The White House Office of Management and Budget, the Congressional Budget Office, and even Denali's Inspector General have all suggested cutting the agency to save taxpayers money. The Delta Regional Authority consistently fails to meet even its own expectations, and has been cited by the Government Accountability Office for failing to report where its funds have gone.

March 16th, 3:05pm

Cart Before the Horse on Border Wall Spending

Mr. Peno Nieto, Build That Wall! (With apologies to Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev)

The Fiscal Year 2017 Supplemental Appropriation request for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is a cool $3 billion. That's less than one-tenth of the total supplemental request but is still a considerable increase for a department with a typical (2).png) budget of roughly $40 billion. Put another way, $3 billion may be loose change in the couch cushions at the Pentagon, but it's real money at DHS.

budget of roughly $40 billion. Put another way, $3 billion may be loose change in the couch cushions at the Pentagon, but it's real money at DHS.

And of that $3 billion, just a hair under half of it is for "The Wall." Specifically, "$1.4 billion for CBP [Customs and Border Protection] Procurement, Construction, and Improvements, including $999 million for planning, design, and construction of the first installment of the border wall, $179 million for access roads, gates, and other tactical infrastructure projects, and $200 million for border security technology deployments."

At TCS we've written a lot about the folly of the CBP wish-list of technologies that have not been properly used or maintained in the past. But it's galling to think of $1.4 billion of your tax dollars being spent for a wall that the President has consistently stated will be paid for by the Government of Mexico. And this supplemental request was made prior to DHS beginning the evaluation process on the contract proposals from construction companies bidding on the project.

Huh? How does DHS know enough to start paying for a wall when a design for that wall has not yet been approved? This is the cart before the horse and after several failed projects to secure and militarize our southern border, this seems to be a cart and a horse going the wrong way on a one-way street.

Time to stop, take a deep breath, and wait for the right time to start spending money on a wall that hasn't been designed.

March 16th, 2:40pm

Give Me the Cash; You Find the Cuts

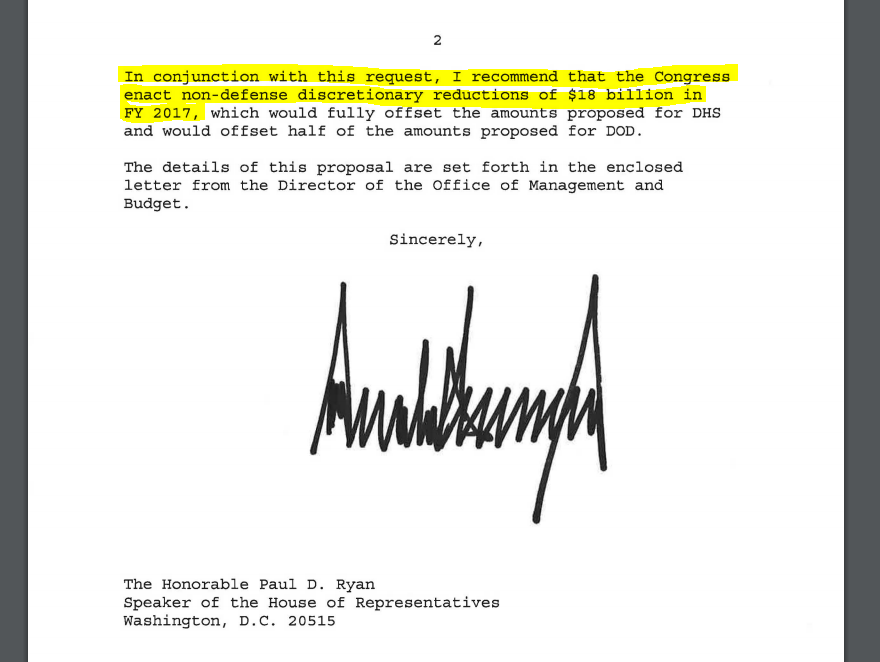

The FY17 Supplemental details $33 billion in increased defense and DHS spending, including nearly $1.2 billion for border wall. It partially offsets this increase by an $18 billion cut to non-defense discretionary spending. Remembering that the government is nearly half-way through the fiscal year, that will have double the impact and be doubly hard to find in the budget. That's why the Trump Administration didn't. Near the end of the letter the President sent to accompany the request he wrote:

In other words, Congress give us the cash and you find the cuts.

March 16th, 2:35pm

Possible New Tactic to Thin Agriculture Spending

The President's budget request seeks a $4.7 billion reduction in spending on Department of Agriculture discretionary programs. One of the bullets included in the summary indicates some amount of savings will come because the budget "Reduces staffing in USDA's Service Center Agencies to streamline county office operations, reflect reduced Rural Development workload, and encourage private sector conservation planning."(2).png)

USDA "service center agencies" covers a wide range of potential staff and functions. These offices deliver and manage everything from farm income subsidy programs, to conservation programs, to rural development initiatives. While we will have to wait to see specifics, this may be some well-worn territory.

The Farm Service Agency alone has around 2,000 local and regional offices, often serving one county. For decades administrations spanning Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama, have proposed – and TCS has supported reducing the number of FSA offices, with little impact. President Bush proposed eliminating as many as 700 offices in his 2008 budget request. President Obama's 2015 budget request proposed closing or consolidating 250 offices where there were either only one or in fact zero employees. And for decades, members of Congress representing rural areas have fiercely opposed these efforts. Now in annual appropriations Congress repeatedly prohibits any USDA funding from being used to close an agency office or to "permanently relocate county based employees that would result in an office with two or fewer employees without prior notification and approval of the Committees on Appropriations of both Houses of Congress."

So if you can't close an office, perhaps you just don't staff it? We'll have to see. But both Democrats and Republicans on the Agriculture Committees are already rallying against any reductions as they seek to increase federal spending in a new farm bill.

March 16th, 2:30pm

Mum on the Coast Guard

.png)

Leading up to the budget release, there were news reports about increased funding for Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the border wall possibly paid for in part with a $1.3 billion cut to the Coast Guard (roughly $9 billion annual budget). In what could oddly be a win for the Coast Guard, they are not even mentioned in the document one way or another. We'll have to wait until May to find out if the nation's oldest continuous sea-going service receives a cut

March 16th, 2:20pm

Skinny Budget Doesn't Put FY17 Budget Supplemental on a Diet

Alongside the FY18 "skinny budget", there is also the Fiscal Year 2017 supplemental request for the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security.

And while the skinny budget is positively anorexic when it comes to actual details, the FY17 supplemental is fat enough to require a trip to the gym. Altogether, this supplemental request would add $33 billion to the national debt broken down like this:

| Department/Account | Request (in $ thousands) |

|---|---|

| Defense/base budget | $24,900,000 |

| Defense/Overseas Contingency Operations | $5,100,000 |

| Homeland Security | $3,000,000 |

| Total | $33,000,000 |

Careful readers will notice that roughly 1/6th of the additional funds for the Pentagon would be in the "off budget" Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account. This means that $5 billion doesn't count against the caps in place under the Budget Control Act of 2011, as amended. And while we would prefer for OCO to fade away, we do find this request more defensible than ones recently offered by the Obama Administration. Of the $5 billion there are no accounts that jump out at us as being clearly a base budget requirement that is conveniently tucked into the off budget account. Instead, the OCO account is split up across four different funds that all have direct overseas responsibilities. We'd like to know more about this so-called "flexible fund" of $2 billion to defeat ISIS. Like the "European Reassurance Initiative" that came before it, this fund seems hasty and ill-defined at this point.

We'll be looking for more details. Meanwhile, here is the basic OCO breakdown as presented by OMB:

| Account | Request (in $ thousands) |

|---|---|

| Defeat ISIS | $1,400,000 |

| "Flexible fund" to defeat ISIS | $2,000,000 |

| Counter-ISIS (train & equip) | $626,000 |

| Ongoing Afghanistan operations | $1,100,000 |

| Total | $5,126,000 |

The request for the Pentagon "base budget" for things other than current overseas operations, is just under $25 billion and is broken down this way:

| Account | Request (in $ thousands) |

|---|---|

| Military personnel | $977,000 |

| O&M (including cyber and intel) | $7,200,000 |

| Procurement and Modernization | $13,500,000 |

| Research and Development | $2,100,000 |

| Supply stocks, facility repair, revolving funds | $962,000 |

| Military Construction | $236,000 |

| Total | $24,975,000 |

Close to 55% of the base budget request is for "procurement and modernization." This is in keeping with President Trump's frequent assertion that the military has been allowed to atrophy in the last 8 years. At TCS we would disagree that a Pentagon budget that ranged from a high of $691 billion to a "low" of $560 billion during the Obama Administration was not enough to meet the strategy, but we'll let that go for purposes of this discussion.

The $13.5 billion for procurement and modernization is thinly explained by calling out the following procurement programs for increases: Apache and Blackhawk helicopters, F-35 and F/A-18 aircraft, tactical missiles, unmanned aircraft systems, Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD), and the completion of one Arleigh Burke-class destroyer. Specific dollar figures for these programs are not revealed but we can glean some details from one of the tables provided at the back of the OMB submission. Here is our rendition of that table:

| Program/Service | Request (in $ thousands) |

|---|---|

| Aircraft, Army | $1,625,743 |

| Missile, Army | $852,654 |

| Weapons and Tracked Combat Vehicles, Army | $750,518 |

| Ammunition, Army | $486,685 |

| Other, Army | $449,345 |

| Aircraft, Navy | $4,006,977 |

| Weapons, Navy | $171,500 |

| Ammunition, Navy and Marine Corps | $53,100 |

| Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy | $691,020 |

| Other, Navy | $217,989 |

| Procurement, Marine Corps | $405,933 |

| Aircraft, Air Force | $1,847,520 |

| Space, Air Force | $19,900 |

| Ammunition, Air Force | $70,000 |

| Other, Air Force | $1,277,145 |

| Procurement, Defense-wide | $409,028 |

| Chemical Agents and Munitions Destruction | $127,000 |

| Total | $13,462,057 |

Careful reading of the table suggests the Army will spend about $1.6 billion for additional Apaches and Blackhawks. The Navy will spend just over $4 billion on F-35s and Super Hornets. (It is, however, impossible to tell if the F-35s will be for the Navy or the Marines since the Navy aircraft budget pays for both.)

The Air Force will probably spend $1.8 billion on additional F-35s although some unmanned aircraft spending comes in the aircraft spending line and some in the "other" line, so it's possible that $1.8 billion covers more than just F-35s.

And the DDG-51 destroyer will cost the Navy just under $700 billion in this supplemental request.

We'd like to give you more details but, unfortunately, we'd be guessing based on the amount of information that is currently publicly available. We'll keep "refreshing" the Pentagon Comptroller website and looking for all the details on both this FY17 supplemental request and the "skinny" budget request for FY18.

March 16th, 1:50pm

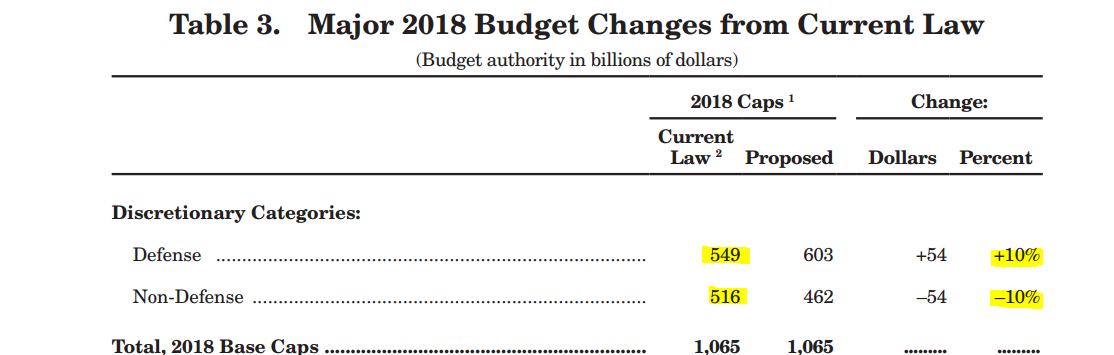

Billions of Dollars in Rounding Errors

Substantially changes FY2018 discretionary budget caps. Increases Defense cap $54 billion (9.8%) by reducing non-defense discretionary an equal dollar amount. But non-defense discretionary is already lower than defense spending so the $54 billion cut represents (10.5%)

The budget says there's a 10% increase in defense spending paid for with a 10% reduction in non-defense discretionary. But that's only if you look at rounding.

A true 10% cut would be $2.4 billion less than what is occurring. (More than the $2 billion in supplemental FY17 funding requested for a new flexible fund to counter-ISIS)

A true 10% increase in defense spending would require $900 million more. (More than the entire budget request for the Small Business Administration)

March 16th, 1:45pm

TCS Statment on the FY2018 Budget

It's hard to comment on a budget that has so little details and little budget context. This is the President's initial budget foray, the "skinny" budget, but this budget is more emaciated and starving for details than previous ones. This budget weighs in at 62 pages, less than half of President Obama's (140 pages) and barely a third of President Bush's (175) skinny budget. But it's not the number of pages but the numbers on the pages that matter in budgeting. There's no information about revenue or mandatory programs. Even if the budget offsets increased spending with cuts elsewhere, without the context of revenue and non-discretionary spending, there's no way of knowing if the deficit is growing or contracting. Without long-term projections on spending, there's no way to know what the debt will be in five years time.

We recognized Office of Management and Budget Director Mulvaney probably hasn't even had the time to unpack his office. This budget gives some context to what direction the Trump Administration wants to lead, but doesn't give Congress the direction it needs to legislate. We look forward to May when we will hopefully have details about the Fiscal Year 2018 budget.

March 16th, 1:30pm

President Trump's 'Skinny' Budget Is Live!

Marking his first budget request – a statement of vision for the federal government – the President has released his FY2018 budget.

America First – A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again

You can find TCS work on the President's budgets in previous years here:

– TCS Analysis of President's FY2017 Budget

– TCS Analysis of President's FY2016 Budget

– TCS Analysis of President's FY2015 Budget

– TCS Analysis of the FY2014 Presidential Budget Request

– TCS Analysis of the FY2013 Presidential Budget Request

– TCS Analysis of the FY2012 Budget Proposal

– TCS Analysis of the FY2011 Budget Proposal

Related Posts

Most Read

Recent Content

Our Take

Mar 3, 2026 | 4 min readOur Take

Mar 3, 2026 | 6 min read

Stay up to date on our work.

Sign up for our newsletter.

"*" indicates required fields

.PNG)

.png)

.PNG)